HOME | DD

Paleonerd01 — Carcharocles auriculatus

Paleonerd01 — Carcharocles auriculatus

#evolution #megalodon #palaeontology #paleontology #carcharocles #obliquus #fossilsharkteeth #carcharoclesmegalodon #extinctshark #fossilshark #fossilsharktooth #sharkevolution #otodusmegalodon #lamnaobliqua #otodusotodusobliquus #otodustooth #otodusobliquustooth #carcharoclesaksuaticus #carcharoclesauriculatus #sizecomparison

Published: 2022-01-25 06:40:02 +0000 UTC; Views: 12497; Favourites: 124; Downloads: 21

Redirect to original

Description

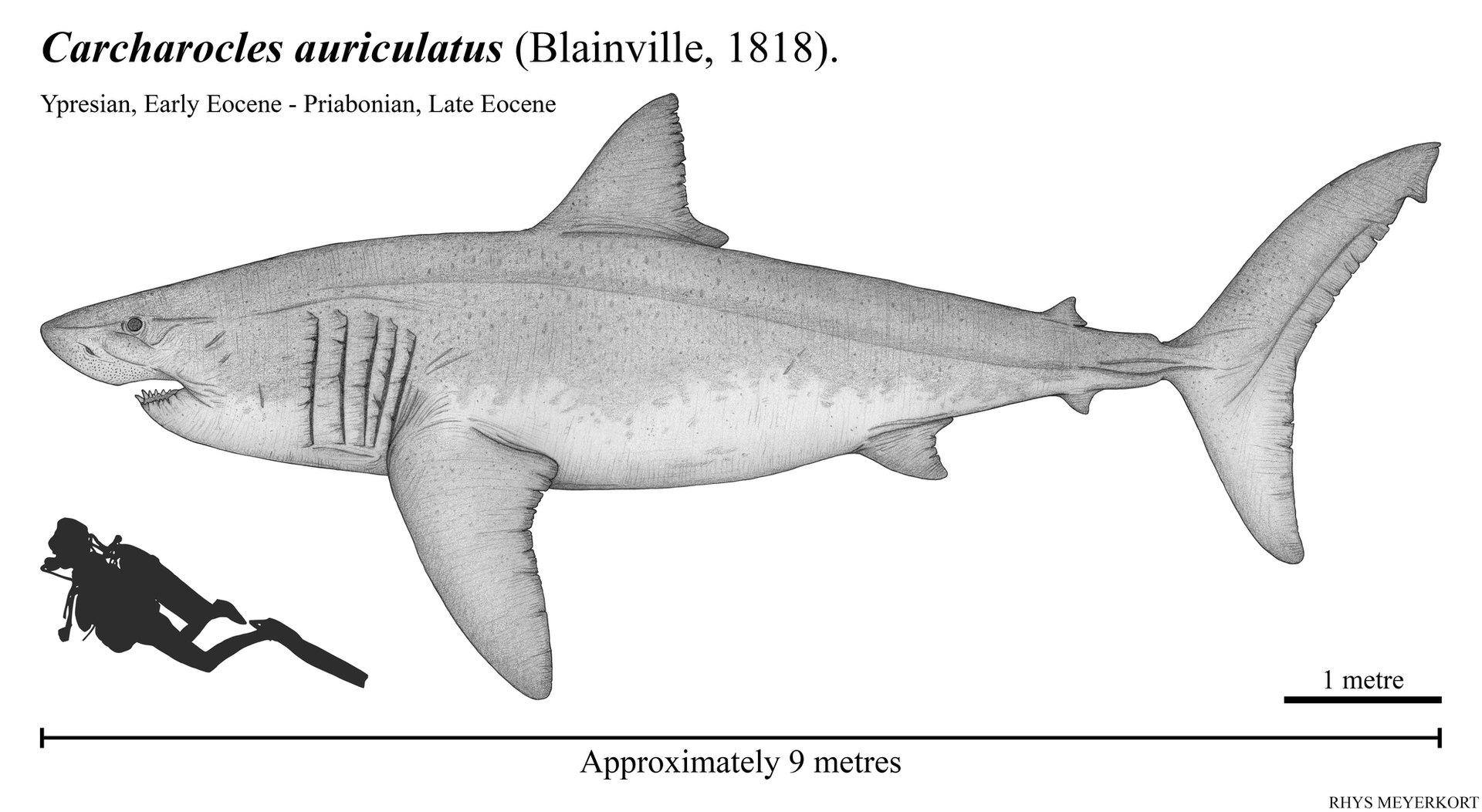

Carcharocles auriculatus was a large species of Lamiform shark in the Otodontid family, ancestral to the iconic C. megalodon. C. auriculatus teeth have been discovered in North America, the United Kingdom, Morocco, Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, South America and even Antartica. This chronospecies can be identified by the following characteristics, a triangular main cusp, straight anterior teeth, cutting edge with coarse, somewhat irregular serrations that diminish in size towards the apex of the crown, triangular divergent lateral cusplets with crenulated serrations, a convex lingual crown face, a flat labial crown face, a well-developed “V” shaped chevron scar on the lingual face, and a prominent lingual protuberance of the root.

