HOME | DD

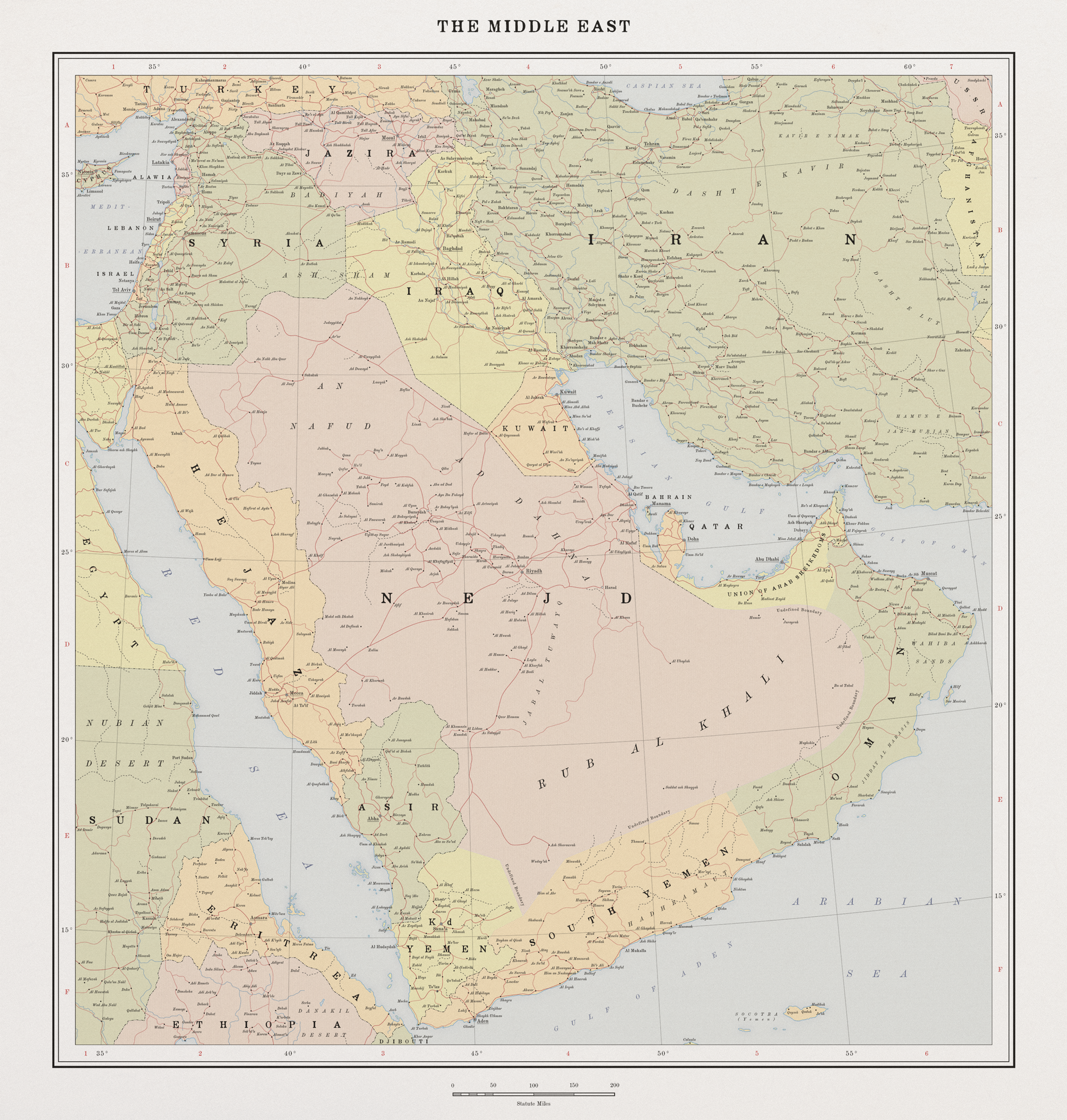

FDrizel — Lines in the Sand - The Middle East in 1974

FDrizel — Lines in the Sand - The Middle East in 1974

#history #iraq #map #syria #vintage #althistory #jazira #althistorymap #alternatehistory #antique #arabia #cartography #historical #middleeast

Published: 2020-12-28 00:00:05 +0000 UTC; Views: 27131; Favourites: 173; Downloads: 53

