HOME | DD

TrollMans — Maple White Land Biota (Spec Challenge)

TrollMans — Maple White Land Biota (Spec Challenge)

#lostworld2020

Published: 2020-10-02 20:56:56 +0000 UTC; Views: 142022; Favourites: 895; Downloads: 100

Redirect to original

Description

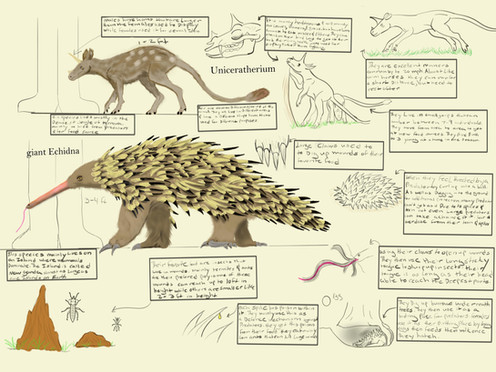

Knifeback Porcupine: A large spiny rodent species found throughout the Maple White Land, iwas initially considered a species of porcupine (hence the name), due to the long, spiny quills its possesses, but is actually a specialized spiny-rat (a closely related caviomorph group which similarly developed defensive hairs). However, this branch of insular spiny-rats have developed some of these spines into more flattened plates resembling overlapping scales; these are extremely similar in structure to the unrelated pangolins on the other side of the world (at the time of its discovery however, it was used as evidence to suggest pangolins may have evolved from rodents, purely on certain morphological similarities such as this). Adults primarily forage and nest on the ground due to their mass, but young knifebacks do not yet develop the scales and more closely resemble porcupines, including the ability to climb freely.

Weighing up to fifty-five kilograms, it is of substantial bulk, just exceeding the largest beavers in size and second only to the capybara among rodents, and its size is further exaggerated by the feature for which it gains its name, a row of particularly large and elongated erect plates and spines which run down its back and can be over four feet in height. These are utilized for display and communication among individuals and can be raised and folded down on command. As expected, the rest of their body is covered in shorter, but much sharper quills which serve an effective defensive purpose. When threatened, the animals will first raise their “sail” and shake their body to produce a rattling sound in an attempt to warn off predators, but if this fails they will swipe at them with their spiny tail, which is covered in sharp-edged plates and pointed quills. Any animal still persistent enough to get to this point will ultimately learn a very painful (and possibly final) lesson if they are struck by this tail, as the forceful swings will generally dislodge a large number of spines at once.

The species is polygamous, with males generally holding territories and maintaining small harems of females. Similar to other caviomorphs, the species breeds very slowly for a rodent and only has a single pup (or rarely, twins) per litter. However, this pup is relatively large and highly precocious, capable of feeding itself only hours after birth, but sticking close to its mother for up to a year. Males play little part in care of young, but may occasionally groom their offspring and remain close to mother and pup for periods to help defend it from predators. Young knifebacks are often known as “sailbacks” because instead of the jagged profile of their raised scales, they sport a mohawk-like row of highly elongated spines down their back (which aids adults in spotting them) that falls out before sexual maturity. Initially, it was not realized these were growth stages of the same species and were thought to be different, closely associated species for years, due to the extreme differences in colouration and integument.

The species is primarily herbivorous and can feed on a wide variety of vegetations, including bamboos, tubers, woody branches, and hard nuts, but will periodically supplement this with insects or eggs as a source of calcium and protein. Juveniles, able to climb into trees, are capable of consuming leaves and buds in a manner different from adult knifebacks, but all life stages are capable diggers to search for roots and starchy root vegetables, as their shape makes it difficult for them to fit into burrows.

Cobra Eel (Hooded Caecilian): An unusual amphibian species which slithers through the moist leaf litter and damp soil of the more forested regions, and unlike most caecilians, spends most of its life above ground and out of the water (although it is an adequate swimmer that will fish for aquatic prey at times), with the high permanent humidity of this particular environment permitting this. Almost totally blind, it primarily uses highly sensitive olfactory receptors (enhanced by fleshy facial projections) and detection of vibrations through its jaws to navigate and detect prey. It is camouflaged by a dull, mottled skin colour, and moves very slowly; if it detects strong vibrations through the earth that may denote footfall of a larger animal it will stop moving for several minutes to prevent predators from tracking it through movement.