C. auriculatus first appeared in the Ypresian stage of the early Eocene, and coexisted with the earlier Otodus obliquus and O. aksuaticus before eventually replacing them in the Lutetian and Bartonian stages of the middle Eocene. From a macroevolutionary perspective, it’s believed O. obliquus gave rise to O. aksuaticus through the acquisition of coarse, irregular serrations that do not continue towards the apex of the crown. Then, O. aksuaticus gave rise to C. auriculatus and the proceeding Carcharocles lineage. C. auriculatus was the first species in the Otodus-Carcharocles lineage to possess a fully serrated cutting edge.

Blainville (1818) originally assigned the name Squalus auriculatus to two teeth figured by Burtin (1784). These teeth were from the collection of A. Brongniart and were discovered in Belgium, most likely from either the Brussels Sand or Lede Sand Formation, dating to the Lutetian stage of the middle Eocene (Brignon, 2021). Blainville noted the triangular crown and serrated cutting edge but drew greater attention to the serrated lateral cusplets. Agassiz (1843) later erected the name Carcharodon auriculatus, likely due to the serrated triangular teeth superficially resembling those of the modern white shark (Carcharodon carcharias).

Wishing to distinguish the “mega-toothed” sharks from the modern white shark, Jordan & Hannibal (1923) erected the new genus Carcharocles and assigned C. auriculatus as the type species. Traditionally, unserrated teeth have been placed in the Otodus genus, while teeth with a fully serrated crown are assigned to Carcharocles. However, Zhelezko and Kozlov (1999) considered the presence or absence of serrations insufficient to distinguish different genera, so synonymized Carcharocles with Otodus. Because the Carcharocles species are likely directly descended from O. obliquus through anagenesis, some researchers have also chosen to synonymize Carcharocles with Otodus to maintain a monophyletic clade (Shimada et al., 2016).

Not all researchers agree, and this would only move the issue of paraphyly further back, as Otodus is almost certainly descended from Cretalamna, so to maintain a monophyletic clade Cretalamna would also need to be synonymized with Otodus. One solution proposed by Cappeta (2012) was to divide Otodus into several subgenera. These include, Otodus (Otodus) for unserrated teeth with lateral cusplets, Otodus (Carcharocles) for serrated teeth with lateral cusplets, and Otodus (Megaselachus) for serrated teeth without lateral cusplets. Another simpler solution is to accept Linnaean genera as inherently paraphyletic concepts and keep Carcharocles as the genus for serrated teeth.

The appearance of C. auriculatus in the Ypresian preceded the appearance of large marine Archaeocetes. Therefore, it is likely that the acquisition of serrations and the switch from a grasping tooth to cutting a tooth evolved first to feed on larger Teleost and Chondrichthyes prey and was only later adapted to feed on cetaceans in the late Eocene and Oligocene.

References:

Agassiz, L. (1843). “Recherches Sur Les Poissons Fossiles. (Tome III).” Imprimérie de Petitpierre.

Blainville, H. M. D. (1818). “Poissons fossiles.” Nouveau Dictionnaire d'Histoire Naturelle, 27: 310-391.

Brignon, A. (2021). “Historical and nomenclatural remarks on some megatoothed shark teeth (Elasmobranchii, Otodontidae) from the Cenozoic of New Jersey (U.S.A).” Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia, 127(3).

Burtin F.-X. (1784). “Oryctographie de Bruxelles, ou descrip- tion des fossiles tant naturels qu’accidentels découverts jusqu’à ce jour dans les environs de cette ville.” Imprimerie Le Maire, 153.

Cappetta, H. (1987). “Chondrichthyes II : Mesozoic and Cenozoic Elasmobranchii.” In: Schultze, H. P, (ed). “Handbook of paleoichthyology (Volume 3B).” Verlag Dr. Gustav Fischer, 1-193.

Cappetta, H. (2012). “Chondrichthyes. Mesozoic and Cenozoic Elasmobranchii: Teeth.” In: Schultze, H. P, (ed). “Handbook of paleoichthyology (Volume 3E).” Verlag Dr. Gustav Fischer, 512.

Ehret, D. J., Ebersole, J. (2014). “Occurrence of the megatoothed sharks (Lamniformes: Otodontidae) in Alabama, USA.” PeerJ, 2: e625–e625.

Jordan, D. S.,Hannibal, H. (1923). “Fossil sharks and rays of the Pacific slope of North America.” Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences, 23: 27-63.

Long, D. J. (1992). “Sharks from the La Meseta Formation (Eocene), Seymour Island, Antarctic Peninsula.” Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 12(1): 11-32.

Shimada, K., Chandler, R. E., Lam, O. L. T., Tanaka, T., Ward, D. J. (2016). “A new elusive otodontid shark (Lamniformes: Otodontidae) from the lower Miocene, and comments on the taxonomy of otodontid genera, including the 'megatoothed' clade.” Historical Biology, 29(5): 1-11.