HOME | DD

bagera3005 — Grumman TBF Avenger

by

bagera3005 — Grumman TBF Avenger

by

Published: 2011-04-19 08:18:09 +0000 UTC; Views: 27567; Favourites: 161; Downloads: 519

Redirect to original

Description

Grumman TBF AvengerThe Planes

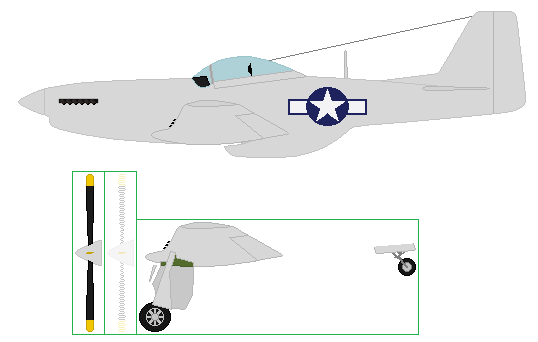

TBF Avenger in profile

Share9

While the Douglas Devastator had been "state of the art" when it was introduced in 1935, by 1939, the US Navy determined that it needed a more potent torpedo bomber, one with greater range, larger payload, faster speed, and tougher resistance to battle damage. The requirements for the new aircraft included: a top speed of 300 MPH, a (fully loaded) range of 1,000 miles, an internal weapons bay, 2000 lbs. payload, and a ceiling of 30,000 feet.

The Grumman "Iron Works" almost inevitably would be the supplier. Leroy Grumman, an engineer by background, helped design the torpedo bomber that would meet the navy's specs. The prototype was designated XTBF-1: eXperimental, Torpedo Bomber, F = Grumman, 1st variant. Two aircraft were built, one of which crashed in the woods near Brentwood, Long Island. But the program continued at the rapid pace which was a hallmark of Grumman's production.

Built around the 1700 horsepower Wright R-2600-8 engine, a 14-cylinder double row radial, the new TBF featured:

folding wings - critical for carrier use. Grumman developed a unique wing-folding mechanism for the TBF and F6F, which tucked the wings flat against the fuselage, for the most compact storage possible. Allegedly, Leroy Grumman first brainstormed the idea with a soap-eraser and paper clips.

three seats - A pilot, a rear gunner, and a bombardier/belly gunner.

powered rear turret - As required by the Navy, the plane included a powered turret for the rear gunner, originally equipped with a single .30 caliber machine gun.

three .30 caliber machine guns - The turret gun noted above. A nose-mounted gun for the pilot, firing through the propeller. And another rear-firing .30 caliber was tucked into its belly. This weaponry was increased in later variants.

large internal bay - By mounting the wings mid-way up the fuselage, Grumman allowed a roomy bay, for one 2,000 lb. torpedo, or four 500 lb. bombs, or an extra fuel tank.

large wings - A Grumman trademark. Relatively large wings helped to make Grumman aircraft easier to handle, a vital characteristic for a plane flown by masses of pilots with varying skill levels from pitching & heaving carrier decks.

extreme ruggedness - Another Grumman feature. The ability to absorb battle damage and still fly was equally important, especially to the aircrews.

On the afternoon of December 7, 1941, Grumman held a ceremony to open its new Plant 2 in Bethpage and display the new torpedo bomber to the public. During the program, Grumman vice president Clint Towl was called to the phone. "The Japs have bombed Pearl Harbor. We're at war." No announcement was made and the festivities continued. When the crowd filed out of the plant, they locked the gates, swept the plant for saboteurs, and went to a war footing, which they stayed on for almost four years.

Over the next few months, Grumman struggled mightily to turn their hand-crafted prototype into a mass-produced airplane. By June, the company had delivered 145 TBF-1's to the Navy, a pace that would be dwarfed in the next three years.

First Combat - Midway

Only six TBF's actually entered front-line, combat service in time for the critical Battle of Midway on June 4, 1942. These planes, attached to VT-8, flew up to Midway Island itself three days before. Commanded by Lieutenant Langdon K. Fieberling, none of the TBF pilots had ever been in combat, and only a few had ever flown out of sight of land before. (Most of this squadron, the famed Torpedo Squadron Eight, flew the outmoded Douglas Devastators from the carrier Hornet.) But both new and old were nearly wiped out.

Lieutenant Fieberling's six TBFs reached the Japanese fleet at 7:10 AM, dropped to low altitude and bore on toward the carriers. Zeros swarmed around the vulnerable torpedo planes. Two TBFs were destroyed in the first attack, followed by three more. Realizing that he could not reach the carriers, Ensign Albert K. Earnest loosed his torpedo at a cruiser, then broke away with two Zeros after him. Earnest flew his shot-up TBF back to Midway, navigating "by guess and by God." Earnest's was the only TBF to return, with nothing but the trim tab for longitudinal control, with one wheel and the torpedo bay doors hanging open. Radioman 3rd Class Harrier H. Ferrier was injured and Seaman 1st Class Jay D. Manning, who was operating the .50 caliber machine gun turret, was killed during the attack.

See picture

Eastern Solomons - Aug. 24, 1942

After the Americans took Guadalcanal, Admiral Yamamoto wasted no time in organizing a large naval counter-stroke. On the 24th of August, the opposing carrier forces met; this time the US Navy had just two carriers: Saratoga and Enterprise. By August, enough TBF's had been delivered and worked their way through the pipeline to equip the two ships' air groups with 24 TBF's:

VT-8 on "Sara," commanded by Cdr. Harold "Swede" Larsen

VT-3 on the "Big E," led by Lt. Cdr. Charles M. Jett

During this afternoon and evening, 26 Avengers were launched in four different strikes. On the second strike, the torpedos struck the light carrier Ryujo and helped to sink her. And ARM3/c C. L. Gibson, a TBF gunner, claimed a Val dive bomber. In exchange, seven Avengers were lost.

