HOME | DD

maxogame — The Near East in the 1920s

maxogame — The Near East in the 1920s

#alt #arab #britain #east #history #maps #middle #middleeast #neareast #althistory #hashemite #near

Published: 2020-03-21 16:50:21 +0000 UTC; Views: 4897; Favourites: 32; Downloads: 26

Redirect to original

Description

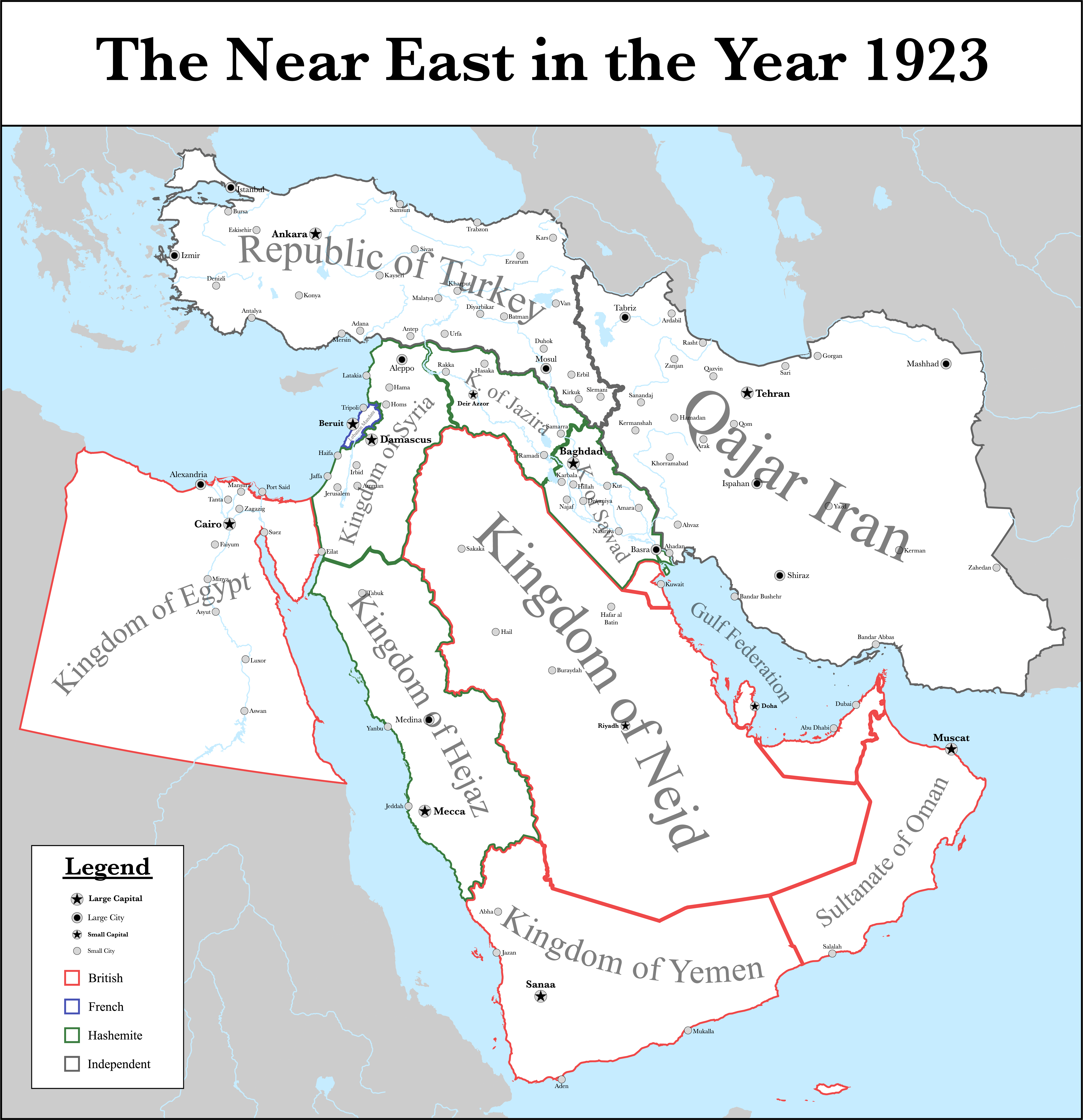

In July of 1915, Henry McMahon, British High Commissioner to Egypt, and the Sharif Hussein of Mecca, began a series of private correspondence in which they discussed a possible revolt of Arabs against the Ottoman Empire and the creation of an Arab state in the post-war era. The boundaries and details of this new Arab state were left purposefully vague, as Britain had other plans for the region. In January of 1916, the British and French diplomats Mark Sykes and Francois Georges-Picot created a secret agreement that would divide the Ottoman territories into spheres of influence for Europe to dominate. This agreement never reached the public, and was eventually buried as to avoid the agitation of the Arabs.Due to the increasing pressure from Zionist groups in the United Kingdom and Eastern Europe, Arthur Balfour, the British Foreign Secretary, sent a letter to the Zionist Federation in 1917 declaring British support for a Jewish state, but the letter did not specify any sort of location. Though some Arabs were outraged, assuming the state would be in Palestine, the lack of specifics did not cause a great stir. Many Zionists in Europe were also unsatisfied, as they longed for the creation of a Jewish state in their homeland.

