HOME | DD

Goliath-Maps — The Demography Debates: Syrian Political Parties

Goliath-Maps — The Demography Debates: Syrian Political Parties

#design #future #logos #middleeast #middleeastern #political #politicalsatire #syria #worldbuilding

Published: 2021-06-27 20:36:45 +0000 UTC; Views: 6635; Favourites: 19; Downloads: 0

Redirect to original

Description

Between the long civil war, the Levantine COVID variant, and the more-than-thirty-year Turkish occupation, and sporadic troubles up to the present day, Syria has not had a pleasant century. In its present state, Syria has one of the lowest human development indexes in the Middle East and a population smaller than Israel’s, divided by religion, ethnicity, and (recently formed) conglomerates [1]. Nevertheless, Syria is at last united under a democratic government with some respect for human rights (up to a point) and a new generation of leaders ready to consolidate the nation’s success.

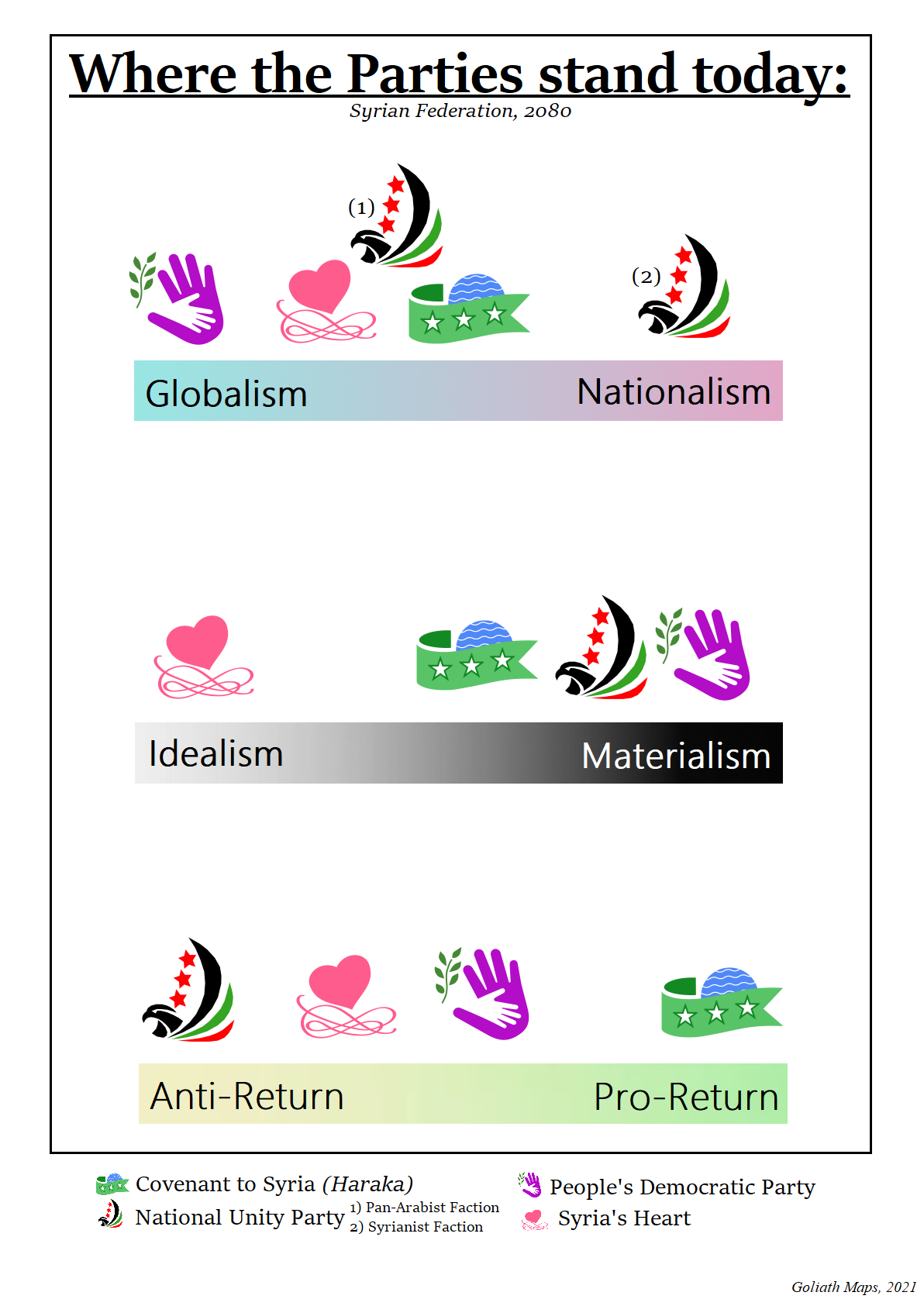

What should Syria’s role in the world be? Since roughly the middle of the 21st century, the parties have been clearly divided along ‘Nationalist’ and ‘Globalist’ lines, with the former defending the primacy of national sovereignty, often to promote economic equality and social cohesion, and the latter arguing that primacy of the nation impedes collective responses to major issues like climate change or the free movement of people and commerce across the world.

