HOME | DD

Mobiyuz — Land of the Setting Sun

Mobiyuz — Land of the Setting Sun

#alternatehistory #california #fusang #alternatehistorymap

Published: 2024-04-22 05:41:24 +0000 UTC; Views: 14460; Favourites: 117; Downloads: 18

Redirect to original

Description

I did a Fusang map a very long while ago. Let's take another crack at it.

---

Despite counting among the world's most powerful civilizations throughout all of history, China is historically not known to have been a major naval power. To a large extent, the zenith of China's pre-modern naval prowess was the voyages of Zheng He, and even that was more for the technical achievements of his ships than anything else. Although his "exploration" was along known routes to known locations, the ships were stunning marvels of engineering, able to bring thousands of crew around half the world. And yet, China was so confident of itself that the Hongxi and Xuande Emperors not only stopped the voyages but disposed of most of the records of the voyages, deeming them unnecessary. Yet one anecdote did survive: a rather odd incident, where supposedly four ships were stolen by opponents of the Ming and taken east to discover Fusang, whereupon they would return to liberate China from their insular rulers and return China to an open place in the world. Nothing more was ever spoken of them, and for 200 years no one thought much of it.

The arrival of Europeans to the New World brought surprises in all forms, not least their existence of course but also a number of new plants, animals, and cultures of people who to most extents had no knowledge of the Eurasian world. At the same time, though, there were irregularities, things that resembled Chinese artifacts which led many to suppose that perhaps this new world did have a connection to or easy route to China, the true goal of most explorers until the wealth of the New World was properly understood. Helping this was that the further west into this land that they went, the more they found evidence of clearly Chinese things: tools, writings, even animals that were described by most as being new to their lands even before the Europeans had brought them. And then Cortés himself met a Chinese man when his soldiers entered Tenochtitlan, or at the very least someone who looked Chinese and sounded Chinese, who said he was a trader from the north. It didn't stop him from conquering the Aztec Empire when he could, but the moment that was completed he immediately looked beyond.

Disappointingly, what Cortés found wasn't China. It was far, far stranger and perhaps more fascinating, a place that resembled China but which wasn't, and which had been seemingly divorced from China for centuries. It was a strange place and yet familiar all at once, at least for those familiar with China itself. At first, the European reports led some to believe that China had somehow beaten Europe to the New World, but only with the later rise of a more holistic understanding of human history did it become apparent. Although the anecdote of the "flight of the dissidents" had been discounted by almost everyone who heard it, that a distinctly Chinese civilization suddenly appeared in western Hesperia around the time of the Xuande Emperor's reign ties neatly into a feature of the Pacific Ocean: the North Pacific Current, a vast current which flows from East Asia across to Hesperia and which joins the Fusang Current off the coast of the Damen Strait, which provides a convenient means of helping to explain how the ships would have crossed the ocean and landed where they did.

