HOME | DD

DavisPK — Call It Courage - Homeward

DavisPK — Call It Courage - Homeward

#awesome #bravery #classic #inspiring #sperry #superior #superlative

Published: 2023-08-12 01:31:18 +0000 UTC; Views: 3142; Favourites: 33; Downloads: 0

Redirect to original

Description

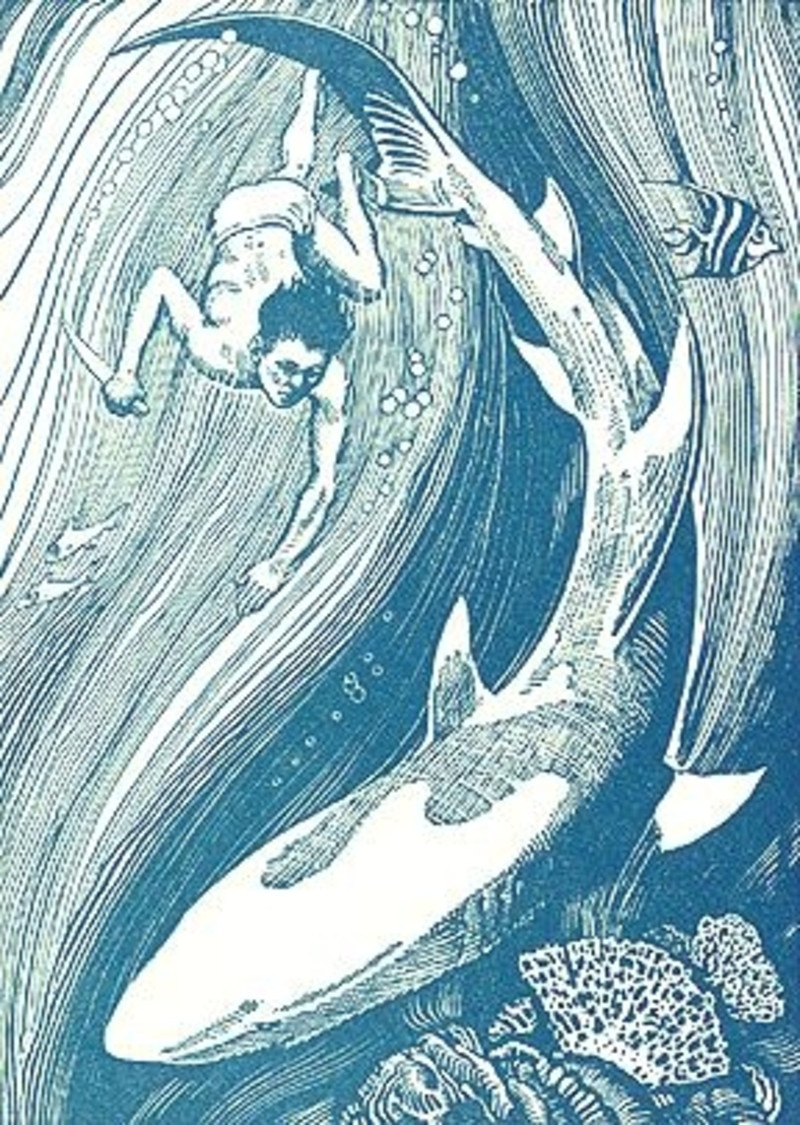

A CHILL sweat broke out over Mafatu' s body. He crouched there listening, unable for the moment to make a single movement. The rhythmic message that boomed across the mountain brought him a message of doom. Thump-thump THUMP! Thump-thump THUMP! It shivered along his nerves, setting his hair on edge. Warily, moving with utmost caution, Mafatu crept out of the house. The beach was softly brilliant in the light of the waning moon. Any figure moving along the sand he could have seen instantly. He stopped, every nerve strung like a wire: the beach was deserted, the jungle silent and black with mystery. The boy rose to his feet. Swift as a shadow he turned into the undergrowth where the trail led to the high plateau. The jungle had never seemed so dark, so ominous with peril. The tormented roots of the mo trees clutched at him. Lianas tripped him. Tree-ferns, ghostly in the half-light, rustled about him as he passed, their muted hush seeming to say: "Not yet, Mafatu, not yet." ... By the time he reached the plateau he was breathless and panting. He dropped to his knees and crawled forward, an inch or two at a time. One false move might spell destruction. But he had to know, he had to know. ... Thump-thump THUMP! The measured booming grew louder with every inch that he advanced, Now it pounded in his ears, reverberated through his body, thrummed his nerves. Somewhere below in darkness, black hands drew forth from hollowed logs a rhythm that was a summation of life, a testament of death. Uri crept close to his master's aide, the hair ridging on his neck, his growl drowned in the thunder. Now the boy could see into the cleared circle of the Sacred Place. Leaping fires lighted a scene that burned itself forever into his memory. Fires blazed against the basalt cliffs, spurts of flame that leaped and danced showers of sparks borne off on the back of the night wind. Now a deep wild chanting rose above the booming of the drums. From his vantage point Mafatu saw six war canoes drawn up on the beach. Mighty canoes they were, with high- curving stems and decorations of white shell that caught the firelight in savage patterns. But what held the boy's eyes in awful trance were the figures, springing and leaping about the flames: figures as black as night's own face, darting, shifting, bounding toward the sky. The eaters-of- men.... Firelight glistened on their oiled bodies, on flashing spears and bristling decorations. High above the drums' tattoo rose the mournful note of the conch shells, an eerie wailing, like the voices of souls last in interstellar space. Mafatu saw that the savages were armed with ironwood war clubs— clubs studded with sharks' teeth or barbed with the sting-ray's spike. Zigzags of paint streaked their bodies. And towering above all, the great stone idol looked down with sightless eyes, just as it had looked for untold centuries. Mafatu, lying there on the ledge of basalt, watched the strange scene, powerless to move, and he felt Doom itself breathing chill upon his neck. He drew back from the edge of the cliff. He must flee! In that very instant he heard a crashing in the undergrowth, not twenty yards away. A guttural shout ripped the darkness. The boy flung a desperate glance over his shoulder. Four black figures were tearing toward him through the jungle; he could see them now. He turned and ran blindly down the trail whence he had come. Slipping, sliding, stumbling, his breath all but choking in his throat. He felt like a man drowning in ice-cold water. He felt as he had sometimes felt in dreams, fleeing on