HOME | DD

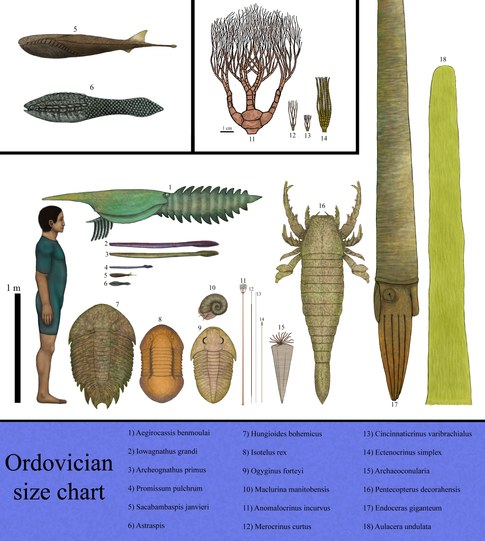

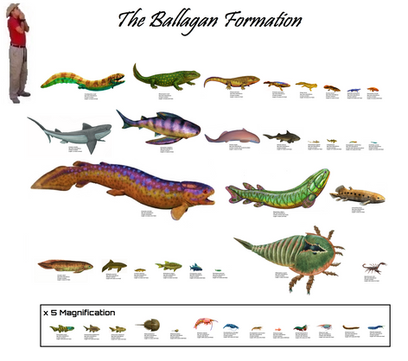

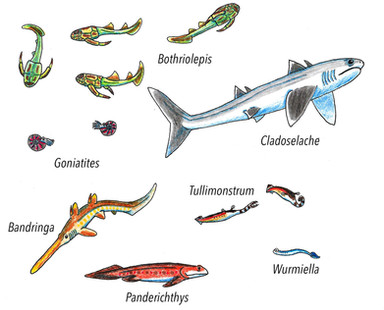

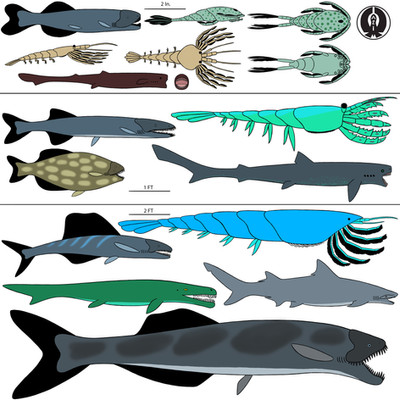

Dragonthunders — History size chart: Devonian

Dragonthunders — History size chart: Devonian

#paleozoic #placoderms #devonian #dunkleosteus #fishes #hyneria

Published: 2020-11-23 23:37:29 +0000 UTC; Views: 88813; Favourites: 625; Downloads: 205

Redirect to original

Description

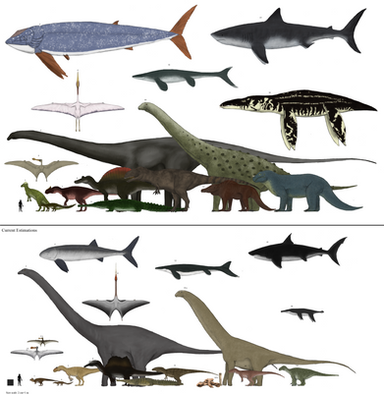

Though the Silurian period most of life had shown increasing development and complexity that created a new ecological and trophic landscape with new types of fauna and flora, new anatomies and new environments, formed by pioneering species that crawled through the sand and mud of the bottoms and beaches, both in the sea and on land, and it is during Devonian that this impulse reaches its zenith. This period started some 418 million years ago and finished around 358 million years ago, lasting around 60 million years, it was a very dynamic period of changes in many geological, ecological and biological aspects; two of the three major continental masses separated from Gondwana, Laurentia and Baltica, collided together forming a major continent on the south tropics called Euramerica, this would be coming more close to Gondwana, in course to form Pangaea; the land flora have been established formally and evolved eventually from small liverworts and moss like plants to more complex forms including the first trees, and thanks warm climate though during this period swamp and forest spread though many coasts with different kind of plants that evolved though most of this period, covering on green the continents for the first time in earth’s history.

On terms of fauna, diverse groups of jawed cartilaginous and armored fishes became cosmopolitan and widespread, alongside them lobbed finned fishes with the eventual appearance of the first tetrapods ancestors, the evolution of the first sharks and ray finned fishes, vertebrates expanding and conquering marine and freshwater environments, and although jawless fishes were still diverse during the early part of this period, they would eventually decline probably for the competence of the former group; arthropods were thriving on water and specially on land becoming a major colonizing clade with arachnids, Myriapods and the first hexapods appearing; eurypterids were still abundant and trilobites had its last biodiversity glory; cephalopods were expanding in different forms from shelled as well shell-less and the first ammonites evolved, and major reefs formed by brachiopods, crinoids and different kinds of sponges thrived.