Redirect to original

Description

The Nicolson-Picot Agreement and the Rise of the Hashemites

Much of Arabia's story in the 20th century can be traced back to the December 1915 Nicolson-Picot agreement, which ended months of deliberation between the British and French during the First World War. The agreement was able to be reached that month after the two parties had finally reached a consensus regarding the extent of the proposed independent Arab state, with François Georges-Picot notifying Sir Arthur Nicolson that he had obtained permission to agree to the towns of Aleppo, Hama, Homs and Damascus being placed under Arab rule. This marked a scaling back of French demands since November, and enabled Nicolson to agree to this proposal in order to secure an independent Arab state in these territories (though at this stage it was not clear that they would belong solely to Syria rather than a larger, unified polity). Lines were drawn on maps that stand today as borders in the modern Middle East, lines which have shaped regional politics and conflicts for decades. Under the agreement, French jurisdiction was placed over greater Lebanon, including a stretch of coastline which Paris designated as an Alawite state, and a large portion of southern Anatolia (though this would be promptly lost in the Turkish War of Independence). The British were equally satisfied, creating a mandate over Palestine and installing two Hashemite rulers in what were essentially protectorates: King Zeid in Upper Mesopotamia (later becoming what we know it as today, Jazira) and King Abdullah in Lower Mesopotamia, or modern Iraq. A third Hashemite brother and one of the most remembered was Faisal, who became the monarch of an independent Kingdom of Syria, made possible by Britain and France's agreement to leave this region unclaimed.

Ibn Saud's Folly

Ibn Saud, Emir of Nejd, had signed the Treaty of Darin in 1915, placing his state under British protection, and yet he retained territorial ambitions in areas nominally under British control. In particular, it had long been a desire of the Emir to annex the Sheikhdom of Kuwait, a desire which came to fruition with the outbreak of the Kuwait-Nejd war in 1919. The conflict mostly consisted of Ikhwan forces carrying out damaging border raids into Kuwaiti territory, creating issues the British appeared willing to solve diplomatically given their alliance with Ibn Saud. The situation shifted in late 1919, however, when a large Ikhwan army succeeded in capturing Al Asimah, the capital governorate of the Sheikhdom. Amidst the chaos that ensued in the town of Kuwait, the British political agent and five British soldiers were killed at the hands of the Ikhwan, attracting ire from London.

Though the group of Ikhwan which had performed this raid had acted outside of orders from Ibn Saud, rather than forcing them to back down, the Emir took the capture as an opportunity to negotiate Kuwait’s annexation. Attempts at diplomacy from Riyadh were only met with fury from London, with the Foreign Office demanding Nejd’s withdrawal, or Britain would dismantle the Treaty of Darin. When no response was received from Ibn Saud, Britain began readying a force to recapture Kuwait from the Ikhwan invaders. The region was to remain under the control Ibn Saud’s troops for months to come as a diplomatic stalemate developed.

In Hejaz, bleak news emerged from Mecca in October 1919, Sharif Hussein had succumbed to the destructive Spanish Flu and had passed away. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Ali bin Hussein, as the King of Hejaz and Sharif of Mecca. In London however, many viewed this turn of events as somewhat relieving. Ali’s father had previously been vehemently opposed to signing the Treaty of Versailles on account of included clauses of providing for a Jewish National home, among other clauses that he viewed as contradictory to the McMahon-Hussein correspondence. Ali, on the other hand, seemed reluctantly willing to accept the treaty, knowing the strain his father’s refusal had been causing in Anglo-Hashemite relations and the promise of increased payments and military assistance in the event of signing the Treaty.

Ali’s decision certainly proved to be fruitful for Hejaz, when Ibn Saud, entering a full year since the tense stalemate had begun in Kuwait, finally decided to move on the long-disputed Al Khurma oasis on the border with Hejaz. However, when a camel charge by the Ikhwan came up against recently resupplied forces of the Hashemite dynasty with new machine gun emplacements, what has been described as a slaughter ensued. After the disastrous charge on the first day of the battle for Al Khurma, the forces of Nejd had already been greatly weakened, and within just another day they were set to rout. Ali had been victorious, and Ibn Saud humiliated.

The costly defeat at Al Khurma was compounded just two weeks later with a bloody battle in Kuwait between British-aligned tribal levies and the Ikhwan, ultimately forcing Nejd out of the region and leaving it in a dire situation. Nejd’s woes were exacerbated with the assassination of Ibn Saud at the hands of disgruntled Ikhwan troops, who had viewed the two humiliations as a failure to materialise key Wahhabi goals. Turki bin Abdulaziz, Ibn Saud’s eldest son, ascended to the throne and quickly aimed to make peace with both the Hashemites and the British so as to attempt to crush what had escalated into a full-scale Ikhwan rebellion against the House of Saud. The 1920 Treaty of Al Qatif defined both Kuwait's boundaries, including the Sheikhdom's claims all the way down to Manifah, as well as the boundaries of the British protectorates of Qatar and the Trucial States with Nejd, curbing further Nejdi expansion in the area. The crisis in Kuwait had rapidly shifted Britain's relations with the House of Saud, no longer viewing it as either a necessary or trustworthy friend in the region after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, and regarding further Nejdi expansion as an inherent threat to the British position in Arabia. Such fears were once again confirmed when the Emirate successfully conquered neighbouring Ha'il in 1923. With concerns that Riyadh was then looking to invade Asir, potentially challenging British shipping in the Red Sea towards Aden, Asir received guarantees from London of protection, securing its independence from an expansionist Emirate it otherwise would have easily succumbed to.