When the dust had settled and the war was won in 1918, the victorious Allied Powers gathered in Paris to deicide the fate of the world as they knew it. Woodrow Wilson, the American delegate, arrived bringing inspiring new ideas about national self-determination and the consent of the governed. Colonized peoples across the world rejoiced and praised Wilson for his liberalism. However, it became clear to them that Wilson did not pay much heed to the plight of these colonized peoples, and that his ideas were more focused on the people of Eastern Europe and the Near East. Though he did speak out against colonization in general, he did very little to stop Britain and France from annexing Germany’s overseas holdings and continue the oppression of millions across the world.

Instead, Wilson focused his efforts on the peoples living in the former empires of Austria and the Ottomans. Britain and France had no problems liberating the peoples of Europe, such as Czechs, Yugoslavs, Romanians and Poles, but the peoples of the Near East were a different story. Initially the Hashemite family was completely barred from Paris, and only a few Arab delegates were allowed to make their case, largely to counter the Zionist delegation. However, Wilson was skeptical of the British and French, and when he learned of the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement, he decided to take action.

Over the summer of 1919, Wilson hired two commissioners, Henry Churchill King and Charles R. Crane to survey the Levant region and take note of what the people there wanted. On August 28th, they published their findings, and Wilson brought it to Paris the next day as the King-Crane Report. This document would go down in history as the turning point for the Arabs of the Near East. Wilson made such a strong case for the liberation of the Arabs, that Britain and France were forced to abandon their secret negotiations. In September the Hashemite family and many other Arab delegates were officially invited to Paris and formal negotiations began.

But as these men discussed diplomacy, conflicts still raged across Europe. The Russian Civil War had only grown in violence, and their borderlands began breaking away into independent states. The Soviets would eventually recapture their lost territories in Central Asia, Belarus and Ukraine, but the Baltic states and Poland, would remain free. The Caucasus states would see brief independence, during which time they would scramble to control what little territory they could, but were soon reabsorbed into the Soviet Union.

Back in Paris, Britain and France decided that a single, unified Arab state would be too difficult to control and exploit, so instead they offered the Hashemites three different kingdoms in the Near East, each to be ruled by a different son of Hussein. The Sharif himself saw through this attempt to divide the Arab state, but his sons were easily swayed by the idea of having their own states. Britain did what it did best, and played the sons off of each other in order to get them all to agree to this plan. Hussein was powerless to prevent this. Over the next year, the borders of these kingdoms would be drawn up, but there were some complications.

Firstly, the Ottomans were undergoing a revolution in their own right. Bitter over the loss of the war and their territories, the Turks were in a state of unrest and dissatisfaction. Greece had promoted their Megali Idea in Paris and was finally given the green light to annex the land they currently occupied in Anatolia, namely the land around Izmir and the province of Eastern Thrace. Constantinople and the Straits of Bosphorus were under international occupation. Meanwhile, the republic of Armenia had begun invading in the east after Wilson announced his support for an expanded Armenian state carved out of old Ottoman lands. The southern border was still vague, as Kurdish forces controlled the Mosul Vilayet and refused to give in to British occupation.

Finally, in the summer of 1920, Mustafa Kemal Pasha deposed the Ottoman government and seized control of the Turkish military, fighting a three front war against the Armenians in the east, the Kurds in the south and the Greeks in the west. Britain and France, who had already begun pulling out of the Near East following the start of the Hashemite negotiations, chose not to support either side in their cause. The Hashemites, scrambling to control their new nations, signed non-aggression pacts with Turkish diplomats, a deal that was beneficial for Turkey too, who did not want a fourth front. Eventually, in 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne was signed, ending the war and establishing the boundaries between Turkey, Armenia, Greece and the Arab states. A great deal of population movement and genocide took place on all sides during this war, but very disproportionately in favor of the Turks. After this, Kemal proclaimed the First Turkish Republic and began enacting a series of secular, nationalist and Western reforms.

Concurrently to these wars, the Arab states of the Near East were being finalized. Four new kingdoms were established: The Kingdom of Hejaz, ruled by Hussein, the Kingdom of Sawad, ruled by Abdullah, the Kingdom of Jazira, ruled by Zeid, and the Kingdom of Syria ruled Faisal. Hussein’s son Ali was to be the heir for the Kingdom of Hejaz. These four kingdoms would exist in relative harmony with one another, however no official attempt at confederation was made. British influence over all of these kingdoms was definitely apparent, in Sawad much more than the other two however. Abdullah would face intense pressure from the British to allow their oil companies to conduct operations in the region without much interference.

