HOME | DD

Irrsch — Hejkals - 3rd Trophic Level Carnivorous Parrots

Irrsch — Hejkals - 3rd Trophic Level Carnivorous Parrots

#bird #flightless #parrot #flightlessbird #specevo #parakeet #parrots #speculativeevolution #speculativebiology #speculativezoology

Published: 2023-01-13 22:31:29 +0000 UTC; Views: 909; Favourites: 8; Downloads: 0

Redirect to original

Description

From the logbook of the first expedition to Maria Theresia Land as written by Petr August Hyřman z Brychtu, 1843 (translated from Czech):

The 6-8th of June 1843

The Mainland isn't large, but the tussock plain appears to be limitless. We are taking our time while crossing it, taking samples and using our telescopes to observe various animals. They seem skittish and it is hard to come close, especially in this open grassland, but close to waterholes and along rivers tracks are abundant. I found observations are easier on solitary ventures. Sůvas, Chůdonohs, Cepínozobs - I was able to observe them from very close distances and could have shot one or two if I wanted or if food was to be ensured. From a comfortable seat on a solitary tree, I also observed a small group of large parrots, green heads and brown-green bodies, I did not see them fly, they looked like able runners anyways. They first introduced themselves by long, flute-like calls, chattering among themselves. When one spotted me, it called in a long "heeeeeey" and the others shut up. Shortly after the rest of the group appeared from among the tussock-mounds, keeping their distance they chatted and chirped among themselves, changing positions to get a better look. I shall name them "Hejkals".

[...]

The 10th of June 1843

[...]

The Hejkals appeared again. They came close to the camp and came even closer when Brekken brought a Cepínozob and portioned for food. They were only sporadically visible, hid in the tussock, but appeared when Brekken threw some meat to them. He had some fun with them, he threw them some of the meet and they seemed excited.

[...]

The 10th of June 1843

[...]

Brekken befriended the Hejkals. One of them let itself be fed from hand and the rest joined swiftly. Brekkens intuition was right - they are carnivorous. he played with them for hours, in the end they even were so daring as to jump onto his shoulders, try to steal his knife and untie his shoe laces. They left only once Brekken screamed for one of them tried to nibble at his sleeve and bit him slightly. The cut is clean, like with a knife.

[...]

The 11th of June 1843

[...]

The Hejkals are a menace. While we slept, they bit holes into the tent, two baskets, they ate a part of our food and trashed the camp. We lost half of the second sketchbook to their curious destructivity, as well as some collected feathers, and part of the botanical collection is in disarray. They did so in utter silence, we would probably be eaten alive if one of them didn't threw our pot on itself. Brekken shot one to scare the others off - "Ullemule", as he called the specimen, shall be our dinner tomorrow. He is certain Ullemule is the one which bit him. From now on we are establishing guard duty.

[...]

