HOME | DD

FloydM127 — For Want of a Ship: No Seattle

FloydM127 — For Want of a Ship: No Seattle

#washington #alternatehistory #history #maps #nativeamerican #seattle #mapsandflags

Published: 2024-02-29 22:43:21 +0000 UTC; Views: 6780; Favourites: 80; Downloads: 9

Redirect to original

Description

For Want of a Ship

In late 1855, general warfare broke out between Whites and Natives throughout Washington and Oregon territories. That Summer, two Yakama women were raped and murdered by Oregonian miners, a crime had been repeated tens of thousands of times in the inexorable Westward march of the American and British Empires. In this time, it added to a number of grievances collected in the previous five years, including several intensive attempts at treaty-making from 1854-55, and provoked a revolt.

Among the native peoples of the region, there were mixed feelings about the expansion of American settlement, which began to turn hostile in the 1850s and settlement North of the Columbia increased. One such doubtful man was Kamiakin of the Mámachatpam Yakama, who upon meeting with George McClellan in 1852 was dully unimpressed with American intentions. Following the death of the Yakama women, there was a general agitation, made worse by the anti-American preaching of the Wanapum Yakama prophet Smoxalla, and opposition to the treaties made at the Walla Walla council in 1854. When Andrew Bolan, an agent of Indian Bureau was sent to observe the area, he was quickly killed, allegedly shouting “Do not kill me! I did not come to fight you” in Chinuk Wawa, the jargon language of the Pacific Northwest.

Following Bollens murder on September 20th, events unfolded quickly. Several columns were sent from the Dalles fort in Oregon, and Governor Stephens ordered the creation of militia companies to ‘Exterminate any hostile Indians.’ The initial American force, led by Colonel Granville Haller was encircled and forced to retreat to the Dalles by a Yakama force led by Kamiakin and Owhi, another influential Yakama. A larger force, led by Major Gabriel Rains returned to the region and forced Kamiakin to retreat at Union Gap on November 10th. Still, most of ‘Yakama country’ (bounded by the Columbia, Lake Chelan, and the Cascades range) was under hostile control, with only Fort Simcoe (named for the Símkoeħlama Yakama) as a bastion of American control. When Rain’s force entered the Catholic St. Joseph Mission along the Yakima River, they discovered a peace missive from Kamiakin, explaining the reasons for the rebellion, and ending with:

“If the soldiers and the Americans [settlers] after having read the letter and taken knowledge of the motives which bring us to fight, want to retire or treat [us in a] friendly [manner], we will consent to put [our] arms down and to grant you a piece of land in every tribe [as long as you] do not force us to be exiled from our native country, otherwise we are decided to be cut to pieces and if we lose, the men who keep the camp in which are the wives and children will kill them rather than see them fall into the hands of the Americans to make them their toys. For we have heart and respect ourselves. Write this to the soldiers and the Americans and they [may] give you an answer to know what they think. If they do not answer it is because they want war; we will then [get] 1050 men assembled. Some only will go to battle, but as soon as the war is started the news will spread along all our nations and in a few days we will be more than 10,000. If peace is wanted, we will consent to it, but it must be written to us so we may know about it.”

Outraged, the soldiers ransacked and burned the mission, assuming the Catholics would naturally be sympathetic to the natives[1].

November and December of 1855 saw the war expand in both directions. To the West, in the Puget Sound regions, natives with connections to the Yakama rose up, engaging in skirmishes along the White River that killed several settlers and volunteers in the region. To the East, Oregonian forces from the Dalles marched into Walla Walla territory to confront them, still wary of the Cayuse War a decade prior. They met with Peopeomoxmox, an influential man among the Walla Walla, who carried a white flag and asked to be peaceable. He and his party were arrested by the soldiers, and were shot, scalped, and mutilated by them when other Walla Wallas attempted to free them [2]. This action pulled the Walla Walla, Cayuse, and eventually other interior tribes into the war, now faced directly by the genocidal goals of the settlers.

In December, the Puget Sound natives, aided by Yakama and Klickitat forces, planned further and more audacious campaigns. On December 3rd, Lieutenant William Slaughter, who had fought in the White river skirmishes and the battle of Union Gap was killed by a Klickitat sniper, briefly throwing American forces in disarray. The Native forces, led by Klickitat leader Kaneset and Nisqually leader Leschi began to plan and organize an attack on the small town of Seattle, founded in 1851 and named for the influential Chief Seattle of the Duwamish in 1853. At the time, the settlement was small, holding less than 100 people and a single blockhouse. Governor Stephen’s was in the process of returning to the Puget Sound from West of the Rockies, and delivered a series of contradictory orders, including for the ship Decatur.

