HOME | DD

Eldr-Fire — The Heretic of Plovdiv

Eldr-Fire — The Heretic of Plovdiv

#autumn #bible #bulgaria #bulgarian #christian #christianity #gospel #heresy #heretic #heretical #historical #history #nun #orthodox #woman #women #historicalcostume #medieval #medievaldress #middleages #historicalfashion #medievallady #historicaldress #historicallyaccurate #historydrawing #historyfashion #historyart

Published: 2021-08-25 18:16:32 +0000 UTC; Views: 9151; Favourites: 30; Downloads: 2

Redirect to original

Description

They say that heresy is in the eye of the beholder. A visionary to some is a blasphemer to others. Medieval Europe was full of people who were enthusiastic about reforming the Church to be more in line with the vision Christ set out for his apostles. But when reforming the Church meant criticizing its current leaders, the line between reform and heresy could be a dangerous one to toe.

In 10th century Bulgaria, one group seeking radical reform of Christianity was the Bogomils. Named for their founding priest, whose name translates to "beloved by God", they formed in Bulgaria before spreading to other parts of the Byzantine Empire. Their exact origins are much debated. By the time we have records of Orthodox churchmen railing against them, they seem to have already achieved a significant foothold in Bulgaria. But who were the Bogomils, what did they believe, and why were they considered a big enough threat to be persecuted as heretics?

The Bogomils were dualists who lived a strict ascetic lifestyle. Like earlier heretics in Christianity's history, they believed that the material world was created by Satan, not by God the Father, and that Satan was the elder brother of Jesus. Because of this, everything physical in the world was evil. The soul, the only part of a human which came from God, was therefore considered to be trapped in the prison of the body. This core belief had huge ramifications for how the Bogomils interacted with the world. Their leaders were celibate and taught that people had to reject sex in order to be saved. They refused to eat meat or drink wine, and the leaders owned no property and completed no manual labour. Instead, they would wander to the houses of the lay believers and ask for food and shelter. They underwent rigorous fasting and refused the celebration all religious holidays and feast days.

But the beliefs of the Bogomils went beyond how to conduct their own lives. They rejected the entire Old Testament, much as the Marcionites had done in the second century. The Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles were of central importance to them, as were apocryphal texts like the Vision of Isaiah. Even the books of the Bible they did accept, though, were radically reinterpreted. Miracles, for example, were considered to be either the deceptions of demons or mere allegories. What really got them into trouble, however, was that their rejection of the physical world was also a rejection of the Incarnation of Christ, or the belief that God had taken physical flesh when he was born through Mary as Jesus. This, of course, is one of the fundamental beliefs of Christianity. Early Christians had argued vociferously about the divine to human ratio in Christ, but by the time of the Bogomils, the orthodox position that Jesus was both a divine and physical being had long been cemented. This position was considered essential to understanding that God had redeemed the physical world of humanity through Christ's Incarnation and death on the cross. By rejecting Christ's incarnation on Earth as a mere act of theatre, the Bogomils waded into deeply heretical territory.

Because the Bogomils had such a different interpretation of Christianity, they rejected the authority of the established Church. They taught that the Orthodox clergy were like the Pharisees, hypocrites who didn't live up to the moral standards expected of priests. They also argued that all religious icons and images were idols, echoing the early iconoclastic controversies of the Byzantine Church. This criticism extended even to the very church buildings themselves, leading the Bogomils to worship outside and in their own homes instead. They ridiculed the cults of saints and attributed miracles at saints' tombs to the trickery of demons. In particular, they dismissed the idea that Mary was an important figure, since they did not believe that she had really given birth to Jesus. A distinctly Bogomil belief was the hatred of the cross. While Orthodox Christians viewed the cross as a sign of Christ's triumph over death, the Bogomils considered it an insult to Christ to display the implement of his state execution. They wouldn't make the sign of the cross when they prayed, and their enemies alleged that they even chopped up wooden crosses and made tools out of them. They also refused to repeat any prayer except the "Our Father", which they repeated several times a day and several times a night. All other prayers and liturgy were unnecessary to them. Even Eucharist and baptism, the most important rituals of the Church, were dismissed by the Bogomils as mere bread and water.