legs that were weighted. Only one thought gave him courage as he ran: his canoe, ready and waiting. His canoe. If only he could reach it, shove it into the water before the savages overtook him. Then he would be safe.... He knew this trail as he knew the back of his hand. That knowledge gave him an advantage. He could hear his pursuers, slipping, stumbling through the brush, shouting threats in a language strange to his ears. But there was no mistaking the meaning of their words. On the boy dashed, fleet as an animal. Thoms and vines clutched at him. Once he tripped and sprawled headlong. But he was up and away in an instant. Through the trees he caught a glimpse of white beach and his heart surged. Then he was speeding across the sand, Uri at his heels. The canoe was at the lagoon's edge. The boy fell upon the thwart, shoved the craft into the water. The logs under the stem robed easily. In that second, the black men, yelling wildly, broke from the jungle and dashed across the beach. Mafatu was not a minute too soon. He leaped aboard and ran up the sail. The savages rushed after him into the shallows. A gust of wind filled the sail. It drew smartly. How the men were swimming. One of them, in the lead, reached to lay hold of the outrigger. His black hand clutched the purau pole. The canoe slacked. Mafatu could see the gleam of bared teeth. The boy lifted the paddle and cracked it down.... With a groan the man dropped back into the water. The canoe, freed, skimmed out toward the barrier-reef. The savages stopped, turned back toward shore. Then they were running back to the trail that led across the island, shouting to their fellows as they ran. Mafatu knew that it was only a question of minutes until the whole pack would be aroused and in pursuit. But he had the advantage of a head start and a light craft, while their canoes would have to beat around the southern point of the island before they could catch up with him. If only the breeze held.... Mafatu remembered then that the canoes he had seen drawn up on the beach had not been sailing canoes. There were strong arms to propel those black canoes, to overtake him if they could. Mafatu's canoe, so slim and light, sped like a zephyr across the lagoon. The tide was on the ebb, churning in its race through the passage into the outer ocean. The boy gripped the steering paddle and offered up a prayer. Then he was caught in the riptide. The outrigger dashed through the passage, a chip on a torrent. The wind of the open sea rushed to greet it. The sail filled; the outrigger heeled over. Mafatu scrambled to windward to lend his weight for ballast. He was off! Homeward, homeward. ... Soon, rising above the reef thunder, the boy could hear a measured sound of savage chanting. They were after him! Looking back over his shoulder, he could see the dark shapes of the canoes rounding the southern headland. Moonlight shone on half a hundred wet paddles as they dipped and rose to the rhythm of the chant. It was too dark to see the eaters-of-men themselves, but their wild song grew ever more savage as they advanced. The breeze was almost dead aft. The crab-claw sail swelled smooth and taut, rigid as a block of silver against the sky. The little canoe, so artfully built, ran with swell and favoring wind, laying knots behind her. She was as fleet and gracile as the following gulls. But the eaters-of- men were strong paddlers with death in their hearts. Their motu tabu had been profaned by a stranger. Vengeance powered their muscles. They were tireless. On they came. The wind dropped. Imperceptibly at first. Sensing it, Mafatu whistled desperately for Maui. "Maui e! Do not desert me," he prayed. "This last time— lend me your help." Soon the black canoes were so close that the boy could see the shine of dark bodies, the glint of teeth, and flash of ornament. If the wind died, he was lost. ... Closer, closer