Santa Cruz - Oct. 26, 1942

In the war's fourth big carrier engagement, the Avengers didn't do much damage.

The two surviving carriers in the Pacific, Enterprise and Hornet, carried 14 Avengers each. In late October, the two U.S. flattops met the Japanese effort to seize Guadalcanal. The opposing fleets' patrol planes spotted each other in the early morning and both launched air strikes across the intervening 200 miles. Enterprise and Hornet sent out three strikes, totalling 73 planes: 18 Avengers, 32 dive bombers, and 23 F4F fighters.

Commanding Torpedo Ten, VT-10, from Enterprise was Lt. Cdr. John A. Collett. He led his torpedo bombers westward, toward the Japanese ships, passing Zeros and Vals heading for the American ships. When the U.S. planes found their targets, the Japanese combat air patrol and anti-aircraft knocked most of them down. The SBD's damaged on carrier, but the TBF's were shot out of the sky. A Zero shot up Lt. Cdr. Collett's Avenger. He and his radioman, ARM1/c Thomas C. Nelson were seen parachuting. Nelson was captured and (I believe) survived as a POW. Collett was never seen again. (A personal note - My maternal ancestors include the Abbott family of Winterport, Maine. The Abbott family cemetary there includes a stone inscribed "Lt. Cdr. John A. Collett, Commander VT-10, Lost at the Battle of Santa Cruz, Oct. 26, 1942." Of course, he isn't buried there. I presume that his mother was an Abbott, possibly indicated by his middle initial "A." One of my many unfinished projects is to determine Collett's relationship to my Abbott relatives. - SS)

These early battles showed the type's strengths and weaknesses. Perhaps its biggest weakness was not actually a problem with the aircraft itself, but rather with the deficient torpedoes used by the US Navy in the first two years of the war. The damn things just didn't explode (at least not with any high degree of reliability). The Mark 13 torpedoes were fragile, and had to be dropped from a low height, at speeds below 130 MPH. They under-ran their indicated depth by 11 feet; they failed to explode when they hit, and they sometimes blew up prematurely. Therefore the TBF's flew a lot of missions with ordinary 500 lb. bombs. The aircraft itself was sound and could be used in various roles: torpedo bomber, glide bomber, reconnaissance, mine-layer, and scout plane. With its good radio facilities, docile handling, long range, and extra seating, it made an ideal command aircraft for Air Group Commanders (CAGs).

Sink the Hiei - Guadalcanal

Navy and Marine Corps TBF's scored in a big way in November, 1942. Led by Lt. Col. Paul Moret, Marine Scout Bombing Squadron 131 (VMSB-131) flew TBF-1 Avengers from Guadalcanal during this pivotal month. They arrived on the 12th, just in time for the last big Japanese attack. Leading the powerful Japanese naval forces was the Hiei, a 37,000 ton battleship. Through the night of the 12th-13th the American and Japanese surface ships pounded each other, and the Japanese pulverized Henderson Field with 14-inch explosive shells, in the great naval Battle of Guadalcanal. The US Navy lost 2 cruisers and 4 destroyers, while sinking 2 Japanese destroyers and crippling the battleship Hiei. But in the morning, the U.S. planes could still use their cratered airstrip. And the carrier Enterprise lurked 300 miles to the south.

At 6AM, dive bombers from Henderson hit Hiei. An hour later, Moret's Marine Corps TBF's put a torpedo in the drifting battleship. Around 10AM, they came at her again, and scored with another "fish."

Shortly, the Enterprise Avengers struck. Its Commander Air Department, John Crommelin, had sent in 15 Grumman TBF's under Lieutenant Al "Scoofer" Coffin. They were to attack Hiei, then land at Henderson Field. When they had launched in the early morning, a worried Crommelin had no idea if Henderson Field was American-held after the vicious battle, and his planes would not be able to abort back to Enterprise. Tearfully, he sent his boys in their Grummans on a possible one-way mission. They reached Hiei at 11:20 AM. The sky was full of black smoke, tracer fire and buzzing planes. Hiei fired back with everything she had, even incendiary 14-inch shells, unfired in the previous night's surface battle. The Avenger pilots saw the big shells fountain in the sea in an even row several miles astern. They flew at full throttle just over Hiei's burned and scorched decks. Seconds later, three torpedoes hit and exploded. But Hiei remained afloat. The Enterprise Avengers flew on to Henderson Field and found a friendly reception from American soldiers.

Six more of Col. Moret's Avengers hit Hiei with two more torpedos. Throughout the day, dive bombers and F4F's harassed the battleship. By sundown, the battered hulk was doomed, and Admiral Abe gave the order to scuttle her. The TBF's had scored their first major victory of the war.

Typical Monthly

Production Grumman

TBF-1 GM

TBM Total

Feb. 1942 5 - 5

June, 1942 60 - 60

Nov. 1942 100 1 101

July, 1943 150 100 250

June, 1944 - 300 300

March, 1945 - 400 400

TOTAL 2,291 7,546 9,837

Buy 'Rosie the Riveter' from Amazon.com

GM Enters the Production Battle - 1943

Grumman's plants were fully committed to the F6F Hellcat. As part of the national wartime production effort, General Motors (GM) made available to the war effort five of its factories - Tarrytown, Trenton, Linden, Bloomfield, and Baltimore, together organized into the "Eastern Aircraft Division" of the big auto maker. Grumman delivered two completed TBF's, with special removable "PK" screws instead of ordinary rivets. These planes helped the GM workers see how the Avengers were put together. Under the Navy's aircraft designation scheme the GM Avengers were identified as TBM. While GM's production started slowly in 1943, by the end of the year, it was out-producing Grumman, which phased out Avenger production completely by the end of 1943.