Bulgaria had only been converted to Christianity in the 9th century, and it's thought that this may be part of why Bogomilism could flourish there. Competition from Catholic and Orthodox Christians to bring Bulgaria's nascent Christianity under their authority meant that heretical groups may have appeared to the pagan Slavs as just another version of Christianity vying for their loyalty. One of these groups were the Paulicians, another dualist sect. In the 970s, the Paulicians were relocated in massive numbers to Plovdiv, where it's thought they may have had some influence on the burgeoning Bogomils. The Paulicians were dualists, but unlike the Bogomils, they were not ascetical at all. Instead, the strict asceticism of the Bogomils was probably influenced by the monastic reforms sweeping through some Orthodox monasteries.

As Christianity was relatively new to Bulgaria, the Orthodox priests there were determined to stamp out any signs of heterodoxy in their newly converted province. Our first recorded opponent of the Bogomils was the writer known as Cosmas the Priest, who decried the Bogomils in his Sermon Against the Heretics. We don't know where exactly in Bulgaria Cosmas was writing this treatise, but he was evidently quite familiar with Bogomil beliefs and teachings, probably from talking to ex-Bogomils and from reading their books. What concerned writers like Cosmas so much was that the Bogomils were good at hiding their beliefs. Their clergy dressed just like Orthodox monks and nuns, and they taught their lay followers to lie about their beliefs if questioned. Only those who had been initiated into Bogomil teachings were allowed to discuss them freely. What originated as a survival tactic due to fear of persecution was construed by the Orthodox authorities as an attempt to secretly infiltrate their ranks and poison the Church towards heresy. Indeed, Cosmas goes even further than that, accusing the Bogomils of teaching their followers to hate the Tsar and that serfs should disobey their masters. Whether the Bogomils were really such anti-government radicals is hard to say; the accusation does not appear in later texts about them, so it was either a paranoid imagining of Cosmas, or something that characterized the early movement but faded away as it became more established.

Among the many charges Cosmas makes against the Bogomils, one stands out to the reader interested in women's history:

The heretics practise confession to one another and loose sins when they are themselves caught in the toils of devils. It is not just the men who do this, but the women as well, which is worthy of condemnation. For the apostle says, 'I permit no woman to teach or have authority over men; she is to keep silent.'

Laypeople were not permitted to hear and absolve confession, a rite that was becoming increasingly more important in the Church in this period. Interestingly though, abbesses were allowed to hear their nuns' confessions - and we know from other sources that the Bogomil female clergy called themselves abbesses just as the men called themselves abbots. The Orthodox clergy considered the title of "abbess" for a Bogomil woman to be illegitimate, but the Bogomils themselves clearly had a different idea. From their point of view, they were not deviating from standard practice by having "abbesses" hear confession.

In the centuries that follow, we have some extended treatments of Bogomil ideology and practice from Byzantine commentators, but the line from Cosmas the Priest is one of only precious few reference to the role of women in their movement. One comes from Anna Comnene, the daughter of Emperor Alexios I and a distinguished Byzantine historian. Writing of how her father executed a Bogomil priest around the turn of the 12th century, she wrote that his closest followers included twelve male apostles and "women of depraved and evil character". A 13th century Serbian text, the Nomocanon of St Sava, says that the Bogomils "appointed the women as teachers of the dogmas of their heresy, simply ordering them not to be the heads only of the ordinary people, but also to command with the priests". A 14th century nun called Irene is the only named Bogomil woman known to history. She housed monks from the monastery of Mount Athos when they came to visit her in Thessalonica, where she secretly instructed them in Bogomil theology, thereby exposing the holiest monastery of Orthodox Christianity to Bogomilism.

From these scattered references across the centuries, an image emerges of a movement where women could hold places of significant influence and importance. Whether there was truly equality for Bogomil men and women, as some scholars have claimed, is another matter. Other than the 14th century nun Irene, all of the Bogomil leaders whose names are known to history are men. The contempt for procreation and for children that the Bogomil elite held may have manifested in misogynistic ways against some mothers, although we can only speculate about this. What is clear, though, is that women did have an important role to play in the Bogomil movement. Fiercely critical of the wealth and corruption of the mainstream Church, women as well as men chose to disobey the strictures of Orthodox Christianity and forge a different path, one which they saw as being more in line with the lifestyle of simplicity and poverty set out in Acts of the Apostles.