The USS Decatur was a small sloop, commissioned in 1839, that saw action in the Mexican-American War and in anti-slave trade operations in the Atlantic Ocean. In 1855, it was sent to Puget Sound via the strait of Magellan and Hawaii, but on December 7th it was grounded on a reef on Bainbridge Island. Unable to right the ship, the officers on board took small boats and canoes to Fort Steilacoom [2]. The loss of the Decatur limited American firepower in the sound, and left Seattle and New York – Alki vulnerable. This came to a head in late January of 1856, when native confederation forces converged on Seattle.

On the night of January 26th, the battle began, as some fifty Seattleites and two dozen settlers from the White River were besieged by a number of attackers. While reports of the size of the party ranged from 500 to 2000, its likely that no more than 200-250 at most actually participated. The settlers withdrew to the blockhouse in the middle of town, where they for several hours fought off the natives. Around midnight, the blockhouse caught fire, and the settlers were forced to flee, with many being killed and a few escaping via boat to Alki. In the end, sixty-five were killed and another ten injured, by far the worst tally of any engagement thus far in the war. Confederation casualties were light, likely no more than a dozen total. News of the battle ignited a new frenzy throughout the territory.

Worsening of the Western Campaign

The destruction of Seattle and increased harrying of American forts along the Green and Duwamish rivers shifted the tide of the war. For one, it wreaked havoc on an already unstable political climate in Olympia. Governor Stephens had returned in December, and immediately clashed with General John E. Wool, who had been controlling operations. Wool, a veteran of the War of 1812, displacement of the Southeast Native peoples, and Mexican-American war, was wary of the inflammatory actions of the settler militias in the region, and instructed his regulars not to aid volunteers and to protect the natives from them if necessary. Wool publicly criticized Stephens, and Governor George Curry of Oregon, for escalating a minor dispute into a major conflict. Wool’s strategy was to isolate native forces by constructing defensive blockhouses around key strategic areas in a slow fashion. However, after the battle of Seattle, Stephens ‘war of extermination’ policy won out, advocating for elimination and removal of all natives West of the Cascades. This resulted in more violence driving more previously neutral peoples into the arms of the Confederation.

When his friend Doc Maynard was killed in Seattle, the towns namesake, and Chief of the Duwamish (his name was historically pronounced siʔatɬ’) was 69. He had seen his people’s reduction during the epidemics of the 30s and 40s, and the movement of White settlers into his lands in the 50s. In 1848, he was baptized Catholic as Noah, although by 1856 even Catholicism was on the retreat in Washington, with Bishop Blanchet of Nisqually being withdrawn from the area. Despite once having strong influence in the region, including launching a genocidal campaign against the Aqokúlo at the mouth of the Hood Canal in 1847, by the 1850s he had lost much of his former power and influence. Hearing of the death of his friend and the deepening of the war, he took off to Olympia by canoe to make peace, where he was swiftly arrested, tried, and executed in February by the enraged settlers. New of his death filtered back to Duwamish and Suquamish lands, where it roused further rebellion in those regions, and prompted the burning and looting of the wreck of the Decatur later that month.

Another change was the shifting allegiance of chief Patkanim of the Snoqualmie. Patkanim, who in 1850 had been jailed at Alcatraz following an abortive raid on fort Nisqually[3], was initially a reluctant ally to the Whites, agreeing to allow the construction of a fort at the crucial Snoqualmie pass, one of the main connection points between Puget Sound and the interior. Doing so would have cut off Kamiakin’s forces from moving back and forth and would greatly strengthen American positions in the sound. Following the battle, and his chief rival Seattle’s execution, Patkanim remained neutral, and allowed Confederation forces to access the pass.