Rosie the Riveter

The Avenger is connected with the famous "Rosie the Riveter" character, symbol of American women who worked in wartime factories. Various accounts of the genesis of the "Rosie" figure have appeared. Norman Rockwell created the most familiar "Rosie" image for the cover of the Saturday Evening Post. Rockwell's image shows a muscular woman dressed in overalls, face mask and goggles on her head, eating a sandwich, her riveting tool in her lap, her feet resting on a copy of Mein Kampf. Two weeks after the cover illustration was published, stories appeared in the press extolling the achievement of Rose Hicker, a worker at GM's Eastern Aircraft Division in Tarrytown, who drove a record number of rivets into the wing of a TBM Avenger.

Check out Rosie the Riveter: Women Working on the Home Front in World War II by Penny Colman, at Amazon.com.

Modifications

After several hundred of the original TBF-1 were built, a few critical changes were made in the next variant, the TBF-1C. The pilot's single fuselage-mounted .30 caliber machine gun was replaced by two wing-mounted .50 caliber guns. The turret was also equipped with a .50 caliber weapon. And provisions for an internal fuel tank in the bomb bay plus two wing tanks more than doubled the Avenger's fuel capacity, from 335 to 726 gallons. The TBM-3 had these same features.

Starting in mid-1944, GM began building the TBM-3, with the more powerful (1900 hp) R-2600-20 engine and wing hard points for drop tanks or rockets. With over 4,600 TBM-3s built, they were the most numerous of the variants. However, even in February, 1945, most of the Avengers on the carriers in the Pacific were the Dash-1 versions. Only by V-J Day had the carrier TorpRons transitioned to the Dash-3.

Production of the Avenger stopped immediately after the end of hostilities.

O'Hare - Nov '43

In late 1943, the US Navy began its first systematic night fighting teams. The great fighter pilot Ed O'Hare, then the CAG Enterprise, was deeply involved in developing night fighter tactics. As the primitive radars were very bulky, they were carried on the Enterprise, on the roomy TBF Avengers, but not on the smaller and faster Hellcats. The plan required the ship's Fighter Director Officer (FDO) to spot the incoming Bettys at a distance and send the Avengers and Hellcats toward them. The radar-equipped Avengers would then lead the Hellcats into position behind the incoming bombers, close enough for the Hellcat pilots to spot visually the Betty's blue exhaust flames. Finally, the Hellcats would close in and shoot down the bombers. All the planes on both sides would be flying at low level. The plan was experimental, complicated, and risky.

The night of November 26-27, 1943 was the first combat test of the plan, following an earlier mission that hadn't contacted the Japs. The 'Black Panthers', as the night fighters were dubbed, included two sections of three planes. Both included two Hellcats and one Avenger. Butch led his section from his F6F, Warren Skon flew on his wing; Lt. Cdr. Phillips piloted the TBF with radarman Hazen Rand and gunner Alvin Kernan crewing the plane. In the confusing night action, O'Hare went down, most likely the victim of a lucky shot from the Betty, but possibly due to friendly fire. Read more in my article about Ed O'Hare.

Alvin Kernan wrote one of the best WW2 memoirs I have read, Crossing the Line: A Bluejacket's World War II Odyssey. It's out-of print, but I intentionally left the link to Amazon. (Another coincidental personal note - I studied Shakespeare under Professor Alvin Kernan in the early 1970's, when I had never even heard of Butch O'Hare, and didn't know an Avenger from a Spitfire. - SS)

In late 1943 and early 1944, more of the new Essex-class carriers deployed to the Pacific, with Avengers in their VT squadrons. Avengers participated in the historic raid Feb. 16 raid on Truk.

The U-Boat War

In the struggle for the North Atlantic, Avengers were credited with destroying 30 submarines, including the unique sinking of the Japanese cargo sub I-52. Flying from escort carriers (CVEs), TBFs were well-suited to the sub-killer role: long endurance, stable, large weapons capacity. They became the key strike aircraft in the hunter-killer groups that ranged the Atlantic: CVE's flying Avengers and Wildcats with destroyers in support.

Sinking of I-52

In an extraordinary engagement, Avengers from USS Bogue CVE-9, the top sub-killing CVE of the Atlantic, sank the Japanese transport submarine, I-52. In 1943 the Japanese and Germans worked out a plan to exchange critical materials via specialized cargo submarines: opium, rubber, quinine, tungsten, and molybdenum from the Japanese for German radar, bombsights, vacuum tubes, optical glass, ball bearings, etc.. In March, 1944, I-52 departed Kure, picked up cargo in Singapore and headed through the Indian Ocean, all monitored by U.S. intelligence. It rendezvoused with a German sub U-530 on June 23, in the mid-Atlantic, and picked up a German pilot who would guide I-52 into port at Lorient. There the exchange was planned to take place.

