HOME | DD

Jdailey1991 — Appetizing Arthropods, GLE, Art by AlienOffspring

Jdailey1991 — Appetizing Arthropods, GLE, Art by AlienOffspring

Published: 2022-02-08 00:21:52 +0000 UTC; Views: 18249; Favourites: 118; Downloads: 0

Redirect to original

Description

What animals have we humans physically and genetically altered to eat? An awful lot, including those we don't often regard as livestock (the dogs of China bring to mind.) This has enormous consequences that are of environmental concern. 51 million square kilometers of land--half of all the continents of the world--have been relegated for agricultural use. Of that number, 40 million square kilometers of land had been reserved for livestock. By contrast, another 11 million square kilometers of farmland were made to feed just us.

This is damning in so many ways. Never mind the fact that humans had bred out the intelligence that the livestock would need to defend themselves from predators and other natural threats, they require so much energy that they make up 14.5% of the blame for the current climate crisis. There have been many solutions brought up in recent years, one of which being a transition from eating meat to eating insects. This graph clearly demonstrates why.

Whereas most peoples outside the Western world have been eating insects for generations, we have found evidence that insect consumption has been a staple of xenosimian behavior for 53 million years. Many "monkey" species have endured the freezing winters of temperate latitudes and high altitudes by mining through rotten wood for grub gold. We have found palaeoarchaeological evidence suggesting that this talent had not been lost on the genus Draculodon. Certain populations of dwarves had farmed certain species of insects thousands of years before domesticating the gnoll and the golden warg into the hyena and the dog. Insects alone made up 35% of the proteins found in the form of isotopes within the teeth and bones of dwarves, with meat making up 25%, other arthropods 11%, fish nine percent and the remaining rest nuts and eggs. In elves, meat makes up only nine percent of the proteins, with insects still taking the top at 55%. Between them are 16% other arthropods, 18% fish and the remaining two being nuts and eggs. It would seem that elves and dwarves were far happier at eating bugs than we modern humans.