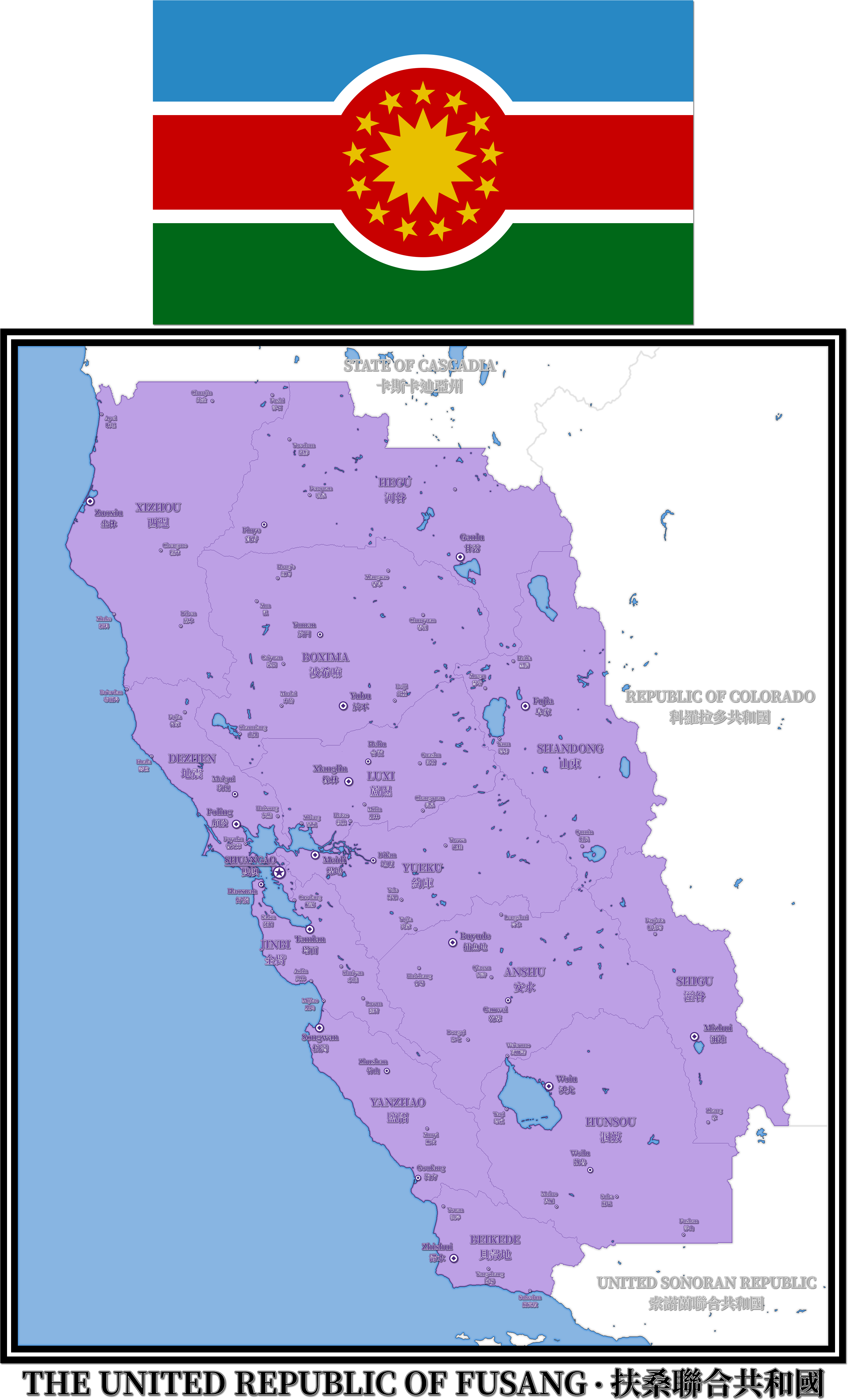

Whatever the exact nature of their arrival, the Fusang met by Europeans was in some ways a sort of tangential society to China. Although its inhabitants spoke of there being one "Great Fusang" (大扶桑), the "country" was instead a motley assortment of city-states and petty kingdoms that largely obeyed their own laws which, while still derived from the same kind of law codes that had been implemented by the Ming, often diverged strongly from place to place. Importantly, all of the major core settlements bore an allegiance to the city of Shuangao, which most held in the same position that Nanjing and later Beijing held in China proper. As many sources from the time describe an "Emperor of Fusang" as much as an "Emperor of Shuangao", at times vastly diverging in describing exactly how much power the supposedly central authority held in the country. As if to further underscore this uncertainty, by and large the "Emperor" wasn't even a hereditary position at all, making the actual political structure relatively difficult to understand even for the Fusangese.

For the most part, an understanding of contemporary records and outside observations when brought together seems to describe a state akin to the Warring States period overlaid onto the Holy Roman Empire, though considerably more peaceful than such a situation sounds. Conflict certainly did exist, of course, and many generals often skirmished in efforts to claim settlements and territory for themselves, leaving the whole country in a very politically fluid situation. Yet just as often, warlords traded and negotiated with each other, even arranging diplomatic marriages and at times negotiating with European powers and native Hesperian nations independently from what the "Emperor" declared to be national policy. In a number of ways, the "country" was a quasi-anarchic confederacy, one that almost defies categorization and yet one which repeatedly resisted European encroachment. If nothing else could bring the jockeying powers of Fusang together, attempts by Spain, France, Britain, and Russia certainly could.