But Allied "Ultra" intercepts had pinpointed I-52's movements and even its cargo. Within hours of I-52's meeting with U-530, this information had been relayed to Bogue. The commander of its Composite Squadron 69 (VC-69), Lt. Cdr. Jesse Taylor, immediately took off in his TBF in pursuit of the Jap sub. As Taylor patrolled in the darkness, his radarman, Chief Ed Whitlock, picked up a blip. They went after it and dropped flares, lighting up the 350-foot long cargo sub. Taylor closed in, dropping two depth bombs. I-52 dived and the TBF dropped a sonobuoy into the water. The newly-developed sonobuoys picked up long-carrying underwater noises and transmitted these back to the carrier. Following the sonobuoy's signal, Taylor dropped a Mark 24 "Fido" acoustic torpedo. The sonobuoy transmitted the crunching sound of explosions back to Bogue. While Taylor thought he had sunk the sub, other Avengers soon picked up propeller beats. Bogue's CO, Captain A. B. Vosseller, ordered a second attack; William "Flash" Gordon flew his TBF to the site and dropped another torpedo. The I-52 swiftly went to the bottom, with a huge hole in her hull. Next morning, U.S. destroyers found I-52's flotsam: a ton of raw rubber, bit of silk, and even human flesh.

For over 50 years, I-52 lay at the bottom of the Atlantic. In 1998, the National Geographic Society sponsored a deep-sea submersible mission which found the I-52's remains. The October, 1999 issue featured this dramatic story, but I could not find any web links to it.

For more info on the submarine war in the Atlantic, check out the superlative article on the Avenger's role in the fight against the U-boats at uboat.net, a site which at this writing, boasts of over 12,700(!) pages.

But the TBFs' influence far exceeded the destruction of 30 subs. By their presence and activity, many more convoys arrived safely, an undramatic, but vital, result.

Into the Night - June 20, 1944

After the U.S. Navy's Hellcats destroyed over 350 Japanese planes in the "Marianas Turkey Shoot," Admiral Marc Mitscher wanted to follow up the aerial victory and sink the Japanese carriers as well. All day, and into the afternoon, Task Force 58's search planes, probed westward for the fleeing, defenseless enemy ships. Eventually, at 3:40 PM, Avenger pilot Lt. R.S. Nelson, from Enterprise, found Ozawa's force 275 miles to the west. Mitscher ordered an immediate strike; by 4:10 the planes were launched. Nonetheless, the risk to pilots was grave; there just wasn't enough daylight left for them to reach their quarry, hit them, and return. Mitscher's gamble reflected the cold and brutal calculus of war - he hoped his air crew losses would cost his side less than the damage they could do to the other side's ships. A couple hours later, at the extreme end of their range, the TBFs, Hellcats, and dive bombers caught the Japanese fleet.

Avengers from CVL-24 Belleau Wood sank the light carrier Hiyo. Belleau Wood's Air Group 24 launched 12 planes, including a division of four Avengers piloted by Lt.(jg) George P. Brown in the lead, Lt. Warren Omark, Benjamin C. Tate, and W.D. Luton. All four Avengers were armed with torpedoes. When they spotted the Jap carrier, Brown ordered the planes to fan out and approach from different angles. They dove through intense anti-aircraft fire, which struck Brown's TBF. George Platz and Ellis Babcock, the two crewmen in Brown's plane, realized their plane was afire and unable to reach Brown on the intercom, they parachuted and witnessed the attack from the water.

The wounded Brown grimly held his Avenger on track. He, Omark, and Tate launched their improved torpedos at the carrier. They struck home and the two aircrewmen in the water saw Hiyo sink 30 minutes later.

Brown and his plane disappeared. Omark flew back and made a nighttime landing on Lexington. Tate and Luton also flew back, had to ditch, and were recovered safely. American search planes rescued Platz and Babcock the next day.

The TBF's sinking of Hiyo was the only serious damage done to Japanese fighting ships by the 227 planes of the "mission beyond darkness." The Avengers' experience was typical of the day: 54 planes successfully launched, 29 of these were lost, plus 8 more operational losses. From these 37 planes, about 111 men went into the water - 67 were rescued. But a lot of brave young aviators died that day. Mitscher's gamble was probably correct, it just didn't pay off as well as all had hoped.

George Bush

Undoubtedly, the most famous man to fly an Avenger was George H.W. Bush, later the 41st President of the United States. He joined the Navy in 1942, and became the youngest naval aviator ever in June, 1943. He flew Avengers with VT-51, from USS San Jacinto. On September 2, 1944 he was shot down over Chichi Jima. While Bush parachuted safely and was rescued, neither of his crewmen survived. Bush earned a DFC for delivering his bombload after his TBF had been hit.

Read more about George Bush in WWII at the Naval Historical Center web site.

October, 1944

Avengers played a key role in sinking the Japanese super-battleship Musashi in the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea and in the next day's related action, the Battle of Leyte Gulf, CVE-based Avengers helped stave off the Japanese surface ships. TBF's also helped to sink Zuikaku and three light carriers on the 26th.

Lt. Cdr. Edward Huxtable, CO of Gambier Bay's VC-10, directed the Avengers and Wildcats in their attacks on the heavy Japanese ships. When Admiral Kurita's 4 battleships and 8 cruisers appeared off Samar on the morning of Oct.25, Gambier Bay and the other CVE's of Task Force 3 were cruelly exposed. Huxtable's TBM only had 100 rounds of .50 caliber ammunition, but he and other pilots made dummy runs on the Japanese fleet. After sinking Gambier Bay and three destroyers, the Japanese concluded that they were facing Essex-class carriers and they steamed back through San Bernardino Strait.

The End - 1945

Grumman's torpedo bombers sank the Yamato, in its last desperate run for Okinawa on April 7, 1945.

At the 1997 ceremonies for the Enlisted Combat Aircrew Roll of Honor, Yorktown veteran, Charles G. Fries, Jr. ARM2/C, a TBM tail gunner, described the attack.