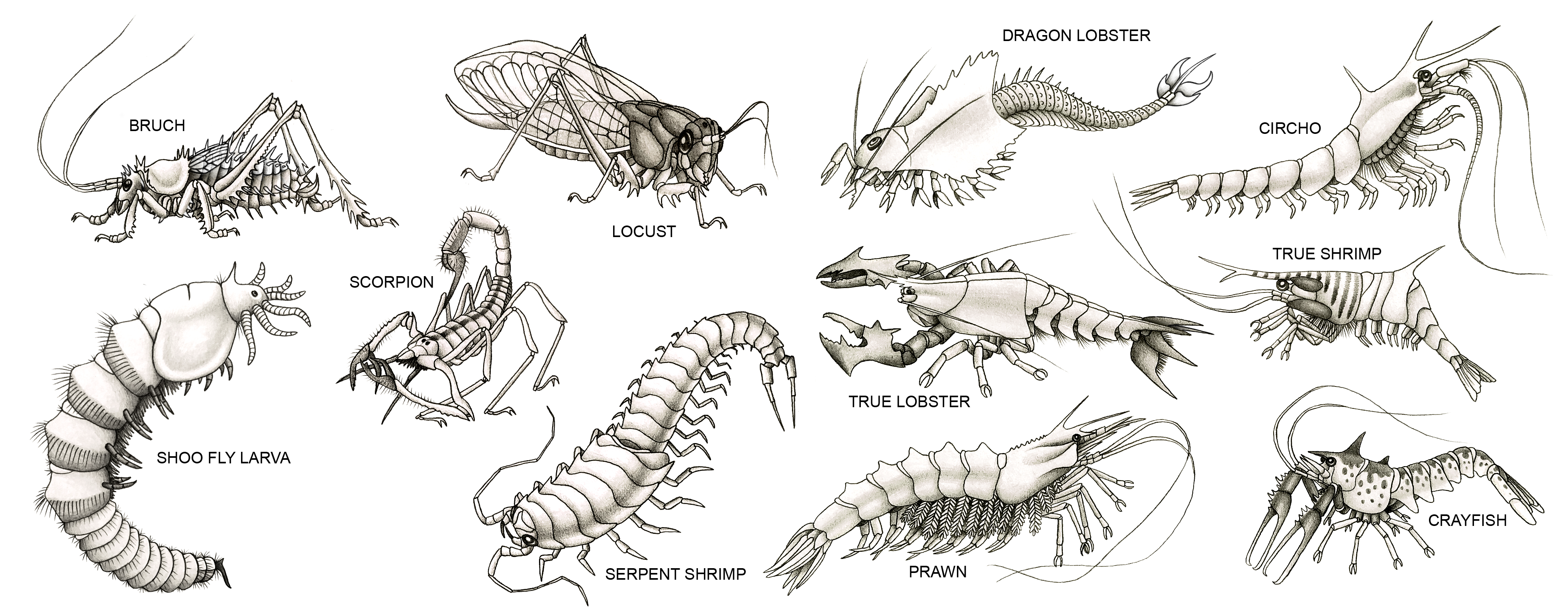

Indeed, lots of insect species have been domesticated and tamed (not the same thing) by the elves of Great Lakes Earth. Among them are the bruchs, seven families totaling up to 70 genera and 5,252 species of crickets in a world sans mice, voles, hamsters and guinea pigs. Whereas the similar-looking wētā can still be found on the islands of New Zealand, the bruchs can be found on six of the seven continents. They are generalists, scavenging on dead meat, rotting wood and moldy fruit. They are predators, hunting for worms and smaller insects. They are vegetarians, munching on soft, tender leaves. They are so low on the food web that their exoskeletons come extra with sharp, cactus-like spikes. (However, very patient predators will wait around for newly molted bruchs.) They are even long-living, with an average lifespan of eight years.

In temperate climates, the bruchs work their seasons like clockwork. In spring, with very little food on offer, they spend that time instead on searching for mates. The females use their small wings to advertise for mates, whereas the smaller males use their larger wings to fly around in great distances. Each wingbeat exerts a piece of the heat that the male would need to fly in the cold spring air. He wafts the air on his long antennae, looking for the scent of a female. He can mate with dozens of females from the first day of spring to the final day of spring, for the summer solstice marks yet another change. Starting at the summer solstice and ending right on the final day, the female bruchs spend the entire season feasting on whatever suits the fancies of both them and their unborn eggs. By the autumn equinox, they'd have tripled in size. (For the largest species, the German fisherman bruch, that would mean ballooning from nine ounces to 30 in just three short months.) In the autumn, the females' voracious appetites have not waned, feasting on fruits and berries that ripen in that season. But autumn is primarily laying season, and the females will dig several burrows underground or on treeholes, each one being filled with as much as 500 eggs. When the biting cold of winter comes and there is no food left for the bruchs, they do the one thing they share with the New Zealand mascots--they freeze themselves solid. This is hardly unique, as many ectotherms on Earth and all alternate Earths have used this same sort of suicide-looking adaptation against the hardships of winter. When spring comes back, the adults thaw out and their young hatch into miniature lookalikes. Because of the cold, the nymphs stay underground, hunting around for earthworms or legless lizards, which they would overwhelm together like wolves surrounding bison. Come the summer, they come out to feast on whatever meets their fancies, including adult bruchs. The nymphs would have to reach adulthood before winter comes, for babies don't have what it takes to survive freezing. This voracious, diverse appetite over the seasons and quick maturity may explain why some European species, like the German fisherman, have been farmed so intensively over thousands of years.

Among the fly order, Diptera, 86 species consist of one of the families of fungus gnats, Ditomyiidae. 17 species from both Europe and North America consist of one genus, the "shoo flies". They are the biggest of Great Lakes Earth's flies, closer in size to a grasshopper than an ordinary fly. One species in particular, the apple-pan dowdy shoo fly of northeastern North America, can spend one week of the summer egg-laying, each day witnessing as much as 500 eggs crowding the ponds and lakes. The maggots can spend as much as five years underwater, hunting for smaller insect larvae and mating with each other. It may seem odd that a baby would be fertile enough to carry eggs, but this is actually a strategy to cut the work off the adults, who have one week to find a different, suitable pond, lay their eggs and then die. That one adult can lay 3500 eggs is amazing, but it's the larva's abilities to get pregnant that makes them so appealing--all the better to get that extra protein. They are used most often used for baking bread and pastries for the same reason we humans use eggs on them--structure, richness, color and flavor.