If it detects the threat has not passed, the caecilian will raise its unusually flattened lower body to reveal colourful marks on the underside, both an aposematic warning and decoy that disguises the head. Uniquely among amphibians, it is actually venomous and is capable of defending itself through a painful bite that will inject its toxic saliva. The bladed, hooked teeth and powerful jaws will clamp down on anything that grabs it, and through a chewing action will stimulate the release of further venom from its gums to continue to pump the poison into the bite wound. These toxins are used purely for defence, as the amphibian otherwise only hunts very small prey that it can easily kill with the bite alone and swallowed whole, such as worms, ground-dwelling arthropods, and the occasional small vertebrate. Its heavily built jaws are easily capable of crushing the toughest exoskeletons of the crabs and ground beetles it may occasionally feed on. Human fatalities are unlikely, but the reptile or avian predators which may threaten the cobra eel can be killed by its bite. Only adult caecilians can produce venom, as unborn caecilians feed by tearing away their parent’s skin secretions inside the womb and this allows them to feed without accidentally envenomating their mother.

De Loy’s Sloth: One of the largest species of this isolated ecosystem as well as an example of insular gigantism. On the initial expedition, these were only seen from a distant due to their skittish personalities and misidentified as unusual spider monkeys. In truth, these are in fact the largest living sloths, weighing up to sixty-two kilograms in exceptionally large individuals. They forage mostly as night in small groups; unlike all other known sloth species, this is a semi-terrestrial species, equally at home on the ground or clambering above. While initially speculated this species may represent a transitional form of sorts between the huge ground sloths and the smaller and purely arboreal tree sloths, later studies indicate it is more likely a secondarily terrestrial descendant of tree-dwelling three-toed sloths and is not closely related to the extinct ground sloths.

On the ground, the sloths walk with a very similar posture to gorillas due to the their large claws and long arms. In truth, gorillas likely represent one of the closest analogues to the De Loy’s sloth, similarly being a group-living and primarily folivorous mammal, feeding from trees and shrubs and avoiding grasses and more fibrous vegetation. However, similarities are largely superficial; while the sloths do live in groups, these are loose associations at best and adults hold no social bonds between one another. They remain together for mutual protection; while adults can stand over five feet tall when standing upright and can defend themselves with strikes of their huge claws, they are slow and cannot flee from most threats. When a predator is spotted they will clump together to cover one another until the threat passes and they can re-disperse. During the day, they sleep in trees or in crevices on cliffs out of reach of the large saurian predators which are their primary enemies.

The shaggy hair of the sloths are a miniature ecosystem in and of themselves. It often becomes host to numerous minute commensals and parasites. Similar to tree sloths, small moths nest within their hair and often swarm around them at night. Microbats like to follow the herds of sloths to hunt these moths, and the other flying insects which pester the xenathrans constantly and in daylight hours, several species of insect-eating passerines may search among the fur for lice and ticks. A type of land-dwelling crab with a two-centimetre wide carapace lives almost exclusively within the fur of this sloth, feeding off of algae, insects, and dead skin, clambering about with hooked legs and a smooth carapace that is almost circular. One species of weevil lives almost entirely on its hair, feeding on seeds caught by its matted integument and depositing its eggs in the sloth’s dung.

Coloroo (South American Wallabies): Certainly one of the most unique Maple White Land denizens, these are bizarre mammalian meat-eaters, a clade of predaceous opossums which can move bipedally by macropod-like saltatorial pouncing (a trait which developed independently from these Australian marsupials), they are also unusual for their specialization towards carnivorous preferences (similar to the unrelated extinct opossum, Thylophorops). They nest in burrows in the bushland during the day and emerge at night to hunt for small animals or carrion. All of them have acute hearing and light-sensitive eyes which are advantageous for nocturnal hunting. Weighing up to six kilograms in the biggest species, they are one of the largest New World marsupials, and capable of killing and consuming lizards, frogs, small birds, and rodents among other prey. They are agile enough to capture flying insects and even bats or birds out of the air on occasion, grasping using dexterous hands or sharp teeth.

It is their speed and agility which are their primary defences against larger predators (mostly reptiles, but some birds-of-prey) and they will twist to dodge lunges and quickly bound away in strides of over a metre, leaving foes in the dust. If they are close enough, they will leap into the nearest burrow out of reach; all burrows are made with at least two entry and exit holes so it is unlikely they can be cornered inside. They are also capable of climbing and retain a semi-prehensile tail, normally used for manoeuvring while jumping, but can act as an extra limb when on trees. If they actually manage to be captured they will attack viciously with tearing bites and strong kicks, making them quite difficult to handle.