In March, Stephens was further wanting for a victory; despite successful raids on Skokomish and Chehalis villages, the settlers were panicked, and Ft. Nisqually and Steilacoom were full of scared refugees from the countryside. At the same time, the White Salmon River saw its own series of massacres by Yakama and Klickitat soldiers, and the East was in a worse state. In this climate, he was pushed to declare martial law, fearful of the French (bad), mixed-race (worse), Whig-voting (wort of all) settlers in Thurston and Pierce counties. These men, mostly former trappers and HBC workers were rounded up and imprisoned at Ft. Steilacoom, to the objections of General Wool and many settlers in the colony. Judge Edward Lander of the territorial supreme court set off by canoe to Olympia to challenge the ruling when he too was imprisoned [4]. Through March and April, this deepened the crisis further, resulting in a violent confrontation between French Canadians and American volunteers, and the further denigration of order in the Sound. It was in this climate of violence that the next stage of the war began.

“Boadicea of the Nesqually”

As Kamiakin’s Yakama aligned with the Cascades and Klickitat to raid settlements around the Columbia, and Smoxalla’s new religious movement among the Wanapum made ground in the East, one of Seattle’s children began a new movement. Kikisomlo, (also called Kikisoblu, /m/ and /b/ are allophonic in Lushootseed), one of Seattle’s several daughters, managed to become a symbolic leader of the Western forces. Alongside Leschi and Kitsap (of the Muckleshoot, a different Kitsap is the namesake of the Kitsap peninsula), she reorganized the force that attacked Seattle and planned further raids on Tacoma and Ft. Steilacoom. The initial settlement of Tacoma was abandoned following raids, and the party moved on to the key Ft. Nisqually, where in late April they fought a surprise raid, causing a dozen casualties among the volunteer companies there. Pushed back, they continued intermittent raids on blockhouses and forts in the area for the next several months.

Two events furthered the stage of the conflict during 1856. The Klallam people were brought into the war in late October, when the USS Massachusetts, a gunboat sent to replace the Decatur and aid in the war effort, bombarded a native potlatch ceremony near Port Townsend, which would be followed up over the course of the year on further raids and counterraids near Forts Dungeness and Ludlow. In November, the same ship destroyed a Haida and Tlingit raiding party off the coast of Whidbey Island, killing several dozen and depositing the rest in British Columbia. These distractions, along with continued conflict between Wool and Stephens allowed Kikisomlo to continue her presence throughout Puget Sound. Her next move would be the result of another American blunder.

Embarrassed by being forced to release the prisoners he held and threatened with removal from office because of the skirmishes between settlers in his territory, Governor Stephens wanted a major success. Going back across the Cascades, he called a second Walla Walla council, to continue the failed efforts he began in 1854-55. However, the situation of Winter 1856 was different than the one of 1854, and there were far fewer friendly people East of the Cascades. As he returned from his talks, his party was ambushed by hostile Walla Walla and Yakamas, and Stephens was killed [5]. This created a further power vacuum in the West and East. Learning of his death in December, Kikisomlo planned a new and bigger assault for the spring. Washington territory was a long way from D.C, and was made difficult to govern. As a result, it took almost six months for a replacement for Stephens to actually arrive in the territory, and in the meantime the Army and the militias rule. Clashes between volunteers, regulars, and indignant freed French settlers created a disorganized enough climate to allow Kikisomlo’s forces to successfully harry many of the forts between the Nisqually and Snohomish rivers, frustrating Wool’s strategy.

Battle of Olympia

By early 1857, the situation in the Puget Sound region had disintegrated. Aside from a few score forts, most of which were single blockhouses, everywhere north of Olympia was out of government control. The Areas of Willapa bay and Gray’s Harbor, with lower and more peaceable native populations and a stream of settlement in costal communities, was less violent, seeing only small skirmishes and clashes, but the Northern Olympic peninsula and Eastern region of the Sound were in uproar. Increased troop compliments spent more time handling raucous settlers and militias than fighting Kikisomlo’s forces. As part of their strategy, she and Leschi required that all White settlements in the Puget Sound be evacuated, and as such they attempted an audacious attack on Olympia. This was a far larger settlement than Seattle, and with only a limited number of soldiers and guns, it was a difficult prospect, but considering the increasingly desperate situation of the Confederation vis à vis American forces, the battle was forced.