The locusts of Great Lakes Earth are not the same as back home. Instead, they are grasshoppers that have taken the role of "mass noisemaker" since the cicadas died out during the Miocene-Pleistocene Cold Snap 14 million years ago, one of the very few insect groups that had become too specialized to stand the cold at all. There are 123 species of locusts all over Laurasia, and all are incredibly noisy. The loudest is a North American species, in which each male rings in at 96 decibels--as loud as Times Square! They have never been domesticated, for they spend way too much time as nymphs, where many species can spend 13 years of their childhoods underground. But after 13 years, they come out en masse to molt into adults. Once there, they have, depending on the species, from three days to one whole month, to find a mate, lay their eggs and die. A swarm can measure in at 40 to 80 million metric tons' worth of adults, switching their dietary preferences from root fluids to male locusts. A husband is just the meal the female needs to overstimulate fertilization. But during those three days, whole communities of elves can spend each day netting as much of them as they can. Afterwards, the caught locusts can be eaten in countless ways, even raw. Because different species develop in different prime numbers of years (from three to 19), these megaswarms are actually annual all across Laurasia (biannual in some years!)

Insects aren't the only arthropods to be farmed by the elves, though. Scorpions are popular dishes as well. One of the target species is the six-legged scorpion of southern Asia. It's called that way because the first pair of legs has been modified into sensors to detect the moistness of the soil beneath. If it's moist enough, then it'll prompt the male to build a simple bower of mud and moss to impress any passing female. In turn, the right kind of moistness is crucial for the female to dig her burrow and give birth in privacy. The six-legged scorpion is suited for farming because, unusual among scorpions, it's a pack hunter. A single scorpion doesn't have enough power in its stinger to penetrate the spiky armor of a bruch or in its claws to hold off a dragonfly, but a group of them will, earning them the second, more often used vernacular, "wolf scorpion". A single female can have as much as 47 nymphs that can mature in only three months. Immediately afterwards, the female can mate again and have another brood of babies. And, like most scorpions, the mother is fiercely protective of her young.

Like us humans, elves have fished and farmed crustaceans for their meat and also their eggs. Lobsters, crayfish, prawns and even shrimps have been farmed for centuries. Indeed, we have listed as much as 11% of the whole of Crustacea being domesticated for food purposes by the elves. Crabs, curiously, have never been domesticated or even farmed, maybe because of their aggressive temperaments, sharp armor and more-than-formidable claws! In their place are crustaceans unique to Great Lakes Earth. During the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, a freshwater species of isopod had found that it could work part-time on land and in water. This unknown species was the ancestor of today's "serpent shrimps". Many of them still live in lakes and streams in the tropics, but virtually nowhere else. On Great Lakes Earth, millipedes and centipedes are rare in the tropics but make up common, important keystones in temperate latitudes. Fairy tale woods in Europe are scary enough back home, but giant centipedes, especially those big enough to tackle snakes, are just one of the reasons why they'd be scarier on Great Lakes Earth. Many species of serpent shrimps are also big enough to tackle snakes (the largest species measuring in at 18 inches), but they avoid direct competition with chordate predators by laying poisonous eggs. Adults are essentially sacrificial lambs, allowing themselves to get eaten so that their babies won't. Numbers vary between species, but the mean average for a female to lay is 300.