In the Nejd region of central Arabia, a difference conflict was playing out. The Saudi family had been consolidating power and expanding in a series of wars against the competing Rashidi dynasty, which was an ally of the Ottomans. During the Great War, and shortly after the Hussein-MacMahon Correspondence, the Saudis under Ibn Saud signed the Treaty of Darin with Percy Cox of the British government in 1916. The treaty guaranteed the sovereignty of Britain’s protectorates and allies, including the Hashemite family. Additionally, the Saudi family and its holdings would become a protectorate of the British, however this was very loosely defined. By the end of the war, the Saudis had thoroughly defeated the Rashidis, and had consolidated their territory over the Nejd and Qassim regions, even expanding into the coastal regions not under the protection of the British. In the subsequent Treaty of Riyadh in 1921, the boundaries of this new state, named the Kingdom of Nejd, were defined, with expansion into Hashemite and British holdings being restricted. This caused great unrest among the most zealous of Ibn Saudi followers, whom he promptly had executed lest they cause instability in his domain. Meanwhile, the British decided to unite their protectorates in the Persian Gulf into a single federation, disconnecting them from the Indian Raj.

In Yemen, a very similar set of events were unfolding. Following the collapse of Ottoman rule in North Yemen, Imam Yahya Muhammad declared the independence of the region with him as its ruler. However, the mountainous terrain and history of decentralized rule made consolidating power an extremely difficult task. His rule was met with resistance from all sides, leading to him seeking outside assistance in maintaining his power. In the Treaty of Abha in 1922, Yahya met with delegates from Hejaz and Britain to discuss the future of Yemen. In an unexpected turn of events, Yahya agreed to become a British protectorate, under the condition that the Aden Protectorate and the southern Hejaz be ceded to him. Given the historical precedent for Yemeni rule over these regions, both parties were inclined to agree, especially because of the support they would gain from the new kingdom and the stability it would ensure in the region. Once the new Kingdom of Yemen was established, a standing army was creating and supplied by the British in order to consolidate power under Yahya Muhammad. The Colony of Aden was still firmly in British hands.

While most of the Near East remained at least nominally independent, with a few loosely controlled British protectorates on the Arabian peninsula, there was one region in the Mashriq that became an occupied territory: Lebanon. France had felt left out of the many treaties and agreements happening in the Near East, especially considering their interest in the region. Britain had established firm ties with the Hashemites and had cut deals allowing oil companies to drill in their lands. France, on the other hand, had gained very little. So, during the negotiations surrounding the establishment of the Arab states, France demanded a protectorate be created in the “Greater Lebanon” region so that they could protect the Maronite Christian population there with whom they had long-standing ties. Although many of the Arab delegates protested, including Hussein, the King Faisal of Syria agreed, believing this may be a necessary concession in order to continue the already tense negotiations. In October of 1920, French troops landed in Beirut and began dismissing all Arab political bodies and institutions. By the end of the year, a fully fledged French protectorate had been established, with a detachment of French soldiers stationed to ensure stability.

Sometime during the negotiations for an Arab state or states, one Chaim Weizmann, a prominent Zionist leader in Europe, met with Faisal to discuss the issue of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Weizmann had almost no leverage, as had failed several years prior in convincing Arthur Balfour to mention Palestine in his Declaration. However, Faisal was sympathetic to his cause, and part of him worried about possible Jewish rebellion in Palestine. In 1921, the Faisal-Weizmann Agreement was made public, which stated Faisal’s support for a semi-autonomous region in Palestine for Jews. This was not the independent state many Zionists had wanted, but it was a close second. Some Arab nationalists were outraged, but ultimately this autonomous region would remain part of Faisal’s Kingdom of Syria, quelling most concerns. Zionist organizations and settlers began immigrating en masse, and the border of this new homeland were carved around the initial land purchases of those early settlers, largely in the northern reaches of Palestine. Arab Muslims still made up a large minority, even in this Jewish homeland, which caused a great deal of tension, but ultimately Faisal’s leadership helped guide the region to stability.

In Egypt, a very different set of events was happening. Ottoman claims to Egypt had been more nominal than de facto since Muhammad Ali, but even this ended in 1914 with the establishment of Britain’s formal protectorate. However, a revolution in 1919 headed by Sa’ad Zaghlul and his newly founded Wafd party changed that. Weeks of protests, demonstrations and riots eventually forced the British to withdraw their troops from Egypt, with the notable except of the Suez Canal Zone, which remained firmly under British control. By 1922, the new Kingdom of Egypt was announced, with Fuad I as its monarch. In 1923, a constitution was written that created a three branch government, with a multiparty system and greater political freedoms. Liberal democracy had been established.