Although with this impressive development, the end of the period would be marked by the second mass extinction event on earth history which would wipe out these outstanding clades. This event, or better say these “events” have been hypothesized were triggered by separated calamities (volcanism, asteroids and anoxia events) that affected greatly aquatic environments which exterminated a great amount of marine fauna, including most of the successful armored fishes, and reduced greatly others cosmopolitan groups like trilobites, crinoids, nautiloids and eurypterids, but at the end this would burst a subsequent evolutionary radiation of many of the surviving groups. Although the demise of the Devonian was as devastating as the Ordovician extinction, though this period a good amount of peculiar titans evolved, including the first megafaunistic vertebrates on earth’s history as well the first tall forests.

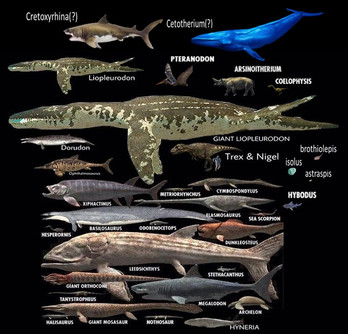

Vertebrates as it was mentioned before, had its major peak in diversity on this point in different ranges of forms and size, conquering major roles in the trophic chain and becoming some of the dominant groups of animals; this was reflected since the end of the Silurian with the evolution of different types of fishes, including the first Gnathostomes which flourished greatly in the Devonian thanks to their jaw development that brought them the tools to obtain a good amount of new niches becoming top chain predators, using their specialized jaws to pierce, crush, slash and butcher, many grew up exponentially from those small species less than a 1 m long to true titans becoming the first megafauna vertebrates on earth history. The major samples of it were the Placoderms, the most prominent clade of gnathostomes as well the most characteristic group of jawed fish of the Devonian. Many species were heavily armored around the head and trunk, being the rest of the body pretty much armor-less covered in small scales or almost devoid of these, most if not all were carnivores, occupying different positions of the trophic chain in every aquatic environment.

Arthrodira were among the most successful of the placoderms in terms of niche and morphological adaptations thanks to their efficient jaws which due to the way their joints were structured, these allowed them to do varied degree of movements including the ability to move both parts of the jaw giving them a more larger mouth opening; as many other groups of placoderms they lacked teeth (Except for a particular exception) and instead they had a sharpened bony plates edges, some well-shaped for slice and crush in every bite. Apart of some variations, the basic arthroridan had an oval or round heads with their eyes located on the front, this head is separated from the trunk shield and in advanced species the chest is partially reduced; based from complete individuals like Coccosteus is known that they had a more or less complete arrangement of fins similar to other jawed vertebrates with pectoral, pelvic, anal, and two dorsal fins.

An incertae sedis species named Carolowilhelmina geognostica is known from a partially fragmented upper skull which is about 40 cm long, with a peculiar elongated snout, is depicted as a swordfish like animal probably adapted to a pelagic lifestyle, based from the size of the fragment the animal could have been around 2 to 2.4 m in length.

Actinolepidoidei were a clade of benthonic arthroridan which were characterized by their flattened circular/triangular bodies which some groups possessed peculiar elongated shield armor flaps, and noticeable reduced vision probably for being high adapted to live in the muddy bottoms, many species were about a decimeter in length being one of the largest genus Phyllolepis reaching around 40 centimeters to almost a meter in length.

Phlyctaenioidei were other benthonic dwelling clades, although instead of having a very flattened bodies they were more robust in their trunk armor, some with very large lateral flaps and humped pyramid shaped dorsal plates and very reduced heads almost similar to Antiarchs although with a basic arthrodire jaw, one of the most known genus also has one of the biggest size being Groenlandaspis riniensis with a fragment scaled would have formed a body shield length of 45 cm, making it around 1.1 meters in length.

Brachythoraci were the major and most diverse of the arthroridans, they originally diversified as benthonic dwellers just like the other two groups in the early Devonian, but eventually during the middle and late Devonian they would expand into pelagic forms and diversifying in different niches, some becoming the first large animals though the period such as the still inc. sedis Confractamnis johnjelli reaching up its 2 meters in length, and during the end of the Devonian would become the dominant megafauna clade, some of the predominant features in this group is the gradual reduction of the trunk shield over time as well the development of the jaw structure

There were the Basal forms:

-Holonematidae were a robust clade of Basal Brachythoraci, with peculiar barren shaped trunk shields and small heads with a evident strong bite, able to feed in hard material like stromatolites algae, this group is mostly known by the genus Holonema which contains the most complete remains, meanwhile the rest is formed by fragmentary specimens of even bigger size, many from the barren trunk shields which some species show a peculiar flattened crest growing up the trunk, from these some species like Belemnacanthus giganteus which is known from a fragment of the upper part had a shield size of 50 cm and based from Holonema it could have been around 1.5 meters in length.

-Buchanosteida were semi-flattened placoderms with elongated bodies and heads, and unlike those others almost blind bottom dwelling species these possessed large eyes, species like Exutaspis megista had a possible length of 1.3 meters and the more wide Burrinjucosteus asymmetricus a size of 1.5 meters and a width of 30 cm.