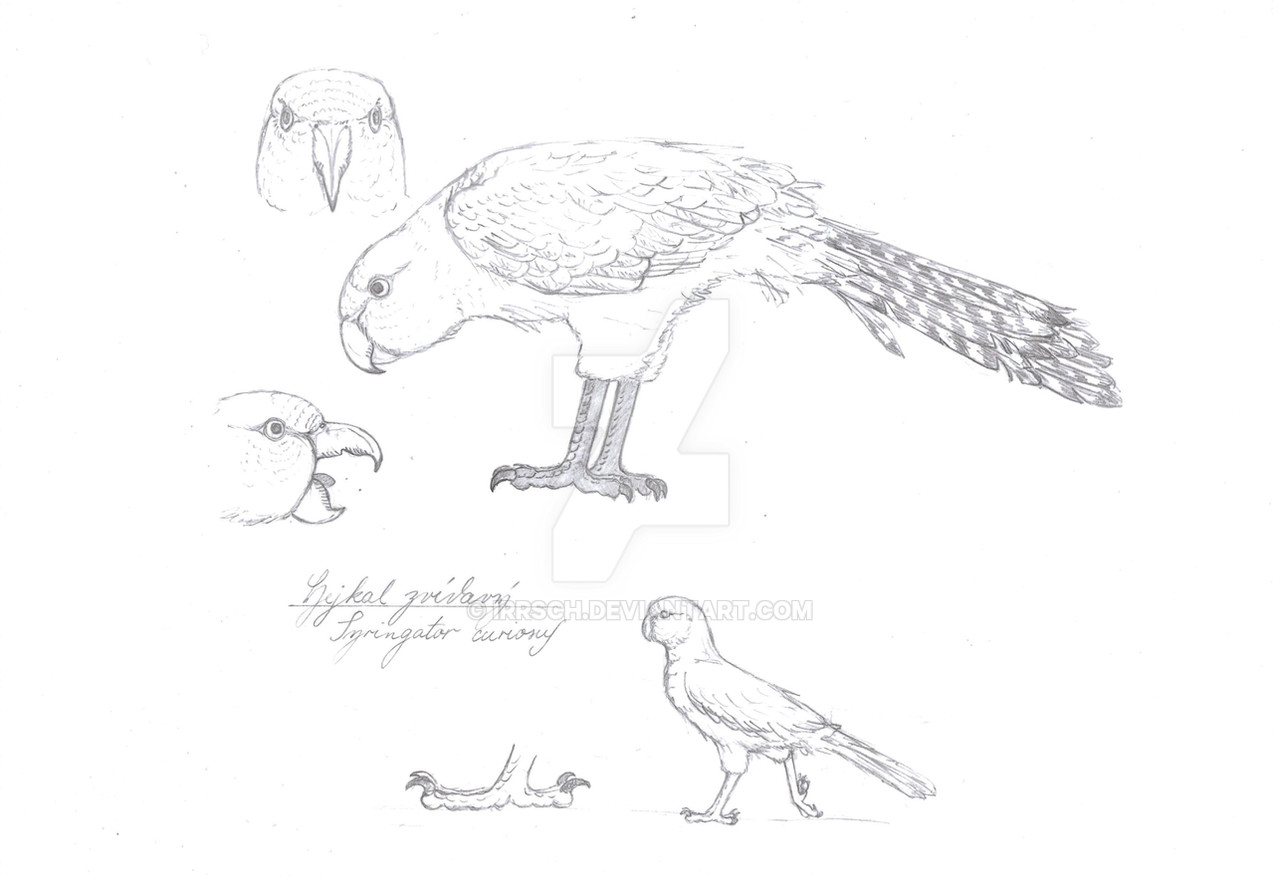

Hejkals (Syringator sp.) were large probably flightless parrots. Adults measured from 45 to 90 cm (23 to 25 in) in length, 34 to 50 cm in hight, and weight can vary from 1,5 to 6 kg at maturity. Males were larger than females. It is uncertain if Hejkals were capable of flight - having relatively short wings for their size and having very small keels on their breastbones (at least in comparison to other parrots – their keels and wings were certainly larger than in the only comparable extant parrot species, the Kākāpō (Strigops habroptilus) of New Zealand). Hyřman never described them as flying, stories from whalers however sometimes do. Their locomotion is described as a slow "promenading" and a "fast trot" during which they sometimes helped themselves with their wings. Some less credible stories describe them as “sweeping down” from trees or rocks onto their prey. Hejkals probably used their wings for balance and to break their fall when leaping from trees, but active flight is far less certain.

The backs and wings of Hejkals had light brown-green feathers barred or mottled with black, dark brownish grey and yellow feathers, whereas their bellies were moss-green to yellow with a similar mottling, blending well with the long blades of Tussock and other grasses and giving them an overall dark appearance. The downside of the wings was the same colour like the underparts but also has a "reddish gleam", whatever this is supposed to mean. In some specimen or populations, the breast and flank parts could be lighter, yellowish-green streaked with yellow. The belly and undertail faded from dark green to brown-green to dull red, which colour then dominated and saturated into bright red on the underside of the tail feathers, which were dark-to-moss-green with dark brown stripes on the upper side. The neck and head were predominantly green streaked with pale green and weakly mottled with brownish-grey, lightly barred, with some dull red on the forehead in some specimen. The feathers are described as being exceptionally soft, even the flight feathers on wings and tail are describes as "soft like in owls". The beak was of ivory colour with a dark grey or black tip, with its top being slightly darker. The upper jaw was hooked and narrower than usual in parrots and the lower jaw had a significantly “circular” back part – both upper and lower jaw had serrated edges and together they probably worked like scissors or a paper cutter. The eyes were hazel. The feet were large, scaly, dark gray in colour and, as in all parrots, zygodactyl. They possessed large claws which were in an erected position when walking or running.

It is unclear whether sexual dimorphism was responsible for slight variations (most notably red plumage on the faces), or not. Not enough observations were made to distinguish between females and males aside from their size. Unfortunately, Hyřman nor any of the later witnesses did correlate size with variation in coloration or other differing traits. Some differences in accounts can however be traced to different species (or subspecies) of Hejkals being described.