The Battle of Olympia, fought from 2-5 February 1857, marked the end of active resistance in the Puget Sound area. As many as five hundred natives raided the town on February 2nd, burning it and overwhelming the small garrison. The next day, regular soldiers arrived from Fort Steilacoom and the surrounding blockhouses, routing the Confederation forces and pushing them back into the forests. The natives were rounded up over the next two weeks, and either killed (if by volunteers) or evicted East of the Cascades (if by regulars), with over 200 confirmed casualties and more suspected. Kikisomlo herself disappeared, and despite various urban legends and myths was considered killed. The corpses of several native women, likely killed by settlers, appeared periodically over the next few years supposedly bearing her name. By May of 1857, Wool declared that the War in the Sound was finished, although resistance would continue for the next year.

Defeat and Aftermath

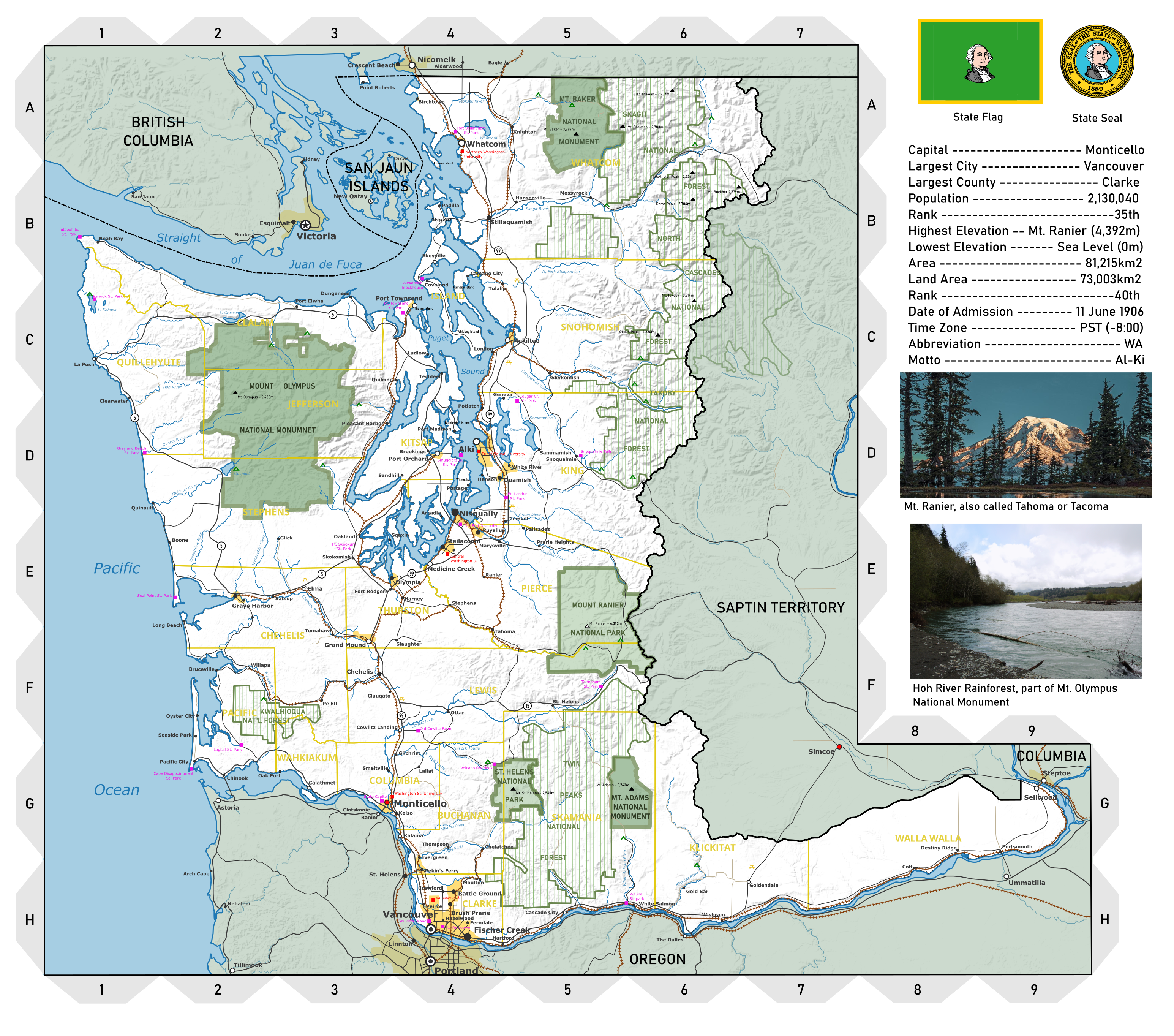

In the end, the forces of the Confederation were defeated. From 1857-1859 most natives of Puget Sound were removed to East of the Cascades, where Kotaiken’s Three Flag Army and the forces of the Cour d’Alenes and Nez Perces continued to fight the federal government. Olympia was rebuilt, and towns around the Puyallup and Duwamish resettled, although the territorial government was moved to Vancouver, and later to Monticello at the mouth of the Cowlitz river. For the natives, it was just another war eventually lost, followed by forced resettlement and cultural genocide, as had been done hundreds of times over past three centuries. For the government, it was further proof that regions of settlement should be created exclusively for white and native settlement and led to the continued barring of settlement East of the Cascades for another decade. And of course, there were other effects.

In 1859, British and Americans faced off over the disputed San Juan Islands, claimed by both as a result of poor surveying and overly-ambitious boundary-making. But in this case, the Americans were rather unwilling to negotiate. They had since 1855 accused British Columbia of providing aid and refuge for Confederation militants, worsened by Kamiakin and Leschi’s fleeing to the province after the Confederation collapsed. The American soldiers were veterans of the siege and destruction of Qatáy, the pacification of the Hoh river, and the short war against Patkanim and the Snoqualmie in 1858-59. They had seen the Governor of BC be relatively peaceable to the Natives, and accept with open arms the mixed-race former HBC employees that had fled Washington and Oregon. They were deeply distrustful of British and Anglo-Canadian motives. And so when accusations were brought over dead pigs and other minor grievances, they were much more ready to shoot.