-Homosteidae were other of the semi-flattened groups of placoderms but unlike the others these were one of the major groups of these basal species that have reached considerable sizes during the early Devonian, becoming into the largest animals of that moment, such as Tityosteus rieversae with 2 to 2.5 meters long based from some trunk shield preserved, and the more fragmentary Antineosteus rufus calculated to have been around 2.5 to 3 meters in length.

Then there were Eubrachythoraci were more or less formed by small active swimmer species, many bottom dwelling, including some of the most complete in specimens such as the freshwater Coccosteus which was around 20 to 40 cm in length, although other species grew up even larger like Livosteus which based from the fragment of a shield armor it was probably around 2 meters in length.

And finally the Pachyosteomorphi which include some of the most pelagic as well major megafauna’ placoderms species that dominated during the middle and late Devonian, although there were some families with small sized which their largest individuals reached around a meter, species like Gymnotrachelus hydei of about 1 meter and Draconichthys elegans 1.2 meters.

Titanichthys became one of the first large filter feeding vertebrate to evolve on earth, with species such as T. clarkii with head-trunk armor length of 1.8 meters and T. termieri with a head-trunk armor length of 2 m, in total they could have been able to reach 5 to 6 meters scaling from more complete relatives; Dinichthys herzeri (A genus very widespread for being used to call most famous large arthrodire specimens including Dunkleosteus) able to reach its 5 m in length, or the even larger but still light shaped Gorgonichthys clarki with a size around 6 m. Heterosteus ingens is an interesting sample of flattened form for being adapted as a bottom dwelling animal compared to other Pachyosteomorphi almost convergent to Homosteids but with their shield head armor more trapezoid shaped, which had an armor length and width of 1 m and a possible total length of 3 m long; And above them, the genus Dunkleosteus dominated though their environment as the apex predator of the late Devonian sea, with 10 species is known that D. terrelli had a variable size which some of the maximum size around 6.9 to 8.79 m in length, making it one of the biggest animals to exist at that point.

Antiarchi were the second most successful group of placoderms, they were mostly bottom dwellers of freshwater environments, characterized by their robust shield trunks, in many species the pectoral fins were covered in bone almost arthropod-looking; their heads were pretty much short in comparison to the trunk, with their eyes positioned very above and their mouth located ventrally; Their posterior was totally armor-less, with just a dorsal fin and a fluke, lacking any other kind of fins. Although they weren’t as gigantic as their Arthroridan cousins they still attained some outstanding sizes, some species such as Asterolepis scabra reached 1.2 m in length and the genus Bothriolepis (one of the most cosmopolitan with 100 species recognized), specifically B. rex is calculated to be 1.8 m in length but based from the cranial material found.

Ptyctodontida were other of the peculiar non-arthrodire placoderms that were characterized by the lack of a prominent armor plate being their head and a narrow part of the front region formed by reduced bony plates. They share some resemblance to living chimaeras for having large eyes, small short mouths big heads and large bodies. They were mostly bottom feeders adapted to devour armored invertebrates they could find. There are very scare in remains with some small species found with complete individuals including Campbellodus and Materpiscis, although based from large isolated dorsal spines from the genus Eczematolepis which reached some 25 to 30 cm in length, these could have grown to 1.5 meters.

Petalichthyida is other group with characteristic flattened body armors, large and exaggerated lateral spines shields, and elongated whip like tails, the most common species known of these is Lunaspis which is found in many regions of the world with complete specimens, although most species are small in size reaching some decimeters in length, the species Macropetalichthys rapheidolabis had a skull size of about 23 cm in length, which comparing with complete relatives it could have been more or less around a meter in length.

Rhenanida is a clade which unlike others they had a high flattened body, mostly composed by the pectoral fins being something convergent to rays, skates and angel sharks, with a high reduced head and trunk shield only occupying a minor part of the front body, the rest of the body was armor-less covered by a series of scales and small plates, and for this made their bodies difficult to fossilize, so most species are high fragmentary. Gemuendina stuertzi is known by complete individuals raging around 30 cm in length, and from some descriptions it was able to reach lengths of 1 meter, making it one of the largest species of this clade.

Acanthothoraci represents a group of only early Devonian placoderms that resemble Chimeras and Ptyctodontida in shape but unlike those they were heavily armored with a large head and body shield with unique plate patterns and rugose or grooved surface as well prominent curved spines. Many species are fragmentary with often somewhat complete body pieces and skulls, based from scaling specimens some of the biggest species belongs to the genus Murrindalaspis, which was around 1 meter in length.

Osteichthyes were alongside the first placoderms since the late Silurian but in a different evolutionary trend having a successful occupation in key niches though saltwater and freshwater environments in a minor scale, and unlike placoderms and many others fishes they were free of a body armor with a ossified skeleton; maybe one of the important anatomical developments was the evolution of lungs, which allowed them to gather oxygen from the air and absorb it better that they could on water as well keep buoyancy on water; in some species the first advantage would be a great useful part for the next step on colonizing new grounds.