There are four known species of coloroo and these have numerous physical and behavioural differences to exploit differing habitats within the tepui complex and also make them easily distinguishable from one another. These are the tabby coloroo, the cobalt coloroo, the giant coloroo, and Alan’s coloroo, which are separated into two different genera. The tabby (or striped) coloroo is the smallest species, at only about one kilogram, and lives primarily in the brushy scrubland. They are also one of the most gregarious species, sometimes gathering in groups of up to one or two dozen; while it is mostly due to a common food source in a small area, there are unconfirmed reports that they utilize these numbers to take down prey larger than them my mobbing techniques. The cobalt coloroo is so named for the band of silvery fur that runs down its body which appears pale blue in certain lightings. This is an aggressive forest dweller of up to three kilograms, an opportunistic predator, but it can take down animals nearly as large as itself. The giant coloroo is, as the name suggests, the largest coloroo species, and a close relative of the cobalt coloroo; it is a forest hunter of any smaller game it comes across in the undergrowth.. These are a more marsh associated species and shows an affinity for aquatic prey, which it catches by a combination lunge of hands and teeth. Alan’s coloroo is a more alpine species, and is the only species known for truly cooperative hunting; pairs will flush prey out of burrows or nests, with one chasing and the other lying in wait as they flee into the open.

Legion Worm: The equivalent of carrion beetles in the Maple White tepui, these are a highly social and specialized scavenging velvet worm species which move and forage in large groups. The continually moist climate allows them to function even during midday (excluding periods of extended full sun), allowing them to tackle more specialized lifestyles. Their antennae-like facial tentacles are highly attuned to the finest aroma of decaying flesh and the movement of scavenging insects. Their own flesh is quite poisonous and they can secrete blistering chemicals from glands behind their head which make them a plague upon any carcass the flesh-hungry swarm discovers. Not only are they carrion-specialists, they also aggressively consume any other necrophagous invertebrates (and in some cases, small vertebrates) present on the body, including other groups of legion worms, effectively granting them sovereignty by force.

Like a swarm of huge technicolour maggots (comparatively speaking, at two inches in length), even the carcasses of the largest animals on the tepuis are stripped down to the bone and inedible parts such as nail and hairs within two or three days, the worms themselves often doubling in mass in this period. These large meals are important as the unpredictable nature of carrion appearances necessitate periods of fasting between; after a feeding, the worms may go five or six weeks without eating with no ill effects. Like many velvet worms, their social system is complex, but in this species it has been elevated to being the only known eusocial onychophoran species. During intermission periods between feedings, the higher ranking females and their young will go into a semi-dormant state to avoid wasting energy while numerous males and lower-ranking (non-breeding) females of the colony will search for new food sources, using pheromone trails to track back to the colony.

Occasionally, often after a large feeding session, the colony enters the breeding stage where the fertile females will produce a communal nest chamber from a modified slime from their facial glands, which quickly hardens, creating protection for the eggs and rapidly developing young. The young are vulnerable from both predation and parasitic infections and therefore are tended to extensively for several weeks, as adults continuously clean them, as the symbiotic dermal bacteria which produce their natural skin toxins settle into the skin of the young worms.

Mountain Peccary: Agile swine which clamber freely throughout the rugged, montane terrain of the tepui with ease. Particularly long legs, flexible hooves, and spike-like dewclaws that allow them to balance and grip steep slopes, making them rather goat-like in morphology (and confidence regarding precarious positions). These relatively small peccaries (generally weighing between fifteen and eighteen kilograms as adults) have an otherwise similar lifestyle to other species, usually living in squads of between five and twenty adults individuals, and being omnivorous but focusing mostly on low-growing vegetation. Using their numbers and fierce demeanour, they may occasionally bully larger predators from their kills to feed on carrion to supplement their diet.

As an adaptation to the limited resources of the isolated environment, they have relatively small litter sizes, averaging only two piglets and breeding only every other year. Both sexes possess large tusks which make formidable weapons against predators. Behaviourally, the species is much more sociable towards one another than most other swine despite smaller herds; in order to ensure continuous food supplies in the enclosed ecosystem, they are nomadic and do not hold territories, but will leave behind scent markings regardless to communicate with other herds that may pass through the area after them so that groups can avoid one another whenever possible and not have to compete for food.