Importantly though, this society was Chinese in its origins but not truly "Chinese" in appearance and practice. Although the elites had come from those Chinese who came on the boats and who carried their ideals of Huaxia supremacy with them, they likely numbered only 4,000 at most, and through both political negotiation, personal interest, and in many instances forced assimilation the Fusangese had become an ethnically distinct people that were effectively a mestizo culture between Native Fusangese and Han Chinese, so much so that when the Ming were later made aware of Fusang's existence they dismissed it as being "non-Chinese", which despite its language, culture, and history, wasn't an incorrect observation. The longer that Fusang had been divorced from China and in greater contact with the native Hesperians, the more that the country ceased to be "Chinese" and was instead "Fusangese", something that would only become increasingly relevant in the century to come.

In the mid-17th Century, China was conquered by the Manchu, who declared the rise of the Qing Dynasty. Fusang drifted ever-further from the core of Huaxia in those days, with many starting to see theirs as a liberated China. The sentiment wasn't lost on the Qing, who repeatedly schemed to potentially cross the ocean and invade Fusang to make it a proper colony akin to New Spain or Brazil. Of course, the Qing were even less of a naval power than the Ming, and even when the Dynasty reached the apex of its power in the early 1700s there was little chance for such a venture, not least for the fact that by that time Fusang had undergone its own period of consolidation. In 1701, as Europe was torn by the War of the French Succession and the Kangxi Emperor had enshrined his authority, the assassination of the Huozhi "Emperor" had kickstarted a major political crisis-cum-civil war which culminated in the almighty Battle of Seven Generals, in which time 90% of the city of Shuangao was destroyed and all but one of the generals was killed.

It was in this climate that the seventh general, a Sinicized Yokoch named Wa Huqia (likely a Sinicization of the name Wahumchah) was able to assert himself as victor by default, and gained the allegiance of the six rival armies by promising not to have them purged if they swore loyalty. With all his rivals effectively eliminated, Wa was able to assert himself as the leader of a unified Fusangese government that was able to press back outwards against the Spanish, British, and Russian colonial forces to consolidate power on a number of disputed frontiers. Declaring "The mountains will be our new Great Wall", Fusang pushed its effective borders into the mountains surrounding the Henghe Valley, beginning a prolonged period of internal peace that allowed Fusang to consolidate power, rebuild Shuangao as a properly imperial city, and construct a new bureaucracy that held inspiration from both the ancient Confucian bureaucracy of the homeland as well as the emerging legislative democracy in Britain.

The rule of the Gongyi Emperor helped consolidate Fusang as a fully-realized nation rather than just a region in the western edge of Hesperia. As it consolidated, a national spirit had begun to take hold that diverged significantly from that of its homeland, as set amongst the colonial holdings of Europe the nation had to do something that China itself hadn't truly needed to do for centuries: compete. Although various dynasties rose and fell, and twice outsiders took command of the country, China as a concept was unchallenged for 4,000 years and had almost no existential threats prior to the dawn of the 19th Century. Fusang, far weaker and on much more tenuous footing, had no such luxury. If it was at some point conquered by some European power, it would likely be erased by a wave of European settlers whether or not the Fusangese themselves, their cities, and their legacy persisted. To this end, Fusang began to push to advance and develop, taking in new ideas at a far greater rate than Qing China.

If there was some point when Fusang surpassed China itself, it would likely have been in the year 1807. As Europe fell into the midst of the Spanish Revolution and the Alexandrine Wars, the Russian Empire was emboldened, and as Madrid's colonial empire collapsed Moscow saw an opportunity to expand her holdings. Operating from Fort Ivan outside of Kuala, the Russians leveraged their trade outpost to serve as a launching site for a broader invasion of Fusang. The Russians made significant progress, marching as far as Xianglin, but Fusang's navy overwhelmed the Russians at the Battle off Yisikai and destroyed their ability to resupply their forces. Unable to cross the Liutu Marshes, the Russians failed to put Shuangao under their guns, giving the Fusangese the capacity to begin pushing back against the Russian forces. In particular, a surprise amphibious assault against Xifeng caught the land-facing Russian defenses off-guard and in one battle destroyed 30% of the remaining Russian forces. The war ended with a status quo ante bellum, but for Fusang it was a titanic spiritual victory.