Starting with the most prominent and probably the most relevant of the groups of the time, Sarcopterygii were among some of the thriving groups under the seas and freshwater as since the start of the Devonian, they were very varied in body shape and size with different behaviors similar to bony fishes in most cases being carnivorous species, some of minimal size, and other obtained major lengths allowed them to become the apex predators in freshwater environments.

Onychodontiforms are among the earliest groups of lobed finned fishes as they were around as far as the Late Silurian, existing though the whole Devonian until they became extinct at the end of the period, one of the major features than distinguish them from the rest of Sarcopterygii is their dagger-like tooth whorls that grew up from the front lower jaw as well their flexible articulations on their heads allowing them a great degree of jaw movements. From all of these, Onychodus prevail among the biggest representative of this group as well the largest Sarcopterygii that inhabited saltwater; it was a large ambush predator that preyed on hard shelled fishes like Ostracoderms and Placoderms. Most complete specimens belongs to small individuals of around 40 cm in length, but based from comparison of large fragmentary jaw remains is speculated they could grow around 3 meters, even possible 4 meters in length.

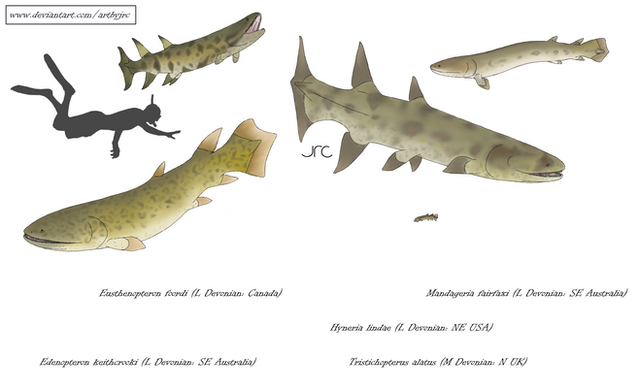

Tetrapodomorphs were unique compared to other of the Sarcopterygii from the period, they developed forefins modifications including humerus with convex head articulated to the socket of the shoulder joint, as well the presence of a choana. The group is formed not only by all living tetrapods but also some “intermediate” sister taxa that existed though the Devonian, many still preserving the basic Sarcopterygii shape. All of the Devonian species were carnivorous, mostly inhabitants of freshwater environments, some were at the top of the trophic chain like the Tristichopterids (being one of the most famous member is Eusthenopteron) including species like Eusthenodon wängsjöi with a size of about 2.3 meters in length, and one of the biggest bony fishes of the Devonian, Hyneria lindae, which based from isolated remains including teeth has been calculated to been around 3 m in length.

Then there were the Stegocephalians, more derived that previous groups this would give rise eventually to true tetrapods in the next millions of years, this clade mostly include all the last relatives of true tetrapods that existed on the Devonian, all characterized by the development of advance forelimbs which is noticeable their evolution across the Late Devonian with increasing modifications from the basic fins to developed articulated limbs with hands and multiple fingers which would allow them to crawl onto land becoming the first land vertebrates on history, many species were small reaching less than a meter in length, some of the largest species included the famous chubby Ichthyostega with a size of 1.5 m in length, the fragmentary long jawed Elginerpeton with a jaw and few bones it has been calculated to have been around 1.7 m in length, and the iconic Tiktaalik roseae which scaling one of the most complete specimens with one of the largest it gives a size of around 2 to 2.7 meters in length.

Dipnomorpha are the closest relatives of Tetrapodomorphs within the Sarcopterygii sharing a same node, although they developed by convergence similar features to these with exception of their derived forelimbs, and unlike living lungfishes they presented a high varied amount of diversity during this period. The clade was formed by the known Dipnoi which unlike the current freshwater mud dwelling species they possessed separated dorsal fins, basic tooth plates, more ossified and articulated skull, etc. One of the longest species was Dipnorhynchus reaching around 1.5 meters in length. Another group were the Porolepiformes, these once were suggested to have been ancestors of salamanders and caecilians apart of tetrapoda, although this has been debunked, they shared similar tetrapodomorph features as well hinged joints on the anterior and posterior portions of the braincase probably facilitated a wider opening and fast closing of the mouth. During the Devonian many species were small less than a meter, although some other reached considerable size like the carnivorous Laccognathus with a length of 2.5 meters.

Actinopterygians or at least their oldest ancestor’s remains would appear in great amount during the middle and late Devonian. Unlike sarcopterygians their fins had a narrow and not fleshy base, triangular caudal fins, large eyes, among others features. Most of these early being these were formed by minuscule species that didn’t grew up more than some decimeters in length, although one species, the barracuda-like Tegeolepis clarki was able to grew to a length of one meter.

Chondrichthyes had a successful evolutionary path during the Devonian, not only few of the existing groups expanded though the new environments but also new clades rise up and claimed some minor parts of the ecology as pretty much medium sized to small predators.

Holocephali did their appearance on this point, they were not like the slow deep water dwelling specie of today, instead they were more varied in body shape, formed by groups similar to sharks in terms of morphology and niche diversity with many active surface or shallow water dwelling species like Cladoselache (which is considered to be close related to Symmoriida, which these last have been reclassified to be within this group) is one of the best known genus of early chondrichthyans due to the well preserved specimens found, most of them species were small around some 30 to 60 cm in length, but others like C. kepleri could reach lengths of 1.6 to 1.8 m in length.