In April 1945, we went after the last remnants of the Japanese Fleet, which comprised the battleship Yamato, the cruiser Yahagi, and two screen destroyers. When we went to look for them it was overcast, and the TBF crews had to find them, which we did. When we came into range, the squadrons split into two sections. The admirals wanted very badly to bring down the battleship, and if necessary every airplane would hit it. It turned out, that was not necessary. The first TBM's got the wagon, and she was severely damaged, ready to sink.

So we went after the cruiser, whose armor plating was at a different depth. In consequence we had to change the depth setting on the torpedo so it wouldn't go under the cruiser, so it would hit Yahagi at the appropriate point and put a hole in her.

It was a little hairy because you couldn't see what you were doing. You could only get in there up to your armpit, so you were feeling your way. The wrench that turned the indicator changed the depth setting. This was right next to the arming wires that ran from the bulkhead to the torpedo's fuse. If you pulled the wrong wire, we were told the air stream coming through could actually arm the torpedo. If it were hit in any way it could have been a problem to us.

We changed the depth setting and went after the cruiser. Both big ships and the destroyers put up a lot of flak. After firing our torpedo, we were pleased to see the cruiser go down. Later another destroyer went down too. One pilot's torpedo hung up and he had to make two more runs. He got the torpedo off, so we sank three of the four Japanese ships. As far as we were concerned, the Japanese fleet was no more.

As young kids, we were so elated to see those ships go down. The wagon rolled over on her side and eventually went under. The cruiser slipped up into the air, bow first and then slid back down into the water like a toy. My first feeling of elation recalled the Pearl Harbor attack. We felt like we were getting even. However that was soon followed by a great feeling of sadness.

It was strange to see all the Japanese sailors in the water, and wondering to this day if there was any survivors. If there were I would truly like to talk to them and get their side of the story. At this point in our lives, in our middle seventies, we are more reflective. We realize that it's young kids who go to war. I don't know who starts them, but it is not a pleasant to consider all those fellows that didn't make it were somebody's son. They were only kids doing what they were told, the same as we were.

So in this point of one's life, there isn't any malice left.

Read more Aircrews' War Stories at this website.

Post War

After the war, Avengers continued flying in the U.S. Navy, primarily in anti-submarine, Electronic Counter-Measures (ECM), as missile platforms, and for training. Large numbers of Avengers found postwar roles with Canada, France, Japan and the Netherlands, some still serving in 1960. Some were converted to civilian use as fire-fighters.

Survivors/Museums

42 still airworthy, according to Warbird Alley. A TBM Avenger is on display at New York City's USS Intrepid Sea-Air-Space Museum.

Avenger variants

Grumman TBF's

XTBF-1: two prototypes, R-2600-8 engine

TBF-1: initial production version similar to second prototype; total 2,291 excluding prototypes but including -1Bs and -1Cs

TBF-1B: variant for British with minor differences: initially designated Tarpon TR.Mk 1; 395 conversions

TBF-1C: as TBF-1 but maximum fuel capacity increased from 335 to 726 gallons with two wing drop tanks and bomb bay ferry tank, two 0.5-inch wing guns

TBF-1CP: conversions of TBF-1C with trimetrogen reconnaissance cameras in fan to give wide coverage

TBF-1D: conversion with RT-5/APS-4 radar in wing pod: TBF-1CD similar conversion of TBF-1C

TBF-IE conversion with special radar and additional avionics

TBF-1J: conversion for Arctic operations, including a high-capacity cockpit heater, bad weather avionics and lighting, and special ice protection

TBF-1L: searchlight on retractable mount extending from bomb bay. Quickly dropped as the searchlight made the plane a fine target for submarine anti-aircraft fire.

TBF-1P: TBF-1 conversion, as TBF-1CP

XTBF-2: conversion of TBF-1 No. 00393 with 1,900 hp XR-2600-10 engine

XTBF-3: two TBF-1s completed with engine installation of TBF-3

General Motors TBM's

TBM-1: similar to TBF-1: total 550

TBM-IC: similar to TBF-1C: total 2,336

TBM-1D/E/J/L/P: similar to corresponding TBFs

TBM-2: conversion of TBM-1 No, 24580 with XR-2600-10 engine

XTBM-3: conversions of four TBM-1Cs with R-2600-20

TBM-3: major production model with R-2600-20 engine and outer wing drop tanks or rockets: total 4,657

TBM-3D: conversion with APS-4 radar on right

TBM-3E: conversions with strengthened structure and RT-5/APS-4 radar in pod under right wing

TBM-3E2: updated TBM-3E with extra avionics

TBM-3H: conversions with surface-search radar

TBM-3J: conversions as TBF-1J

TBM-3L: conversions as TBF-1L

TBM-3P: photo-reconnaissance conversions, differing from TBF-1P

TBM-3U: conversions for utility and target towing

XTBM-4: three new-build aircraft with redesigned wing with different fold system and re-stressed to 5g maneuvers, production of 2,141 TBM-4 cancelled at VJ-Day

General characteristics

Crew: 3

Length: 40 ft 11.5 in (12.48 m)

Wingspan: 54 ft 2 in [94] (16.51 m)

Height: 15 ft 5 in (4.70 m)

Wing area: 490.02 ft² (45.52 m²)

Empty weight: 10,545 lb (4,783 kg)

Loaded weight: 17,893 lb (8,115 kg)

Powerplant: 1× Wright R-2600-20 radial engine, 1,900 hp (1,420 kW)

Performance

Maximum speed: 275 mph [95] (442 km/h)

Range: 1,000 mi (1,610 km)

Service ceiling: 30,100 ft (9,170 m)

Rate of climb: 2,060 ft/min (10.5 m/s)

Wing loading: 36.5 ft·lbf² (178 kg/m²)