Hejkals had a variety of calls, a number of which was recorded by Hyřman. Aside from their notorious hééjs they supposedly also uttered kjú-kjú-kjú, káó and úhúk. Overall, he likened the tone of their call to barn owls or reed flutes. Hyřman also noted he often heard a loud series of hóhóhééé in the night and he hypothesised these were also calls of Hejkals, though this is not sure.

It is unclear whether Hejkals were nocturnal or diurnal. Most of Hyřmans observations suggest the later, however later stories describe them all as diurnal. Their eyes didn't seem particularly large, but this has only limited suggestive value in the matter. However keen eyesight is very likely as Hejkals were carnivorous and were active hunters. They lived and supposedly also hunted in pairs or groups of up to six birds - according to Hyřman they hunted even some of the larger species of birds on Maria Theresia Land like the Ryjozobs, however their main prey consisted most likely of smaller species. Hyřman describes their hunting technique as follows:

[...]When hunting smaller prey, Hejkals find it and kick it with their feet or step on it and bite it to death with their beaks like cutting with scissors. I also observed them hunting Ryjozobs and Cepínozob - the Ryjozobs fended them off, but the Cepínozob had poor luck. They chased it probably for some time, then they jumped on its back whilst flapping with their wings, causing their prey to lose its balance and fall. Before it could get up again, several others jumped in its back or flank to hold it down while another Hejkal or two advanced to its neck, held it down with their long legs and finally cut the Cepínozobs throat. It bled to death shortly after. [...]

Later stories of sheep herders describe their hunts as "devilish" - they supposedly jumped on the back of a sheep and held onto the animal’s wool, biting it all over its back, neck and ears or balancing down to bite it into its stomach, flapping with their wing and laughing "demonically". With every bite they supposedly caused deep and wide wounds like cookie cutters and their prey fell victim to blood loss. Suffice to say, these stories, regardless if true or not, only speeded up the extinction of the Hejkals. However, they seem likely, since if Hyřman was right and the main hunting method of Hejkals was to jump onto their preys back to cause it to fall to the ground and then to give it a killing blow, this technique probably did not work as well on four legged animals like sheep. The biting capabilities of their beaks also seem to fit the described "cut out wounds" well, as the serrated beaks seem to have been adapted to cause such damage.

It is unclear whether Hejkals actually coordinated their hunts or not - just as likely they just "hunted the same prey simultaneously" without actually separating roles during the hunt. It is just as unclear what structure their packs had, how they bred, how, where and when they nested, how many offspring they had and so on. Our knowledge about them is unfortunately very limited, the bulk of information comes from Hyřmans notes and the rest from fragmentary second-hand tales and stories from people who spoke with the few sheep herders of late 19th century Maria Theresia Land. They were certainly very curious and learned fast, and they learned swiftly to be cautious of humans with weapons or sticks in their hands and to avoid dogs and pigs. Hyřmans account describes them with a certain sociality, though the information is inconclusive.

Hejkals occupied all biomes of Maria Theresia Land; they could be found in forests, marshlands, high in the mountains above the tree line, but their main domain were the tussock grasslands. There were 3 species of Hejkal: The Mainland or Curious Hejkal (Syringator curiosus) and the smaller and far more enigmatic Skogsö Hejkal (Syringator jacksoni) and Forest Hejkal (Syringator silvestris), which differed from the Mainland Hejkal in colouration also. There might have been more species of Hejkal as the population on other islands might have been fairly distinct, but there is so far no way to prove this. Taxonomically their closest relatives were the Hejkáleks (Syringula sp.) and, more distantly, the Theresian Mountain Parakeet (Enicognathus montanus) and the Hunter Parakeet (Enicognathus venator), themselves closely related to south american parakeets of the same genus.

As mentioned, the encounters between Hejkals and sheep herders probably advanced their extinction: Hejkals were a keystone species, besides hunting they were also carrion eaters and filled a similar niche like foxes (they themselves were probably only hunted by Sůvas and maybe by some of the larger birds of prey of the archipelago) and their population must have been significantly hit by the sudden changes accompanying the environmental collapse of Maria Theresia Land. Even if they were somehow immune to rats predating on eggs and chicks and might have even benefited from rats or even cats as prey, their main prey species went extinct very fast. It is likely the stories about attacks on sheep and goats were symptomatic of a predator readapting itself to new (and abundant) prey - however with this change they also provoked the herders, who shot Hejkals on sight and lured them into traps. It is unclear when these birds actually went extinct, remnant populations might have survived in isolated valleys for decades after the last report, a conservative estimate would set the date to around 1870-1880.