What should the individual’s role in Syria be? Another division is between ‘Political Idealists’ and ‘Political Materialists.’ The former see politics as primarily an exercise in morality and argue that people should organize around universal values or abstract ideals, which are sometimes religious in nature. The latter view politics as an exercise in distributing resources and satisfying the material interests of different groups, arguing that vulnerable populations can only be helped by self-interest.

Should Syria embrace returnees? Across the world, more people identifying as Syrian live outside of Syria than inside, with members of this diaspora often wealthier and more educated than Syrians living in the old country. ‘Pro-Return’ thinkers hold that all descendants of such refugees should be enticed to ‘return’ home to support the nation with a growing economy, improved living standards, and a shared project for cohesive national identity. Opponents argue that Syria does not have the resources (financial or spatial) to attract and house such migrants and that – more to the point – such demographic change will in fact re-open old war wounds. The most extreme ‘Anti-Return’ Syrians see moves to return as overcrowding the country with millions of culturally alien people who are no longer recognizably Syrian, or who, at the very least, upset the country’s new demographic balance [2].

….

Since the (latest) end of Turkish rule, Syria has been alternately led by two big-tent parties: The Covenant to Syria (Haraka) and the National Unity Party. These parties are similar in many respects: both are avowed secularists (although National Unity is a bit more skeptical of public displays of religion, such as the hijab), both eschew clear labels as either Globalists or Nationalists (National Unity is internally divided in this regard, while Haraka officially rejects the excesses of both Globalism and Nationalism), and both parties occasionally display some authoritarian instincts. Where the parties differ profoundly is in their bases of support: Haraka draws support from businesses, new returnee groups, and rural Sunnis, while National Unity draws support from the descendants of those loyal to the Assad regime and Rojava Kurds who felt betrayed by the west and fleeing Syrians. As a result, while Haraka is a strong supporter of ‘the return,’ National Unity is strongly opposed.

The third largest party, a leftover from when Syria was governed as Turkish provinces, is the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), also known by its Turkish acronym ‘HDP.’ Originally drawing most of support from Kurdish populations, during the 5th Iraq war, the PDP transformed into the nexus of underground resistance against the government of Turkey. Like its sister parties in other Middle Eastern and European nations, the Syrian PDP synthesizes an extreme Globalist views with extreme Materialist ones, calling for ‘international anarchy’ (the abolition of all governing states) as well as ‘social anarchy’ (self-determination of all individuals and communities achieved by ‘deconstructing’ social hierarchies). Despite their anarchist predilections, the PDP’s hard embrace of open borders and free trade means although they consider themselves to be ‘social anarchists’ they are not socialists and are in fact big supporters of capitalist markets. [3] Were the PDP to gain power in Syria, it would likely attempt to abolish national borders with Iraq and Lebanon, which are already under PDP governments.

The newest political party, Syria’s Heart, is an Islamist and Ummah-Globalist party founded by a famous social media streamer turned self-declared cleric. The party calls for a “sharia-inspired” international legal framework to replace national sovereignty, but draws a sharp contrast between itself and the violent jihadist groups of the past in declaring that “the shared love of Allah (exists) in all religions” and joining inter-faith dialogues (though these most often take the form of online debates).

[1] Networks of (competing) gated and heavily defended communities, usually infused with Chinese, Indian or other Arab corporate cash, where residents can have their own schools, hospitals, etc. without having to venture outside.

[2] Most returnees are more secular than current residents and more more likely to be Sunnis (at least nominally or culturally). Due to forced demographic changes, Syria is now only 50% Sunni, with the other 50% of the population (mainly Alevite Muslims, Christian, Shia Muslims, Druze, and Neo-Zoroastrians) usually opposed to efforts to raise the Sunni share of the population.

[3] Unlike social status stemming from wealth, the PDP recognizes differences in wealth accumulation itself as material and thus real. So, although the social existence of the wealthy as a distinct, superior social class must be abolished, PDP ideologues see no reason to abolish private capital-creation entirely. While outwardly appearing radical, this ideology is less radical the deeper you get into it.