Power/mass: 0.11 hp/lb (0.17 kW/kg)

Armament

Guns:

1 × 0.30 in (7.62 mm) nose-mounted M1919 Browning machine gun(on early models)

2 × 0.50 in (12.7 mm) wing-mounted M2 Browning machine guns

1 × 0.50 in (12.7 mm) dorsal-mounted M2 Browning machine gun

1 × 0.30 in (7.62 mm) ventral-mounted M1919 Browning machine gun

Rockets:

up to eight 3.5-Inch Forward Firing Aircraft Rockets, 5-Inch Forward Firing Aircraft Rockets or High Velocity Aerial Rockets

Bombs:

Up to 2,000 lb (907 kg) of bombs or

1 × 2,000 lb (907 kg) Mark 13 torpedo

Flight 19 was the designation of five TBM Avenger torpedo bombers that disappeared on 5 December 1945 during a United States Navy-authorized overwater navigation training flight from Naval Air Station Fort Lauderdale, Florida.[1] The assignment was called "Navigation problem No. 1", a combination of bombing and navigation, which other flights had completed or were scheduled to undertake that day.[2]

All 14 airmen on the flight were lost, as were all 13 crew members of a PBM Mariner flying boat assumed to have exploded in mid-air while searching for the flight.[citation needed] Navy investigators could not determine the cause for the loss of Flight 19 but said the aircraft may have become disoriented and ditched in rough seas after running out of fuel.[citation needed]

The pulp magazine Argosy published an account of the incident. Subsequently, writers on the paranormal such as Charles Berlitz and Richard Winer added their own research to associate the incident with the Bermuda Triangle. The flight also features in the 1977 science fiction film Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Navigation training flight

Flight 19 undertook a routine navigation and combat training exercise in VTB-type aircraft.[3] The flight leader was United States Navy Lieutenant Charles Carroll Taylor who had about 2,500 flying hours, mostly in aircraft of this type, while his trainee pilots had 300 total, and 60 flight hours in the Avenger.[2] Taylor had recently arrived from NAS Miami where he had also been a VTB instructor. The student pilots had recently completed other training missions in the area where the flight was to take place.[2] They were US Marine Captains Edward Joseph Powers and George William Stivers, US Marine Second Lieutenant Forrest James Gerber and USN Ensign Joseph Tipton Bossi.

The aircraft were four TBM-1Cs, BuNo 45714, 'FT3', BuNo 46094, 'FT36', BuNo 46325, 'FT81', BuNo 73209, 'FT117', and one TBM-3, BuNo 23307, 'FT28'.

Each aircraft was fully fueled, and during pre-flight checks it was discovered they were all missing clocks. Navigation of the route was intended to teach dead reckoning principles, which involved calculating among other things elapsed time. The apparent lack of timekeeping equipment was not a cause for concern as it was assumed each man had his own watch.[2] Takeoff was scheduled for 13:45 local time, but the late arrival of Taylor delayed departure until 14:10.[2] Weather at NAS Fort Lauderdale was described as "... favorable, sea state moderate to rough."[2] Taylor was supervising the mission, and a trainee pilot had the role of leader out front.

Called "Naval Air Station, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, navigation problem No. 1,"[1] the exercise involved three different legs, but the actual flight should have flown four. After take off, they flew on heading 091° (almost due east) for 56 nmi (64 mi; 104 km) until reaching Hen and Chickens Shoals where low level bombing practice was carried out. The flight was to continue on that heading for another 67 nmi (77 mi; 124 km) before turning onto a course of 346° for 73 nmi (84 mi; 135 km), in the process over-flying Grand Bahama island. The next scheduled turn was to a heading of 241° to fly 120 nmi (140 mi; 220 km) at the end of which the exercise was completed and the Avengers would turn left to then return to NAS Ft. Lauderdale.[2]

Map of Flight 19's navigation exercise and final position on December 5, 1945. D. 100 nautical miles (190 km) 0. The Bermuda Triangle 1. Start exercise at NAS Fort Lauderdale 14:10. 2. Drop bombs at Hen and Chickens shoals until around 15:00. 3. Proceed on new heading 346° for 73 nautical miles (140 km). 4. Fly on third heading 241° for 120 nautical miles (220 km) to point north of NAS Fort Lauderdale. 5. Return to NAS Fort Lauderdale 26°N 80°W 6. 15:00–17:50 exact position unknown. 7. 17:50 radio triangulation establishes flight's position to within 100 nautical miles (190 km) of 29°N 79°W and their last reported course, 270°. 8. PBM-5 (BuNo 59225) takes off from NAS Banana River 19:27. 9. 19:50 PBM-5 explodes near 28°N 80°W. 10. The Florida Keys, where Taylor thought he was.

Radio conversations between the pilots were overheard by base and other aircraft in the area. The practice bombing operation was carried out because at about 15:00 a pilot requested and was given permission to drop his last bomb.[2] Forty minutes later, another flight instructor, Lieutenant Robert F. Cox in FT-74, forming up with his group of students for the same mission, received an unidentified transmission.[1]

A male asked Powers, one of the students, for his compass reading. Powers replied: "I don't know where we are. We must have got lost after that last turn." Cox then transmitted; "This is FT-74, plane or boat calling 'Powers' please identify yourself so someone can help you." The response after a few moments was a request from the others in the flight for suggestions. FT-74 tried again and a man identified as FT-28 (Taylor) came on. "FT-28, this is FT-74, what is your trouble?" "Both of my compasses are out", Taylor replied, "and I am trying to find Fort Lauderdale, Florida. I am over land but it's broken. I am sure I'm in the Keys but I don't know how far down and I don't know how to get to Fort Lauderdale."[2]