Instead of physical combat, males possess bony flanges along the sides of their faces similar in structure of the distantly related warthogs which become with colour during breeding season, and rivals will engage in a ritualistic “dance” with their heads bowed to determine the superior individual, producing rapid clacking sounds with their tusks to intimidate opponents. Only extremely rarely will this fail and a scuffle ensue. Outside of breeding, males are otherwise peaceful towards one another, and all members of the herd participate in protection of young, regardless of relation. As expected of pigs, they are quite intelligent and follow the flowering seasons of differing plants in their circular journeys.

Glowhoppers: A tribe of treehoppers known exclusively from the tepui system, likely having radiated from a single species which arrived in the isolated environment several million years prior. All possess of spectacularly ornate projections of the carapace which act as both display structures and anti-predator defence (both sexes possess these, but they are much more exaggerated in males). All species have very prominent head and thorax projections which are quite large, rendering them completely flightless. However, such structures are not unknown among the plant-hoppers, and what truly marks members of this clade as unique is a method of communication which is very rare among terrestrial animals, they utilize bioluminescence to attract mates. As the numerous species all inhabit the same ecosystem, different species use different hues of glow and have differing patterns of flashes to avoid confusion amongst one another.

During certain periods of the year, the Maple White Land bushland and forests light up with the pulsating glow of tens of thousands of glowhoppers of several different colours. Although flightless, they still retain powerful back legs that allow them to bound great leaps. Although very large, the ornate exoskeletal projections are hollow and lightweight and start out soft when they metamorphose from nymphs, quickly lengthening and stiffening over the course of hours. Hordes of the herbivorous insects can cover great distances as they scour areas of preferred vegetation through their sap-sucking proboscises. The jagged projections and chemical luminescence render them bad-tasting to most predators as adults, although juveniles are more plain, lacking any real defences aside from the hopping abilities and suffer heavy mortality.

There are three known species of glowhoppers representing two different genera, the antlered glowhopper, the crown-of-thorns glowhopper, and the three-horned glowhopper, and all three reach a similar size of about an inch in body length (although often appearing larger due to extensions of their carapace). The antlered glowhopper is a predominantly rocky dwelling species due to the extremely broad and spiny projects of its thorax which make it cumbersome in more confined areas and can be found in great number in certain low-growing shrubs, but disguised by their unusual shape and speckled green colours. The crown-of-thorns glowhopper species is a more generalist species generally found in the more open prairies and brush. The three-horned glow hopper is the most arboreal species which is able to disguise itself among the flowering plants, although it can also secrete a toxic fluid from abdominal glands which it accumulates from its diet.

False Pangolin: A smaller close relative of the knifeback porcupine, the two likely descended from a single species that become isolated in the montane habitat several million years prior, diverging into extremely different forms. Much smaller and more specialized than the knifeback, it has lost use of most dentition except for its elongated incisors and the other are primarily vestigial, and the muscular tail is reduced to a short stump which is covered in large, thick spines which protrude for protection. The scaly armour does not protrude and instead lie in a flattened, overlapping coat three layers thick.

A primarily tree-dwelling species, using hooked claws to confidently climb trees in search of the worms and insect larvae it prefers to feed on. This is a primarily worm-eating species; the molars are highly reduced as it consumes mostly soft invertebrate prey (with small fruit and the occasional egg as supplements), which they can pry out of the wood with powerful bark-tearing claws and tweezer-like incisors in an elongated snout. Sensitive whiskers and and even more finely attuned hearing are the tools used for detecting the movement of earthworms beneath dirt, the clipping of leaves by hungry caterpillars, or the gnawing of grubs inside tree trunks.

It’s not uncommon for them to accidentally drop out of trees trying to walk on branches too thin to hold their weight, but their stocky build and scaly armour protects them from the impact, and they easily walk off most such plunges within seconds. However, the weight of the eleven kilogram animal striking the cranium of a human explorer from twenty or thirty feet up is a credible threat with the Maple White Lands. Using sticks and branches, they create small semi-permanent nests in trees which function primarily as sleeping chambers. They are built with only one entrance, making it impossible to sneak up on them while they are inside and alternate nests every few days to prevent ambush predators from growing wise to their home.