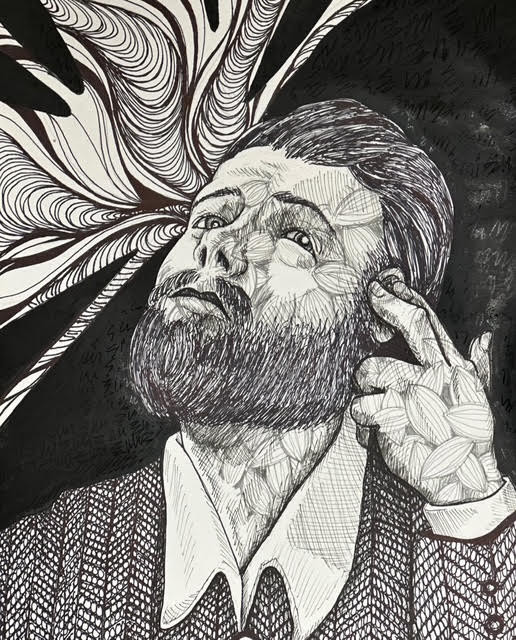

In this illustration, I have depicted a Bogomil woman being initiated into the Bogomil elite, often known as "perfects". The Bogomils recognised no earthly hierarchies except their own. There were three levels of Bogomil initiation: follower, believer, and perfect. To pass from one stage to another, a person went through a period of fasting, confession, prayer, and study, before experiencing what the Bogomils called baptism of the Holy Spirit. At the first stage, when going from follower to believer, the initiate faces west to renounce the Devil. When becoming a perfect, they face east to affirm God. This latter ritual can only occur when both men and women have testified to the initiate's enthusiasm for their way of life. Once they have vouched for the initiate's reputation, they gather together for the baptism. The Bogomils called an assembly of believers "Bethlehem" because, through their preaching and prayer, they gave birth to the Word (i.e. Christ) - for this reason they called themselves, rather than Mary, the Mothers of God. At a baptism assembly, the initiate had the Gospel of John placed on their head. The perfect holding the book would read out the first line of the Gospel of John: "In the beginning was the Word." Then, all of the men and women present would chant the "Our Father" and place their hands on the initiate. The baptism ended with a hymn of thanksgiving. And with that, the initiate was now a perfect, ready to live a life of fasting and continence and to teach the Bogomil version of Christian truth.

In this period, Christianity across Europe was starting to restrict ordained roles for women , but women's spiritual movements abounded regardless. Some of these were able to fit into established Christianity, such as the women who followed Clare of Assisi in the 13th century by becoming the Poor Clares. Others, like the women who became Bogomils, felt they could not express their faith within the confines of Orthodoxy, and so they turned to heresy instead. Most of these women's names are lost to history, and some of them were killed for their faith. But by telling the story of the Bogomils, we can commemorate the great risks they took in daring to live a life guided by values other than what the established Church accepted. Regardless of what their opponents said, they believed that they were radically committed to Christ and were willing to stick to that belief even at the cost of their lives.

Hooray for heresy! It's so cool to explore radical dissent in the Middle Ages. Mainstream Christianity had plenty of diverse and interesting women too, but there is just something so fascinating about women who joined heretical groups. I tried something different with the lighting in this one, with the direction of light coming from below. Like heresy itself, the symbolism of this depends on your point of view. Are they being illuminated by the fires of hell rather than the light of heaven? Or are they simply trying to conceal themselves from the bright glare of Orthodox persecution? It was fun to make a spookier picture as we approach autumn, my favourite season. For some reason the writeup for this one was really hard to write, but I hope you enjoyed reading about the Bogomils. I sure enjoyed learning about them! And I didn't even get into some of the craziest stuff, like Satan losing his god powers after turning into a snake to get jiggy with Eve...

Thanks to norree and SachiiA for help with this picture! This was somehow only my first Slavic entry in the series, and only the second in eastern Europe. It was challenging getting back into the groove of drawing after spending July in Shetland for my PhD fieldwork. But it's good to be back to Women of 1000!

Learn more on the website: womenof1000ad.weebly.com/heret…

Others in the series include...

Sembiyan Mahādevi and Kundavai Pirāttiyār

The Parishioner of North Elmham

Zoë and Theodora Porphyrogenita

Lady Yeli, Lady Wang, and the Yicheng Princess

Related content

Comments: 5

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 1 ⏩: 1

👍: 1 ⏩: 0