FT-74 informed the NAS that aircraft were lost, then advised Taylor to put the sun on his port wing and fly north up the coast to Fort Lauderdale.[2] Base operations then asked if the flight leader's aircraft was equipped with a standard YG (IFF transmitter), which could be used to triangulate the flight's position, but the message was not acknowledged by FT-28. (Later he would indicate that his transmitter was activated.) Instead, at 16:45, FT-28 radioed: "We are heading 030 degrees for 45 minutes, then we will fly north to make sure we are not over the Gulf of Mexico." During this time no bearings could be made on the flight, and IFF could not be picked up. Taylor was told to broadcast on 4805 kilocycles. This order was not acknowledged so he was asked to switch to 3,000 kilocycles, the search and rescue frequency. Taylor replied – "I cannot switch frequencies. I must keep my planes intact."[2]

At 16:56 Taylor was again asked to turn on his transmitter for YG if he had one. He did not acknowledge but a few minutes later advised his flight "Change course to 090 degrees (due east) for 10 minutes."About the same time someone in the flight said "Dammit, if we could just fly west we would get home; head west, dammit."[2]This difference of opinion later lead to questions about why the students did not simply head west on their own.[4] It has been explained that this can be attributed to military discipline.[4]

As the weather deterioated, radio contact became intermittent, and it was believed that the five aircraft were actually by that time more than 200 nmi (230 mi; 370 km) out to sea east of the Florida peninsula. Taylor radioed "We'll fly 270 degrees west until landfall or running out of gas"[2] and requested a weather check at 17:24. By 17:50 several land based radio stations had triangulated Flight 19's position as being within a 100 nmi (120 mi; 190 km) radius of 29°N 79°W;[2] Flight 19 was north of the Bahamas and well off the coast of central Florida, but nobody transmitted this information on an open, repetitive basis.[2]

At 18:04 Taylor radioed to his flight "Holding 270, we didn't fly far enough east, we may as well just turn around and fly east again". By that time, the weather had deteriorated even more and the sun had since set. Around 18:20, Taylor's last message was received. He was heard saying "All planes close up tight ... we'll have to ditch unless landfall ... when the first plane drops below 10 gallons, we all go down together."[2][3] At the same time, in the same area, SS Empire Viscount, a British-flagged tanker, radioed that she was in heavy seas and high winds northeast of the Bahamas, where Flight 19 was about to ditch.[2]

[edit] PBM-5 (BuNo 59225)

PBM-5 (BuNo 59225)

PBM-5 Mariner VP-50 Blue Dragons (BuNo 59256) in April 1956-similar to BuNo 59225. (Note: "BuNo" stands for Bureau Number.[5])

Occurrence summary

Date December 5, 1945

Type Presumed mid-air explosion

Site 28.59°N 80.25°W

Crew 13

Fatalities 13

Survivors none

Aircraft type PBM-5 Mariner

Operator United States Navy

Flight origin NAS Banana River

Destination NAS Banana River

Earlier, as it became obvious the flight was indeed lost, several air bases, aircraft, and merchant ships were alerted. A PBY Catalina left after 18:00 to search for Flight 19 and guide them back if they could be located.[2] After dark, two PBM Mariner seaplanes originally scheduled for their own training flights were diverted to perform square pattern searches in the area west of 29°N 79°W. PBM-5 BuNo 59225 took off at 19:27 from Banana River Naval Air Station (now Patrick Air Force Base), called in a routine radio message at 19:30 and was never heard from again.[2]

At 19:50, the tanker SS Gaines Mills reported seeing a mid-air explosion, then flames leaping 100 ft (30 m) high and burning on the sea for 10 minutes. The position was 28.59°N 80.25°W. Captain Shonna Stanley, reported searching for survivors through a pool of oil, but found none. The escort carrier USS Solomons also reported losing radar contact with an aircraft in the same position and time.[2]

[edit] Investigation

A 500-page Navy board of investigation report published a few months later made several observations.

Taylor had mistakenly believed that the small islands he passed over were the Florida Keys, so his flight was over the Gulf of Mexico and heading northeast would take them to Florida. It was determined that Taylor had passed over the Bahamas as scheduled, and he did in fact lead his flight to the northeast over the Atlantic. The report noted that some subordinate officers did likely know their approximate position as indicated by radio transmissions stating that flying west would result in reaching the mainland.

Taylor, although an excellent combat pilot and officer with the Navy, had a tendency to "fly by the seat of his pants", getting lost several times in the process.[citation needed] It was twice during such times that he had to ditch his plane in the Pacific and be rescued.

It wasn't Taylor's fault because the compasses stopped working.

The loss of PBM-5 BuNo 59225 was attributed to a mid-air explosion.[1]

This report was subsequently amended "cause unknown" by the Navy after Taylor's mother contended that the Navy was unfairly blaming her son for the loss of five aircraft and 14 men, when the Navy had neither the bodies nor the airplanes as evidence.[citation needed]

Had Flight 19 actually been where Taylor believed it to be, landfall with the Florida coastline would have been reached in a matter of 10 to 20 minutes or less, depending on how far down they were. However, a later reconstruction of the incident showed that the islands visible to Taylor were probably the Bahamas, well northeast of the Keys, and that Flight 19 was exactly where it should have been. The board of investigation found that because of his belief that he was on a base course toward Florida, Taylor actually guided the flight further northeast and out to sea. Further, it was general knowledge at NAS Fort Lauderdale that if a pilot ever became lost in the area to fly a heading of 270° west (or in evening hours toward the sunset if the compass had failed). By the time the flight actually turned west, they were likely so far out to sea they had already passed their aircraft's fuel endurance. This factor combined with bad weather, and the ditching characteristics of the Avenger,[3] meant that there was little hope of rescue, even if they had managed to stay afloat.