Doctor Crab: A species of small, mountain-dwelling, South American land crab which has a very unique lifestyle. Small communities of crabs live alongside the banks of streams and bodies of water, creating communal pits by clearing out vegetation and collecting loose debris. These render their living spaces quite conspicuous, and deliberately so, as these are cleaner crustaceans which are advertising their cleaning stations. These are recognized by all inhabitants of the Maple White mountains and animals of all kinds will regularly visit these stations to be picked clean of parasites, skin flakes, and general detritus. The crabs are extremely quick and will be on their patients in seconds (having likely evolved from a more opportunistic ancestor which would have needed to flee quickly at a moment’s notice), throughly checking over them for any delicious abnormalities.

The hooked feet allow them to easily hook onto the hair, feathers, or scaly skin of any patient, and finely serrated, tweezer-like pincers are adept at clipping off edible parasites or similar nibbles that are fed into the mouth. Working very quickly, three or four crabs can thoroughly clean their host from top to bottom within an hour despite only being about three or four centimetres in carapace width, allowing them to sweep through numerous hosts in a single day. There is certainly no shortage of animals wanting to be cleaned, although the crabs are not the only creatures within the tepuis which have adapted to a life of symbiont cleaning and often other small cleaners, such as certain bird species, may take up spots near doctor crab clearings. The species is not a completely obligate symbiont and if necessary, can feed itself by catching small insects or grazing algae.

The doctor crab is a fully terrestrial species and deposits relatively small clusters of eggs in small isolated pools where they are tended to by the parent crab, and undergo metamorphosis within the egg, hatching as miniature adult-like crabs. The young crabs are more generalist, and live around the adult cleaning stations, living off of scraps until they grow independent enough to form their own cleaning stations.

Mothbats: Just as the possums of Oceania developed numerous species capable of swooping through the treetops on broad membranes of skin, so too did a branch of their American marsupials develop a similar gliding form. The mothbats are a unique branch of the microbiotherians, all of which are highly effective gliders. Representing three different species of two genera unique to the lost world, these range in size from a hamster to small muskrat in size, but all possess wide, membranous wings which are lengthened by an extended pinkie finger to increase surface area. They are superb gliders capable of carrying themselves over a hundred metres at once with a good launch. During the early morning and late evening, the rocky outcroppings and foliage-covered cliffs of the tepui complex may be filled with the bat-like wings of the rodent-like marsupials flitting to and fro in great numbers. Able to carry themselves huge distances with minimal effort is an extraordinarily useful skull as a small generalist, allowing large foraging ranges. Their large, forward-facing eyes give them exceptional spatial awareness and can function well in very dim light conditions.

The two species of the small-eared mothbats are largely similar in morphology and behaviour, but are separated by habitat preference and ecological niche. The white mothbat (sometimes known as the red-headed mothbat) nests primarily in the more rocky cliff regions, and the bulk of their population resides in the eastern portion of the tepui complex, while the yellow-headed mothbat nest in trees, and most of them live in the western region, although their populations are more scattered. The white mothbat is the smallest species, at only about twenty-five centimetres in wingspan, while the yellow-headed mothbat can reach around forty centimetres across. The big-eared mothbat is much larger than the other two species, with a wingspan of over three feet, and, as the name implies, has much larger ears for exceptional hearing. This is a much more carnivorous species than the two other generalist mothbats, and weighing up to a kilogram, can regularly kill and eat songbirds, bats, and small rodents and lizards. Hunting at night or in the dim hours when the sun touches the horizon, it usually catches animals in their sleep, a fringe of fine hairs along its gliding membrane silencing its movement as it sweeps through the canopy by flight.

Rock Tinamou: One of several ground bird species which have settled within the isolation of the tepui complex, these are one of the most common avian grazers, sometimes congregating in flocks of nearly a hundred. At over four kilograms, these turkey-sized birds are much larger than most other tinamou species, an example of insular gigantism, but have not completely given up flight. When startled, they may flap their small wings rapidly to lift themselves a short distance in the air for a few seconds, but this is the limit of their airborne capabilities. What this more importantly does is reveal the brightly coloured under-feathers of the wings, which combined with the sudden rapid movement, will attempt to startle any would-be predator for just a moment, giving the bird valuable seconds to flee (despite their plump forms, they can move with surprising speed and agility if necessary). Their very limited flight capabilities are also sufficient for wing-assisted incline running up the jagged and uneven slopes it often encounters.

Like many tinamou species, they have primarily mottled, cryptic body plumage which provides excellent camouflage. When motionless on the ground, they resemble nothing more than piles of moss-covered rocks, and the chicks merely small piles of gravel. A sleeping flock of the tinamous out in the open can be easily missed by those not looking for them. While foraging, they often accompany larger herbivores for additional protection (and may feed on the insects and small ectoparasites attracted to them), but are themselves fiercely territorial. Females of one flock will aggressively defend their territories from females of other flocks which attempt to intrude, males (as is generally the case among palaeognaths) are smaller and more passive.