When Spain was finally defeated in 1817, Hesperia was left as a motley assortment of newly-independent colonies seeking to form nations (apart from the French colony of Canada, but that's a different story). Fusang stuck out for being a "non-colonial colony", an established nation with a past built upon colonial practices but which had long since emerged into a distinctive entity of its own. A flurry of treaties settled Fusang into its modern borders, giving the nation its current shape and helping to more closely integrate it into the international order, especially after its remarkable victory against the Russians. The Qing, meanwhile, had long since begun their decline and in the aftermath of the Amur War (1820-1822) that saw Russia grab at parts of Manchuria itself, Fusang seemed poised for a brighter future than China itself. True, it was far more mixed and "non-Chinese" than China even under Manchu rule, but it had proven able to stand against a European army even without the massive resources of China itself, and for that it was poised to stand against an increasingly Eurocentric world order.

Indeed, it would be in the 1800s that Fusang came into its own. Nationalism was slower to take root in some places, but Fusang had long since been in the beginning years of identifying itself as Fusangese (扶桑人) rather than Chinese, and the unique blend of Chinese and Native cultural customs, not to mention the broadly mixed ethnic character of the country, gave the country the ability to claim itself as a nation among nations rather than simply an extension of some larger power, much as was also the case in Europe. Alongside this, the country's population began to boom through both native population growth as well as a wave of Chinese immigration from the rapidly stagnating China, though this in and of itself led to its own troubles: Han Chinese often found Fusang an uncanny kind of place to live, recognizably similar to their homeland but different enough to make it difficult to adapt to. Others who migrated to places like Cascadia, Virginia, or Andea would often describe it as much easier to adapt and assimilate to those countries than to Fusang.

Not that everything was troubled, of course. If the 19th Century was the Century of Humiliation for China, it was the Century of Flourishing for Fusang. Rapid industrial progress, infrastructure development, and the expansion of farming across the Henghe Valley let Fusang soar ahead of many of its fellow Hesperian nations in almost every indice. Though of course, with progress comes uncertainty, and where social agitations simmered then exploded in China in Fusang they remained at a rolling boil for much of that time, frequently bringing great political strain to the country but never to the point of complete collapse. Political agitation frequently called for reform that seemed far more achievable than the wave of chaos that was inevitable in China, and people often took great inspiration from the emergent European ideologies of liberalism to argue for their causes. In fact, for all of that time there was only one military overthrow of the country's government, and in many ways it only needed the one.

After only a century of rule, the Wa Dynasty was already starting to show signs of decay, and many were calling for change as was often the cycle of the Mandate of Heaven. What made this movement different, though, was that the primary "flavor" of revolt was increasingly republican. Some argued that a democratic republic like that in Virginia or Norumbega was incompatible with Chinese culture, but here the shift from "Chinese" to "Fusangese" took full effect. In the eyes of the republicans, their country was not merely some extension of Huaxia. Cultures were not static, and after more than 500 years of separation from China theirs had evolved into something entirely new. Whether Chinese culture was compatible with democracy was a moot point, because they were now Fusangese, and the Fusangese were capable of adapting new ideas to meet their culture. Theirs was a dynamic and virile culture, and China itself had long since fallen prey to the same "barbarity" they had long accused other cultures of being beholden to.

To make matters worse, as industry took hold in the country the social shifts it produced upended the traditional social orders of the country as previously low-born men and women now had greater autonomy in life through being able to find new work in the booming cities, and in a number of cases rise to become titans of industries in their own right. With wealth and influence but continuing difficulty in actually entering the halls of power, increasingly people began to turn to the growing movement dubbing itself the Thirteeners. Taking its name from the 13 provinces of the country, the movement soon took on its own spirit by issuing a declaration of the Thirteen Guarantees of the People, creating what was thus dubbed the Shisan Doctrine (in some terms, "Triskaidekamism"). With support swelling among the people and rapidly taking hold in the military, on 17 April 1869 the country's generals staged a bloodless coup that interrupted and halted the enthronement of the Renxiang Emperor, instead declaring the monarchy to be at an end and declaring the United Republic of Fusang.

The formation of the Republic fully and finally severed Fusang's identity from being a mere extension of China. Under new government doctrines, the people ceased to call themselves Chinese and now fully adopted the term Fusangese, declaring that Fusang was not beholden to the concept of Huaxia. Many of the same cultural signifiers were kept in place, notably the Chinese syllabary, but Fusang would no longer see itself as Chinese any more than Virginia was English or Sonora was Spanish. There was now a distinct Fusangese nation, one which was a nation-state the like of any other cultural and national identity. The Shisan Revolution, despite how Qing propaganda initially framed it, was not the Thirteener government artificially engineering a Fusangese identity but rather the formalization of an identity that had already existed but which had been buried under a veil of being dubbed "Chinese" for more than a century. 1869 would thenceforth become Year 1 of the new Fusang Republican Calendar.