It is possible that Taylor overshot Castaway Cay and instead reached another land mass in southern Abaco Island. He then proceeded northwest as planned. He fully expected to find the Grand Bahama Island laying in front of him as planned. Instead, he eventually saw a land mass to his right side, the northern part of Abaco Island. Believing that this landmass to his right was the Grand Bahama Island and his compass was malfunctioning, he set a course to what he thought was southwest to head straight back to Fort Lauderdale. However, in reality this changed his course further northwest, toward open ocean.

To further add to his confusion, he encountered a series of islands north of Abaco Island, which looks very similar to the Key West Islands. Eventually, to Taylor's horror, he was still in the middle of the ocean instead of over Fort Lauderdale. The control tower then suggested that Taylor's team should fly west, which would have taken them to the landmass of Florida eventually. Instead of following his compass, Taylor headed for what he thought was west, but in reality was northwest, almost parallel to Florida.

After trying that for a while and no land in sight, Taylor decided that it was impossible for them to fly so far west and not reach Florida. He believed that he might have been near the Key West Islands. What followed was a series of serious confusions between Taylor, his team and the control tower. Taylor was not sure whether he was near Bahama or Key West, and he was not sure which direction was which due to compass malfunction. The control tower informed Taylor that he could not be in Key West since the wind that day did not blow that way. Some of his teammates believed that their compass was working. Taylor then set a course northeast according to their compass, which should take them to Florida if they were in Key West. When that failed, Taylor set a course west according to their compass, which should take them to Florida if they were in Bahama. If Taylor stayed this course he would have reached land before running out of fuel. However, at some point Taylor decided that he had tried going west enough. He then once again set a course northeast, thinking they were near Key West after all. Finally, his flight ran out of fuel and may have crashed into the ocean somewhere north of Abaco Island and east of Florida.[6]

[edit] Unrelated Avenger wreckage

In 1986, the wreckage of an Avenger was found off the Florida coast during the search for the wreckage of the Space Shuttle Challenger.[citation needed] Aviation archaeologist Jon Myhre raised this wreck from the ocean floor in 1990. He was convinced it was one of the missing planes, but positive identification could not be made. In 1991, the wreckage of five Avengers was discovered off the coast of Florida, but engine serial numbers revealed they were not Flight 19. They had crashed on five different days all within 1.5 mi (2.4 km) of each other.[7] Records revealed that the various discovered aircraft, including the group of five, were declared either unfit for maintenance/repair or obsolete, and were simply disposed of at sea.[7]

Records also showed training accidents between 1942 and 1945 accounted for the loss of 95 aviation personnel from NAS Fort Lauderdale[8] In 1992, another expedition located scattered debris on the ocean floor, but nothing could be identified. In the last decade[when?], searchers have been expanding their area to include farther east, into the Atlantic Ocean.

[edit] Men of Flight 19 and PBM-5 BuNo 59225

[edit] Charles Carroll Taylor

The flight leader, Lieutenant Charles Carroll Taylor (born October 25, 1917), graduated from Naval Air Station Corpus Christi in February 1942 and became a flight instructor in October of that year.

The men of Flight 19 and PBM-5 BuNo 59225[1]

Aircraft

number Pilot Crew Series Nr.

FT-28 Charles C. Taylor, Lieutenant, USNR George Devlin, AOM3c, USNR

Walter R. Parpart, ARM3c, USNR 23307

FT-36 E. J. Powers, Captain, USMC Howell O. Thompson, SSgt., USMCR

George R. Paonessa, Sgt., USMC 46094

FT-3 Joseph T. Bossi, Ensign, USNR Herman A. Thelander, S1c, USNR

Burt E. Baluk, JR., S1c, USNR 45714

FT-117 George W. Stivers, Captain, USMC Robert P. Gruebel, Pvt., USMCR

Robert F. Gallivan, Sgt., USMC 73209

FT-81 Robert J. Gerber, 2nd LT, USMCR William E. Lightfoot, Pfc., USMCR* 46325

BuNo 59225 Walter G. Jeffery, Ltjg, USN Harrie G. Cone, Ltjg, USN

Roger M. Allen, Ensign, USN

Lloyd A. Eliason, Ensign, USN

Charles D. Arceneaux, Ensign, USN

Robert C. Cameron, RM3, USN

Wiley D. Cargill, Sr., Seaman 1st, USN

James F. Jordan, ARM3, USN

John T. Menendez, AOM3, USN

Philip B. Neeman, Seaman 1st, USN

James F. Osterheld, AOM3, USN

Donald E. Peterson, AMM1, USN

Alfred J. Zywicki, Seaman 1st, USN

Related content

Comments: 8

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

I remember making a model of this particular plane, FT-28 flown by taylor and discovering a photof that exact plane online. I notice the number 28 painted on the underside of the left wing.

great work by the way. Hopefully someday Flight 19 is found.

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

Been watching Battlefront 360. a mini series about the Enterprise in WWII. You don't realize jsut how hard they had it back then..

Now great looking plane, Bagera.. Maybe do one in the colors and markings of George W Bush?

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

oh, and you clever bastard....... (I'll let everyone else take a guess as to what I'm getting at, hint: look at the tail)

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

is it just me, or does this sucker look a little... bland... (I know the real ones were) maybe some weathering would help it along. (some oil on the coaling, faded paint on the leading edges, etc.)

👍: 0 ⏩: 0