When disturbed, they can unleash a pungent chemical spray from glands near their cloaca; their camouflaging skills are most effective against avian carnivores like birds-of-prey, but is less so with scent-based predators like mammals. So this takes great advantage of their strength, and notably it will not bother spraying this substance when set upon by a bird predator because it is generally ineffective against them, and simply flee immediately if spotted by them. Other grazers find the tinamou a welcome companion, not just for their parasite picking services but, as birds, they have excellent vision and make for valuable extra eyes against predators.

Leech Eel: One of the most physiologically bizarre caecilians known, this is a minute nocturnal hunter of vertebrates, but of the ectoparasitic variety. As its name suggests, it searches for the scent of a sleeping animal and crawls over the length of the body to find the spots where the skin is thinest before it latches on with mucous frill of skin running down its body that forms a seal, and the thin, blade-like front teeth slice through the skin into the blood vessels. Sharing a common ancestor with the Hooded Eel, it has also refined the inherent venom-like saliva, but into a blood thinning anesthesia so that its victim has little clue that it is being fed upon.

The caecilians can double in weight after a good feeding, which generally last for a few hours, so that the victim will wake up none the wiser long after the amphibian parasites have dropped off and slithered away. The caecilians will usually drop off instinctively if the host starts moving, but will inversely tighten their grip if they feel sudden pressure on them (as is the case when parasite-eating animals discover them and try and pull them off). During the day, they remain dormant in temporary burrows in moist earth or underneath fallen logs to conserve energy, becoming active during drops in temperature and/or light level which signify nightfall.

As dermophiids, they are viviparous and eject relatively large and well-developed larvae will immediately drop off and are capable of feeding themselves outright, although generally subsist on the stores of energy gained from feeding on secretions within the oviduct for several days after birth. Full-grown individuals reach only about five to seven centimetres in length, making them the shortest known caecilians, although they can attain a heavier mass than some other minute species, especially after a feeding.

Prairies Dog: A small, plump species of endemic canid, one of the numerous of the unique radiation of the group to South America, more specifically a sister taxon to the more widespread bush dog, which it closely resembles as well. Unlike the bush dog however, the prairies dog is predominantly herbivorous, feeding primarily on soft grasses, new sprouts, tubers, flowers, and fruits, but also capable of grazing on tougher vegetation with its proportionately more robust molars and strong jaw muscles. Meat and related food items make up only a small portion of their natural diet, and when it does, it consists mostly of insects and eggs of reptiles or ground-dwelling birds than vertebrate flesh (expectedly, canines are small).

Similar to bush dogs, these are a very squat, short-legged canine adapted to foraging near the ground, and they reach a similar mass. They utilize natural forming crevices or abandoned burrows created by other digging animals as their dens and form monogamous pairs which stake out territories in scrubland and forest. They are highly social and remain close throughout their life; pairs will watch each others backs while foraging, scent mark territorial boundaries simultaneously, and work together closely in care of pups. The diet of the young pups which have yet to leave the den is higher in animal-based foods than adults, but soon after leaving the den they begin to gradually incorporate more vegetation into their diet. Even after gaining independence, offspring of the dominant pair often remain alongside their parents for long periods, assisting in caring for their later siblings, or may leave for long periods and return to their parents on a whim.

Because of their short bodies, they utilize a wide range of loud calls to maintain communication between individuals. Unusually, when threatened, they’ll utter loud hisses to mimic the calls of the large reptilian predators they coexist with to momentarily startle predators, at which point they will attempt to retreat to the nearest burrow. Although rarely weighing over seven kilograms, they are incredibly ferocious when cornered, attacking with savage bites no matter the size of the foe, and their hisses secondarily act as distress calls, often alerting nearby prairies dogs which will rush to the defence of family members.

---

My compilation of animal entries for 's latest spec challenge based on The Lost World. Featuring cameos by 's Gwangi , and 's Crab-Eating Legfish . Colouring of the False Pangolin and the Glowhoppers was assisted by , and the Leech Eel was also DD66's idea.

Related content

Comments: 29

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

Just like last year, this is definitely one of my favorite entries. Love the realistic take on the setting while still being weird and cool! You continue to be an inspiration for me and my own spec projects

👍: 2 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 3 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0