When the British Empire went to war with the United States in 1861, in part citing the minor armed conflict in the San Juans and around British Columbia, the War in the Puget Sound came once again into the public consciousness. Stories, perhaps spread by BC Governor James Douglas, moved the British public with stories of the ‘noble savages’ of the Puget Sound who were ‘brutally and bloodily suppressed’ by the Americans. British newsmen and authors noted the similarities between Kikisomlo and the romantic Celtic figure Bouddica, whose tale of tragic resistance to Roman occupation had become a cultural icon during the Victorian era. As British soldiers reoccupied ft. Vancouver and bombarded San Francisco in 1862, the British and Canadian presses featured tales of the ‘Boadicea of the Nesquallies” who fought and died valiantly for freedom against American oppression (that the colonial governments in BC treated natives similarly, and that the British were fighting for the independence of a slavoctaric state in the American South were unheeded).

In the modern day, the story of Kikisomlo continues to be said. In Washington state, she is mentioned only in textbooks as a savage who ordered the deaths of hundreds of American men, women, and children. In the plurality-native Saptin territory, she is one of many heroes who kept the dream of sovereignty alive. In British Columbia and Canada as a whole, she is another of the many figures who fought against the Americans. In Libertania and the other petty states that fell out of the old CSA in the 1880s, she is a revolutionary, who supposedly was killed for her belief in racial and gender equality. But she is perhaps most revered and remembered in the crown colony of the San Juan Islands, an accident of geography and semi-sovereign state populated by Anglo-Canadians, Hawaiian Kanaka laborers from Cowlitz farms, and the scattered remains of the Puget Sound native peoples who were not moved across the Cascades. There, at Cattle Point on San Juan Island, looking south to a state where officially no natives live, there is a statue and plaque, presenting an overdramatized visage of Kikisomlo, and an except from a speech attributed at times to her or her father, but likely made by neither:

“And when the last Red Man shall have perished, and the memory of my tribe shall have become a myth among the White Men, these shores will swarm with the invisible dead of my tribe, and when your children’s children think themselves alone in the field, the store, the shop, upon the highway, or in the silence of the pathless woods, they will not be alone.”

[1]: This is a common theme in the history of the Pacific Northwest (and 19th century America as whole), where Catholics are seen as a fifth column.

[2]: The POD: OTL the Decatur was grounded but was able to free itself in time to defend Seattle during the battle.

[3]: OTL he aligned with the Americans partially for this reason, as well as his long-term rivalry with Chief Seattle and the Duwamish. In this TL, both reasons are mitigated.

[4]: This all really happened, and a militia raised to free Lander almost came to blows with Stephen’s militias; in this climate, increased fear as a result of Seattle leads to a shootout.

[5]: This also happened OTL, although Stephens was able to escape without injury.