And it came not a moment too soon, because the same idea of national identity had been spiraling into a broader global conflict that had reached into China itself. When the Qing were finally brought down through the Jiwei Revolution, the same ideals of Triskaidekamism found little purchase in China with how thoroughly it had become identified with Fusangese national identity, and rather than the creation of a republic as might have been hoped in Fusang China instead found itself in the grip of yet another monarchy, albeit a Han-dominated one. The newly-declared Kai Dynasty (凱) began a rapid attempt to try and catch up with Europe, especially after the Turkestan War had seen China's westernmost territories seized by Russia, but dominant in their mind was Fusang. For some it was an insolent defiance of Huaxia, and the more that the Kai Dynasty fell into its paranoia and increasingly militant belief in the supremacy of Hua over Yi the more that high-ranking officials began to look at Fusang with venom and bile.

Not least for the fact that Fusang itself was doing extremely well for itself. With the largest national population in Hesperia, the largest economy, and a vibrant culture that was undergoing its own era of flourishing, the country had finally come into its own. The country's embrace of change and progress had led to it becoming a dynamic hub of innovation and progress. In many ways it was at the height of its power, something that was regarded with equal disdain and jealousy from neighboring states who all held their own complexes over Fusangese inferiority which stemmed from Europe's own racial biases and systems of discrimination. Not that it particularly mattered to Fusang, a country that had developed such a diverse community of immigrant cultures set amidst an equally diverse range of biomes and terrains that the spirit of the age was captured in the phrase "All the world under our flag" (全世界都在我們的旗幟下), which would ring deeply ironic in the decades to come.

The British general Walter Falkirk declared in the year 1900 "China is a dragon awoken, and her wrath will shake the world." It was a prescient observation, as by 1930 China had already been able to martial its resources and military power to such an extent that the smaller nations of Korea, Tibet, and Japan had been overwhelmed and brought under Chinese occupation, which were but the first stepping stones towards the "Declaration on the Restoration of Global Order", wherein the Chenhui Emperor declared that China would at last fulfill her mandate and "Bring the rebels to heel", where the "Rebels" were anyone and everyone who did not live under the rule of the Emperor. In practice it was a declaration of war on the entire world, something that Europe at first met with amusement that rapidly fell away when modernized Chinese army units began to march across Siberia and into Southeast Asia, overwhelming the European colonies with ease. What had once been thought to be a short war would drag on for nearly 20 years, plunging the world into the depths of the World War.

Such was the power of Chinese industrialization and modernization that at some point every continent and most of the world's sovereign nations suffered some form of attack by China during the war. For Fusang in particular it was a nightmare, as their country was the first to be directly targeted with a trans-oceanic invasion by the Kai Dynasty. The coast was rapidly overwhelmed, and although the Kai forces were soon bogged down in the country's many mountains the cities occupied by China were subjected to a vicious program of "Re-Sinicization". The Chinese did so for most any territory they occupied, but in Fusang it was a particularly focused effort. In the eyes of many historians, the Chinese had become obsessed with Fusang as an error within Huaxia that demanded to be corrected, and while the Chinese saw all outsiders as barbarians the Fusangese were worse, they were Han who had become barbarians and forsaken civilization, something deserving of the most intense and grueling punishment for the sin of having abandoned their true civilized world.

Even when the great cities of the coast had fallen, the Fusangese government continued to fight, in many cases slipping agents into Chinese concentration camps and launching mass revolts in the occupied zones. Even when Fusang's government operated out of the arid and isolated city of Mizhui, their military remained a primary fighting force on the western coast of Hesperia, and to this extent China's focus on "correcting" Fusang began to wear on their broader efforts on the continent, sapping resources from pragmatic operations in the name of dogmatic ideology. And while China was certainly powerful, an assault against the entire world was unsustainable even for them and their flotilla of collaborationist states and their plundering of foreign resources. Nearly 300,000,000 people died before the war's end, almost 2 million in Fusang alone (a whopping 10% of the country's entire population), and only when thirty Chinese cities were annihilated by fission bombs in the final attack known as "The Big One" did the guns at last fall silent across the world.