Dragon lobsters, actually branchiopods most closely related to fairy shrimps, live similar lives, but some terrestrial species can be found in deserts and even tundra, bullying over their centipede and scorpion competitors like bears bullying wolves back home. The largest of these species is the Sonoran skullcrawler, a total landlubber as big as an American lobster. Named for their pale carapaces, useful in reflecting the hot desert sun, this is a parasite. Any reptile or amphibian unfortunate enough to come close to a skullcrawler gets an injection of neurotoxic venom from the crustacean's stinger. The stinger doubles as an ovipositor, injecting the eggs into the belly of the prey, paralyzed but still breathing. An hour or two later, the venom will wear off and the victim gets back to business as usual. But for the next week, the eggs within the body alter the carrier's hormones, forcing it to eat more. This change in behavior is to feed the babies developing inside. Before long, the babies start eating the meat of their own host. What a horrible way to go...Many skullcrawlers around the world are also parasites, but most don't get any bigger than prawns. One species of dragon lobster in southern Asia has been domesticated for their docile, vegetarian natures. The naga dragon lobster, as it's come to be called, is the size of a rabbit and munches on algae and mosses that would be deemed detrimental to any fruit crops. It's for this that they have been domesticated, though thousands of years of trial and error result in their domesticated forms laying more eggs more often than their wild forms--ballooning from 210 eggs to 250.

The circho is a terrestrial relation of the krill. Odd, but 50 million years of evolution can result in multiple paths that eventually accumulated to the life of a circho. In so many ways, they live their lives like aphids do. In the spring, the larvae hatch far more developed than marine crustaceans. They spend the spring underground, feasting on earthworms and the fruiting bodies of fungi. Along the way, they find males to mate with and soon afterwards lay as much as 30,000 eggs. Once summer comes, the circhos molt into a new form, one that requires getting off the surface and spending a living hunting the undergrowth for slugs and caterpillars. Along the way, they find males to mate with and soon afterwards lay as much as 30,000 eggs. As summer is replaced by autumn, the circhos molt again into yet another form, one better suited for feasting on leaves and bark. Along the way, they find males to mate with and soon afterwards lay as much as 30,000 eggs. Before the winter solstice comes, the adults die.

Edible arthropods are a literally palatable watershed in elvish culture. So why had so many species of reptiles, birds and mammals been hunted for their meat? Blame the Hannen for this. They had already domesticated puakas and tatankas centuries earlier, but they had also domesticated insects and other arthropods. By the reign of the White Dragon in the first century CEIHY (Common Era In Human Years), arthropods no longer showed up on their menu. Why? Perhaps it was because, as the White Dragon dramatically shifted Hannen from a center of culture into a hypertoxic, shut-off and militant patriarchy, they seemed to be preferring quantity than quality. A bug would be too tiny to feed one elvish soldier. So the meat of larger birds and mammals was more appealing and easier to grasp. As a consequence, 12% of the wild lands within the borders of the empire had been lost to farmland. This seems very concerning, particularly when other cultures around the world domesticated different animals for different purposes. Europe, Africa and the Americas had retained the originally Hannen invention of extracting silk from the eggsacs of cityspiders, and several different species of ungulates had been domesticated for their tusks, their horns, their manure, for lawn mowing, for weed control, for their milk, for plowing, for draft, for mounting and for their hairs, but only the puaka, a piglike elephant, had been domesticated for their meat. The European bonnacon gets sheared every spring so that the elves could make, sell and buy their qiviut. Camel-like macraucheniids were used for similar jobs, but they get sheared for a different kind of coat, shahtoosh. Dogs descended from the golden warg are retrievers, sighthounds, pointers, setters and spaniels, whereas hyenas descended from the gnoll are scenthounds, mastiffs, pinschers and schnauzers. Hamsas were the only birds to be domesticated for their eggs. The rukh has also been domesticated to assist the dogs and hyenas in multitasking companionship. The rusty enfield, a smaller, more omnivorous relation of the golden warg, has been domesticated to be part cat, part terrier.

It is only recently that arthropod agriculture had undergone a radical resurgence in popularity. Once the elves realized how much harm the Hannen method of agriculture was causing on the planet, mammal factory farming was banned, forcing many farmers to move their herds to the extraterrestrial colonies, like the domes of Mars, the underground cities of Mercury or the Bernal spheres, O'Neill cylinders and Stanford toruses orbiting the bulk of the solar system from Venus to Saturn, expanding the elvish population to 61 billion.

Related content

Comments: 18

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 3 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 3 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 3 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 2 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 1 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 0