Meanwhile there were variety of Elasmobranchii that were in a similar ecological position with not great external variations with the exception of their dentition, some like Antarctilamna ultima outstanding for its size with some preserved individuals calculated to be around 1 meters and based from isolated teeth scaled would make an animal of about 2.5 meters.

Acanthodians stayed as small fast nektonic swimmers with streamlined bodies, even with the subsequent rise of the placoderms and bony fishes, they kept relatively well with more varied degree of morphologies. Most of these were small on size, but some species would become giant to a scale similar to medium size chondrichthyes around the early Devonian, this is exemplified with the species Xylacanthus grandis, a ischnacanthid only known by a jaw preserved of around 35 cm long, this scaled with complete relative preserving similar proportions shown they could have been able to reach lengths of 2.5 meters.

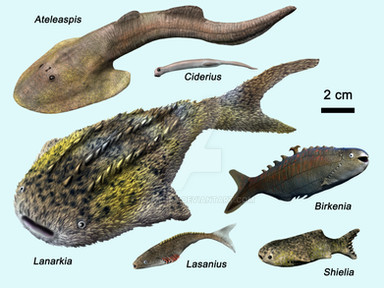

Although Ostracoderms due to the eventual rise of jawed vertebrates and subsequent mass extinctions that happened though the late Devonian were doomed, but they still had a good moment of diversity during the early and middle Devonian as they were still a very widespread group though marine, brackish and freshwater environments, some varied further their body morphologies, evolving into more divergent shapes and developing complex armors arrangements and other features, and at the end some of the biggest forms of this variety would appear.

-Heterostraci kept different body trend that varied depending of the niche and lifestyle they had, from the basic oval shaped forms from the Silurian like Lepidaspis serrata of about 30 cm to the high derived flattened bottom dwellers buried in the seabed like Eglonaspis with a shield size of 30 cm and a total length of 60 cm, and some more hydrodynamic streamlined forms like Pteraspids which seems to have been the most nektonic of all, which the largest of all was Rhinopteraspis dunensis of 40 cm long. But all of them were dwarfed by the Psammosteids, a group of flattened and robust agnathans characterized by their peculiar armor arrangement which unlike most species it was a mix of scaled and large plates distributed with a specific patter across the body, one of the best known species of this group was Drepanaspis which is referred as an early species with a size of around 30 cm, the group kept a growing trending where for the next millions of years the new species started to become more streamline adopting a peculiar hydrodynamic plane shaped body with the pair of lateral plates becoming into large concave wing like projections, with a ventral plate projecting like a keel, and eventually evolving into true giant among its group, the major sample belongs to Tartuosteus maximus with a body size calculated to be around 1.8 m in length, with a body span of 1.4 m, making it one of the biggest agnatha ever.

-Galeaspids were limited to the detritus and soils of the environments, many adopted new shell shapes and became alongside common Heterostraci quite varied in shield morphologies during the early Devonian, they diverged more in body shape developing in different cephalothorax structures, most were minuscule, at least some species such as Eugaleaspis reached its 12 cm in shell length.

-Osteostracans were among the most successful of the Ostracoderms though the Devonian even at the end, they were growing in number of species and developing further their morphological features, among some of these species that appeared would include the famous Cephalaspis with a size of 25 cm, but some species reached large sizes, like Trewinia magnifica with a length of 70 cm and the even bigger Parameteoraspis hoegi that was a titan of the group with a head shield of 30 cm of span and a length of almost 1 m.

Thelodonts dimmed with the shift of diversity during the middle and late Devonian, this until their total extinction on the end of the period, but during that span of time they were still common detritus and suspense feeders, some of the most well preserved individuals shared some remarkable anatomical changes and modifications on the body and fins structure compared to previous species, probably for the increasing competition with advance jawed fishes like other groups, some species like Turinia pagei were able to reach 30 cm in length.

Arthropods were going towards a major wave of diversification during this age either from land as well from water, the subsequent land colonization established pretty well many of the current orders that would dominate and survive on land for the next 400 million years, as well in the ocean with the rise of jawed vertebrates and the subsequent major mass extinction they reorganized their diversity, although than rather dim their number it just brought them new opportunities to improve and adapt.

Trilobites had an increasing improvement of their numbers from the great loss of families of the first earth mass extinction, although they didn’t recover the diversity of the old days of the Cambrian they were still as diverse as they were during the Ordovician, and with that will appear some of the last big species of this clade such as Odontocephalus around 40 cm in length, and the spiky Terataspis grandis with a length of 45 cm with elongated pygidial spines of 15 cm, giving a total size of 60 cm.