Humans are at times a stupid and forgetful species, but 20 years of war and the death of almost 15 percent of the entire global population, not to mention the Breaking of China that sent its population collapsing to a mere 40% of its pre-war size, brought humanity a level of reckoning unknown of before in history. Entered into that period of "never again" that follows every such major war, the world began the slow and painful process of rebuilding. Fusang for its part was utterly ravaged by war, something that in no small part helped to prompt the formation of the Hesperian Union to bring Fusang closer to its neighbors and turn the rebuilding process into a much more collaborative one. Hesperia for its part was a much easier place to accomplish this, as the European nations saw their empires fall away and their angered and upset populations turn on each other in the aftermath of the war. As one of the larger and more powerful nations even in ashes, Fusang was well-positioned to take a leading role in the rebuilding of Hesperia.

It also slowly began efforts to try and reconcile with the humbled and broken China, now shattered into six independent republics following the downfall of both the Kai Dynasty as well as the Mandate of Heaven. Although Fusang no longer saw itself as Chinese even when its culture and history had a clear connection, there was still some sympathy for the Chinese people themselves and as Fusangese food production recovered its titanic surplus began to make its way into China, helping to start easing tensions but still in the midst of an uphill battle to try and overcome the scars of the past. Some states like Fujian and Manchuria are repentant for their part in the war; rather infamously the State of Jiangsu is defiantly not. Worse still is that the lingering division between Hua and Yi remains in the minds of the Chinese, and even if many have admitted defeat some still refuse to accept that it was wrong. Fusang, for its part, has firmly placed itself into the Yi camp, something which still places it outside of what the Chinese consider familiar.

But Fusang for its part has recovered splendidly, even if there are periodic "echos" of lower birth rates from the loss of life during the war. While no longer Hesperia's most populous nation nor its most economically powerful, its efforts have long since shifted towards soft power and the dissemination of Fusangese popular culture around the world, something that the mighty media factories of Songwan have proven exceedingly efficient at. Fusang is just one nation among many, but it holds something of an outsized influence for the way it has been able to utilize every strength it has to accommodate for its weaknesses, and although the population has long since crested at 50 million and holds steady as of 2024 (Year 155 of the Republic) population growth is no longer treated as the metric that deems a nation as advancing. The age of growth is over for Fusang, now it is an age of optimization and ever-improving efficiency as the horrors of the World War begin to fade in the face of a world that, if far from utopian, certainly shows great promise.

Hurdles unnumbered remain in the path of that dream of a perfect world. Fusang for its part is acutely aware of this, as continuous years of drought exacerbate vicious wildfires that at times choke the great cities of the Twin Bays with so much smoke that merely going outside becomes hazardous to one's health. Wealth inequality is on the rise, driving the government to dramatic action that culminated in the 2019 "Equalization Payments" that issued a one-time tax on the country's wealthiest people to distribute massive amounts of money to the country's poorest, something that drove an immense number of business owners and affluent billionaires out of the country. But the effects were dramatic, with the economy surging ahead even when the world continues to languish in the eleventh year of the Great Depression. Although certainly disruptive, the positive outcomes have led many to demand a repeated effort at equalization, something that helps to continue to drive the once-sidelined ideology of Collectivism further into public support.

There has always been a desire for a better world, to start a better society. That was what the flight of the dissidents that had founded Fusang was meant to achieve, after all. And centuries on, in the 588th Year of Landing and the 155th Year of the Republic, Fusang still hasn't achieved that. It's certainly come much further than almost anything before it, at any rate, as has much of the world in general. Mortality is down, health is up in almost all metrics, and happiness (subjective as it is) is at an all-time high. All of it could come crashing down, of course, if any number of social or ecological issues can't be overcome. Humanity has reached an age when it can destroy itself, and whether that be all at once through the fires of nuclear bombs or slowly through the Anthropocene Extinction remains to be seen, if at all. Still, nations like Fusang are emblematic of the way many nations seek to try and overcome these hurdles, and if radical action is called for then Fusang has certainly shown that it is more than willing to do whatever is necessary to bring that golden path into being.

Related content

Comments: 25

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 1 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 1