the canoes advanced. There were six of them, filled each with ten warriors. Some of them leaped to their feet brandished their clubs, shouted at the boy across the water. They were a sight to quake the stoutest heart. With every second they were cutting down the distance which separated their canoes from Mafatu's. Then the wind freshened. Just a puff, but enough. Under its impetus the little canoe skimmed ahead while the boy's heart gave an upward surge of thanks. Maui had heard his prayer and answered. Day broke over the wide Pacific. There were the six black canoes, paddles dashing, now gaining, now losing. The boy was employing every art and wile of sailing that he knew. As long as the wind held he was safe. He managed his little craft to perfection, drawing from it every grace of speed in flight. He knew that with coming night the wind might drop, and then— He forced the thought from his mind. If the wind deserted him it would mean that Maui had deserted him, too. But the savages would never get him! It would be Moana, the Sea God's turn. The boy looked down into the blue depths over side and his smile was grim: "Not yet, Moana," he muttered fiercely. "You haven't won. Not yet."... "Te mori" he whispered at last, his voice a thread of awe. 'The lagoon-fire" There came a whir and fury in the sky above, a beat of mighty wings: an albatross, edged with light, circled above the canoe. It swooped low, its gentle, questing eyes turned upon the boy and his dog. Then the bird lifted in its efforts less flight, flew straight ahead and vanished into the lagoon-fire. And then Mafatu knew. Hikueru, his home-land, lay ahead. Kivi.... A strangled cry broke from the boy. He shut his eyes tight and there was a taste of salt, wet upon his lips. The crowd assembled upon the beach watched the small canoe slip through the reef-passage. It was a fine canoe, an artfully built. The people thought at first that it was empty. Silence gripped them, and a chill of awe touched them like a cold hand. Then they saw a head lift above the gunwale, a thin body struggle to sit upright, clinging to the mid-thwart. " Aue te ciue!” The cry went up from the people in a vast sigh. So they might speak if the sea should give up its dead. But the boy who dropped over side into the shallows and staggered up the beach was flesh and blood, albeit wasted and thin. They saw that a necklace of boar's teeth shone upon his chest; a splendid spear flashed in his hand. Tavana Nui, the Great Chief of Hikueru, went forward to greet the stranger. The brave young figure halted, drew itself upright. "My father," Mafatu cried thickly, "I have come home." The Great Chief’s face was transformed with joy. This brave figure, so thin and straight, with the fine necklace and the flashing spear and courage blazing from his eyes— his son? The man could only stand and stare and stare, as if he could not believe his senses. And then a small yellow dog pulled himself over the gunwale of the canoe, fell at his master's feet, Uri.... Far overhead an albatross caught a light of gold on its wings. Then Tavana Nui turned to his people and cried: "Here is my son come home from the sea. Mafatu, Stout Heart. A brave name for a brave boy!" Mafatu swayed where he stood. "My father, I ..." Tavana Nui caught his son as he fell. It happened many years ago, before the traders and missionaries first came into the South Seas, while the Polynesians were still great in numbers and fierce of heart. But even today the people of Hikueru sing this story in their chants and tell it over the evening fires. From Call It Courage, text and illustrations by Armstrong Perry. 1940. 1941 Newbery Medal winner. misterscribbles.blogspot.com/2…

Related content

Comments: 7

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 1 ⏩: 1

👍: 1 ⏩: 1

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 1 ⏩: 1

👍: 1 ⏩: 0