Chelicerata thrived as on land as on the ocean with an outstanding diversity, although Eurypterids had a little downgrade on dominance since the start of the Devonian for the increase jawed predatory vertebrates, being many large forms eventually limited on brackish and freshwater dwellers with a change on geographical and environmental distribution, they didn’t suffered greatly but adapted and outcome the new limitations caused by competence and persisted, becoming into the biggest arthropods that ever lived. Pterygotus is a very well know genus that existed since the Silurian and though the Devonian with many species that had variable sizes ranging from some decimeters to P. grandidentatus which was around 1.7 meters in length, there were other specimens hinted to this genus even larger although at the end they were reclassified with different genus, and the titan Jaekelopterus rhenaniae, a species known from a only claw which scaled with complete relatives and individuals it could have been around 2.6 meters in length, being the biggest arthropod that ever existed. On land, Arachnids dominated the marsh and were going towards inland regions, they had varied aquatic and fully terrestrial forms on which scorpions and arachnids were the apex predators in these early ecosystems, although they didn’t reach the gigantic sizes of those of the end of Silurian with some species like Gondwanascorpio emzantsiensis able to reach about 12 cm in length.

Crustaceanomorpha are a clade formed by many extinct as well extant variety of arthropods that aren’t within Arachnomorpha which included all current living and extinct Mandibulata (Myriapods, Pancrustacea including Hexapoda) as well many extinct groups since the cambrian, although is during this time many new groups that would evolve into the current clades alive will evolve, including the first land insects, millipedes, centipedes and many others. There were a bunch of species that are difficult to classify within many of these clades, some like the enigmatic Bennettarthra annwnensis which although it counts with a body preserved due to the state of the remains that makes difficult to assert its total affinity, based from comparable similar, this arthropod could have been around 33 cm in length.

Myriapods appeared during the Silurian being small sized species of few centimeters long, even though they presented a quite amount of derived trails including variable segment and limb morphologies, on the Devonian this trend was still developing in many other different clades becoming quite successful in the early land environments. Many fossils of this ages expose that many of these early Myriapods were small in size, but based from 22 cm wide ichnofossils of the genus Diplichnites gouldi, attributed to be from arthropleurids in origin suggest that larger individuals existed, based from genus like Eoarthropleura (which was around 10 cm in length) if it was similar in proportions and number of segments, the owner of these tracks may have been more than 50 cm in length making them some of the largest terrestrial animals of the period.

Is worth to mention about some of the old day Panarthropods such as Radiodonts had in a way survived though this point of time for the only species identified formally, Schinderhannes bartelsi, is small of around some 15 cm long, it shared some remarkable anatomical modifications from its formed ancestors that thrived during the Cambrian and the Ordovician; Although of what it seems their demise at this point with not more Radiodont traces passing from the early Devonian… at least for the moment…

Mollusks had been going through different diversifications, many of the sea dwelling groups started to conquer brackish and freshwater environments (with exception of cephalopods), adjusted their shell shapes as well radiating further not only in ecologies but also shell shapes, adopting new bizarre forms.

Cephalopods during the Ordovician and Silurian a new evolutionary trend started to appear among some groups of cephalopods and was the increasing coiling of the shells as this shape had a center of mass more balanced and being more maneuverable, the whorl builds in itself and manage to hold the elongated size of the shell in a very compact space. One particular group that evolved this form would become for the next hundreds of millions of years into a successful clade, these were the Ammonites, these evolved in the middle Devonian and at the end they were all around the ocean, many small in shell size diameter of few centimeters, but species reached some considerable size on the decimeters, like Manticoceras sp. with a diameter of 40 cm and Gonioclymenia speciosa with a diameter of 50 cm; Nautiloids were also in that trend of coiled shells, although that most straight shell forms became decreasing in number due to competition of ammonites and Coleoids, but this didn’t stop some groups to grew up to considerable sizes, some of the long species evolved from Actinocerids like Deiroceras hollardi which had a shell size of around 2 to 2.6 meters in length.

Gastropods were thriving during a good part of the early and middle Devonian but had a large loss of groups in the subsequent extinctions, many species had a shell size of few centimeters, but species like Turbonopsis shumardi were able to reach its 10 cm in diameter.

Annelids are often scare in remains though many strata apart of ichnofossils as well very special places were preservation is good, which gave little but still essential information about some aspects of their existence and evolution though most of earth history, something like Websteroprion armstrongi, a large polychaete worm which had mouthpieces of 1.3 cm in length, which altogether would have belong to an animal of around 2 m in length.

Echinoderms kept diversifying from the Silurian burst, although with the loss of cystoids the remaining groups thrived on the prolific reefs, with crinoids being prevailing, some of the biggest species were still the genus Scyphocrinites that lived through the early Devonian with a stem of 3 m in length, many subsequent species with complete stems found had a size of around 1 meter in length.

Cnidarians thrived in different shapes though reefs as colonial forms, but solitary species like horn corals were developing greatly forming towering structures, in many cases individuals highlighted in the landscape reef for the tall continuing growing structures created by the individual polyp, one of the most prominent were from the genus Siphonophrentis like S. elongata they were able to build a towering skeleton of around 75 cm to 1.5 meters high, and S. gigantea, a deep water dwelling horn coral that even though it wasn’t tall as their shallow reef relatives it was still big and robust, with a skeleton size going around 30 cm.