The 1955 Palestine Crisis and the Creation of Israel

Under a British mandate for 37 years by the mid-50s, Palestine had seen tensions build between its growing number of Jewish immigrants and the Arab communities already residing in the territory. At the centre of a worsening political crisis were the British, with Arabs complaining that London was not doing enough to stem the flow of Jewish migration, and Jews arguing that the British authorities unfairly constricted their ability to freely move into and inhabit the lands of the mandate. Already, the mandate had seen an Arab-led revolt from 1941-1943, and violence between Arab and Jewish communities (sometimes occurring as armed clashes and street battles) and acts of terrorism perpetrated by each side were increasing in frequency and severity. In light of this, the British government had resolved in 1954 to withdraw from Palestine by 1957 and to sponsor international talks regarding its future. This was not to be the case however, when a particularly fatal clash between Jewish and Arab mobs in Jaffa killed over 350 individuals, and acted as the catalyst for simultaneous, widespread battles across the mandate. Within a week, the leader of the Jewish Assembly of Representatives claimed that the situation had "deteriorated into a war for the survival of the Jewish community in Palestine", and the Assembly promptly called on Jewish men to take up arms in the conflict. Arab Palestinian communities responded in kind, and from September 1954 to March 1955, Palestine was engulfed in bloodshed.

The 'war' raging in the mandate forced the British to hasten plans for withdrawal, and, with help from the League of Nations, a ceasefire was organised. The London Accords, beginning in April, sought to bring about a permanent resolution to the situation in Palestine after the end of the mandate. The delegates eventually settled on the proposal for dividing the mandate between a Jewish and an Arab zone, and this was formalised in a League of Nations resolution. However, it soon became clear that the implementation of this division would be incredibly challenging, as it was met with fierce resistance, especially among Arab circles in Palestine. It is likely that the proposal would have entirely failed without the intervention of Syrian King Ghazi I, who secretly met with Jewish diplomats and successfully promoted the idea of Syria annexing areas designated for the Arabs under the proposal (essentially areas unconquered by Jewish militias during the fighting) as a means of ensuring a more peaceful transition and providing what Ghazi hoped would be seen as a diplomatic victory back home in Damascus. While the incorporation of swathes of Palestine into Syria did help to calm the tense situation for a time, providing the Jewish Assembly of Representatives the opportunity to officially declare the formation of the State of Israel, Ghazi was seen by many critics in his country to have directly aided in the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine, a notion vehemently opposed by many of his subjects. It would be the public outrage incurred by this act, compounded with a worsening economic situation and the dismissal of a popular anti-Western Prime Minister, that would eventually catalyse the Syrian Revolution of 1957, forever ending Hashemite rule in the country and ushering in a Republic committed to ideals of pan-Arabism and anti-Imperialism. The Syrian Republic would, however, suffer a humiliating military defeat against Israel in 1964 in a war that allowed for the fledgling Jewish state's expansion towards the Sea of Galilee and, more importantly, the capture of Western Jerusalem in the fighting.

The Middle East in 1974

Decolonisation has recently swept through Arabia, with British withdrawals from many protectorates on the Persian Gulf, including most recently the Trucial States last year in 1973. In conjunction with this, the Soviet presence in the Middle East continues to grow, as it maintains close relations with the Syrian government and various other Moscow-aligned organisations operating in the nations of the region. Soviet-backed pan-Arabists successfully expelled the British from Aden in 1971, and the ethnically diverse monarchy of Jazira continues to grapple with a Moscow-funded Kurdish insurgency in its northern regions, making the country deeply unstable in recent years despite help from its Hashemite neighbour Iraq. Similarly, in Iran, an ideologically unusual group of Communist Islamists appear to some observers to be poised to challenge the rule of the unpopular Shah, and international diplomatic efforts have proved unable to end Syrian military occupation of nearly two thirds of Alawite territory. This therefore shows a political trend which some scholars have already dubbed an 'Arab Cold War' in conjunction with the global theatre, as pro-Western and pro-Soviet elements compete to further their influence, though only time will tell whom will emerge on top in a precariously balanced region.

Related content

Comments: 5

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 1 ⏩: 0

👍: 1 ⏩: 1