Sponges were still abundant reef builders, specially stromatoporoids which were in the peak of their diversity with different forms and species growing layer over layer forming great structures, many being the foundation of whole ecosystems as they were able to grow up in soft substrates instead of hard ones and host a quite abundant number of animals, a peculiar type of these that grew very large were “laminar Stromatoporoid” able to reach a length of 5 meters, with a height of just 20 cm.

Thanks to the remains of fossil spores found on Ordovician strata we knew that there were already land autotrophs similar to early moss as well small fungi organisms, all living in the substrate soil of the coasts and humid regions of the barren empty continents, but it wasn’t until the Silurian where more complete evidence is found of different and more complex land flora, including the famous Cooksonia with a sporophyte of a height of 5 centimeters tall, becoming a prominent plant on the Silurian and early landscape forming sort of a covering very short sized fields, alongside them there were a very outstanding tall organisms unlike anything that could come up after, Prototaxites, a titanic fungal organism that thrived in the absence of the vascular plants, most body remains of these beings vary in width and height, some of the biggest individuals had a diameter of 1.3 meter and a height of around 8.8 meters, making it one of the biggest organisms on land during the early Devonian. Alongside them the first plants grew under their shadows, forming large coastal prairies formed by a mixture of early species, many of these early plants grew up to 3 m tall.

Eventually advancing though the period, plants started to get complex with their transport tissues, developing more varied tube structures that helped them to transport water and nutrients and with it grew up to large sizes, and around the middle Devonian these developed into the first trees forming the first terrestrial forests around the humid regions of the continents growing as high as 8 meters tall, to end up with even taller species able to reach some 20 to 30 meters in height at the end of the Devonian.

References

-Downs, J. P., Daeschler, E. B., Garcia, V. E., & Shubin, N. H. (2016). A new large-bodied species of Bothriolepis (Antiarchi) from the Upper Devonian of Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, Canada. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 36(6), e1221833.

-Gross, W. (1960). Tityosteus n. gen., ein Riesenarthrodire aus dem rheinischen Unterdevon. Paläontologische Zeitschrift, 34(3-4), 263–274.

-Boyle, J., & Ryan, M. J. (2017). New information on Titanichthys (Placodermi, Arthrodira) from the Cleveland Shale (Upper Devonian) of Ohio, USA. Journal of Paleontology, 91(2), 318-336.

-Ferrón, H. G., Martínez-Pérez, C., & Botella, H. (2017). Ecomorphological inferences in early vertebrates: reconstructing Dunkleosteus terrelli (Arthrodira, Placodermi) caudal fin from palaeoecological data. PeerJ, 5, e4081.

-Schultze, H. P., & Cumbaa, S. L. (2017). A new Early Devonian (Emsian) arthrodire from the Northwest Territories, Canada, and its significance for paleogeographic reconstruction. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 54(5), 461-476.

-VAŠKANINOVÁ, V., & Kraft, P. (2014). The largest Lower Devonian placoderm-Antineosteus rufus sp. nov. froeadm the Barrandian area (Czech Republic). Bulletin of Geosciences, 89(3).

-刘玉海, & 王俊卿. (1981). 滇东中泥盆统的节甲鱼类化石. 古脊椎动物与古人类.

-Young, B., Dunstone, R. L., Senden, T. J., & Young, G. C. (2013). A gigantic sarcopterygian (tetrapodomorph lobe-finned fish) from the Upper Devonian of Gondwana (Eden, New South Wales, Australia). PLoS One, 8(3), e53871.

- Eastman, C. R. (1898). Dentition of Devonian Ptyctodontidae. The American Naturalist, 32(379), 473-488.

-LONG, J. A., & YOUNG, G. Acanthothoracid remains from the Early Devonian of New South Wales, including a complete sclerotic capsule and pelvic.

-Daeschler, E. B., Shubin, N. H., & Jenkins, F. A. (2006). A Devonian tetrapod-like fish and the evolution of the tetrapod body plan. Nature, 440(7085), 757-763.

-Mann, A., Rudkin, D., Evans, D. C., & Laflamme, M. (2017). A large onychodontiform (Osteichthyes: Sarcopterygii) apex predator from the Eifelian-aged Dundee Formation of Ontario, Canada. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 54(3), 233-241.

-Obručeva, O. P. (1962). Pancirnye ryby devona SSSR: (kokkosteidy i dinihtiidy). Izdatelʹstvo Moskovskogo Universiteta.

-Downs, J. P., Daeschler, E. B., Jenkins Jr, F. A., & Shubin, N. H. (2011). A new species of Laccognathus (Sarcopterygii, Porolepiformes) from the Late Devonian of Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, Canada. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 31(5), 981-996.

-Gardiner, B. G. (1963). Certain palaeoniscoid fishes and the evolution of the snout in actinopterygians. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Geology Series, 8, 2-pls.

-Ørvig, T. (1967). Some new acanthodian material from the Lower Devonian of Europe. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 47(311), 131-153.

-Carr, R. K., & Hlavin, W. J. (2010). Two new species of Dunkleosteus Lehman, 1956, from the Ohio Shale Formation (USA, Famennian) and the Kettle Point Formation (Canada, Upper Devonian), and a cladistic analysis of the Eubrachythoraci (Placodermi, Arthrodira). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 159(1), 195-222.

-Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences. (1918). Bulletin of the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences (Vol. 12). Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences.

-Gess, R. W., & Coates, M. I. (2015). High-latitude chondrichthyans from the Late Devonian (Famennian) Witpoort Formation of South Africa. Palaeontologische Zeitschrift, 89(2), 147-169.

-Eastman, C. R. (1907).... Devonic Fishes of the New York Formations (Vol. 10). New York State Education Department.

-Ritchie, A. (1975). Groenlandaspis in Antarctica, Australia and Europe. Nature, 254(5501), 569-573.

-Carr, R. K., & Ferbert, M. L. (1994). A redescription of Gymnotrachelus (Placodermi: Arthrodira) from the Cleveland Shale (Famennian) of northern Ohio, USA. Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

-Ruecklin, M. (2011). First selenosteid placoderms from the eastern Anti‐Atlas of Morocco; osteology, phylogeny and palaeogeographical implications. Palaeontology, 54(1), 25-62.

-Tarlo, L. B. (1961). Rhinopteraspis cornubica (McCoy), with notes on the classification and evolution of the pteraspids. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 6(4).

- Gess, R. W. (2011). High Latitude Gondwanan Famennian Biodiversity Patterns: Evidence from the South African Witpoort Formation (Cape Supergroup, Witteberg Group) (Doctoral dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, Faculty of Science).

-Pan, Z., Zhu, M., Zhu, Y. A., & Jia, L. (2015). A new petalichthyid placoderm from the Early Devonian of Yunnan, China. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 14(2), 125-137.

-Obruchev, D., & Mark-Kurik, E. (1968). On the evolution of the psammosteids (Heterostraci). Eesti NSV Teaduste Akadeemia Toimetised, Keemia, Geoloogia, 17, 279-284.

-Blieck, A. L. A. I. N., Goujet, D. A. N. I. E. L., & Janvier, P. H. I. L. I. P. P. E. (1987). The vertebrate stratigraphy of the Lower Devonian (Red Bay Group and Wood Bay Formation) of Spitsbergen. Modern Geology, 11(3), 197-217.

-Nilsson, T. (1941). The Downtonian and Devonian vertebrates of Spitsbergen. VII, Order Antiarchi.

- Andrews, M., Long, J., Ahlberg, P., Barwick, R., & Campbell, K. (2005). The structure of the sarcopterygian Onychodus jandemarrai n. sp. from Gogo, Western Australia: with a functional interpretation of the skeleton. Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of The Royal Society of Edinburgh, 96(3), 197-307.

-Janvier, P., & Newman, M. J. (2004). On Cephalaspis magnifica Traquair, 1893, from the Middle Devonian of Scotland, and the relationships of the last osteostracans. Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of The Royal Society of Edinburgh, 95(3-4), 511-525.

- Klug, C., De Baets, K., Kröger, B., Bell, M. A., Korn, D., & Payne, J. L. (2015). Normal giants? Temporal and latitudinal shifts of Palaeozoic marine invertebrate gigantism and global change. Lethaia, 48(2), 267-288.

- Gess, R. W. (2013). The earliest record of terrestrial animals in Gondwana: a scorpion from the Famennian (Late Devonian) Witpoort Formation of South Africa: Arachnida. African Invertebrates, 54(2), 373-379.

-Bradshaw, M. A. (1981). Paleoenvironmental interpretations and systematics of Devonian trace fossils from the Taylor Group (lower Beacon Supergroup), Antarctica. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics, 24(5-6), 615-652.

- Reimann, I. G. (1942). A new restoration of Terataspis. Bulletin of the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences, 17, 39-51.

- Pohle, A., & Klug, C. (2018). Body size of orthoconic cephalopods from the late Silurian and Devonian of the Anti‐Atlas (Morocco). Lethaia, 51(1), 126-148.

-Oliver, W. A. (1993). The Siphonophrentidae (rugose corals, Devonian) of eastern North America. US Government Printing Office.

-Kershaw, S., & Riding, R. (1980). Stromatoporoid morphotypes of the Middle Devonian Torbay Reef Complex at Long Quarry Point, Devon. Proceedings of the Ussher Society, 5(1), 13-23.

-Hueber, F. M. (2001). Rotted wood–alga–fungus: the history and life of Prototaxites Dawson 1859. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 116(1-2), 123-158.

-Burgess, N. D., & Edwards, D. (1988). A new Palaeozoic plant closely allied to Prototaxites Dawson. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 97(2), 189-203.

Related content

Comments: 38

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 2 ⏩: 1

👍: 1 ⏩: 1

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 2 ⏩: 0

Bro this is incredible! Please continue with the series!!

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 1 ⏩: 1

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 1 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 2 ⏩: 0

👍: 2 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 0