HOME | DD

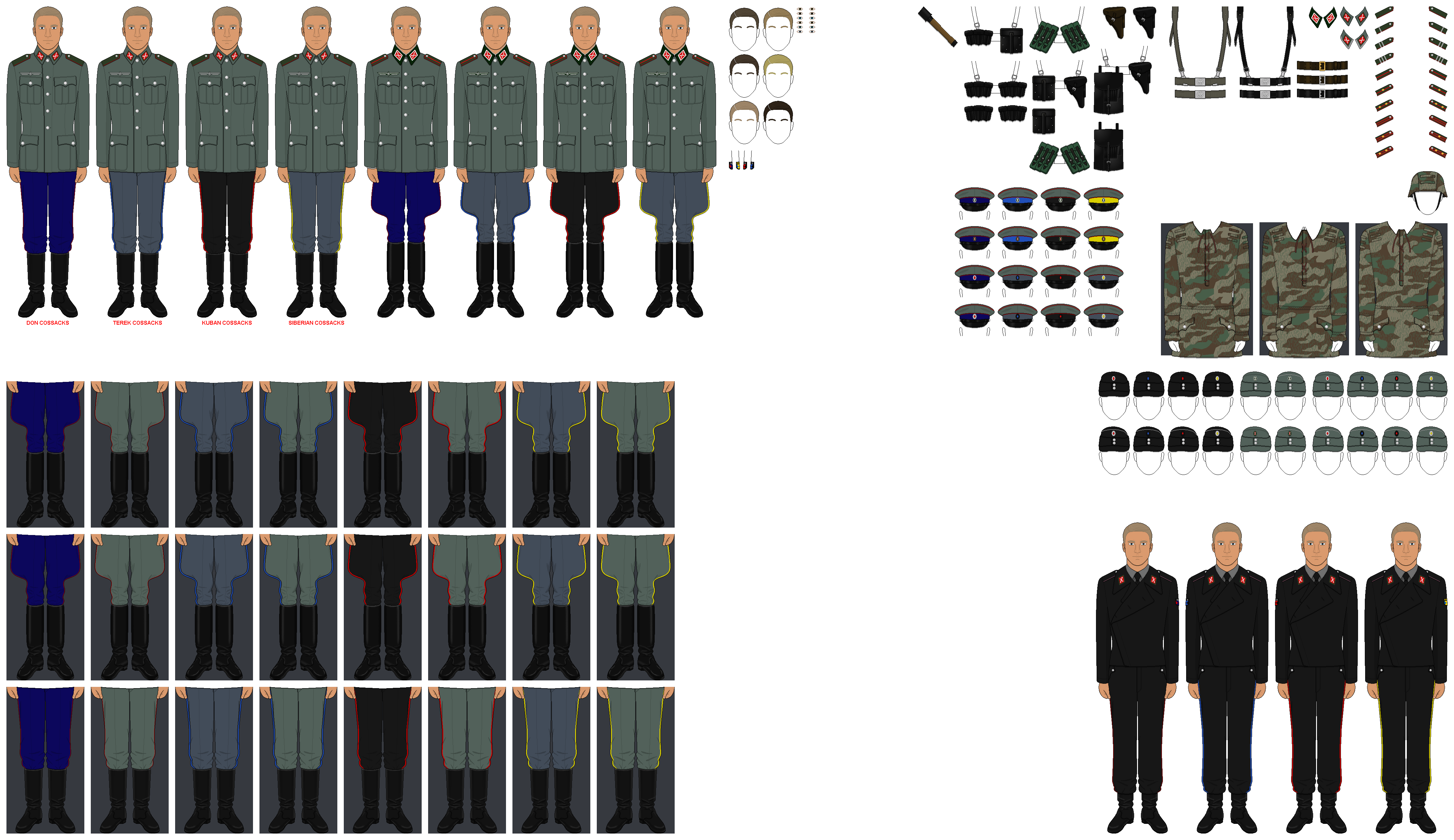

PieJaDak — The Cossacks, Tool (AU)

PieJaDak — The Cossacks, Tool (AU)

#alternatehistory #alternateuniverse #cossack #digitalart #digitalartwork #fanart #fantasy #fantasyart #germany #pixelart #ww2 #germanydeutschland #ww2german #ww2worldwar2 #ww2russian #ww2military

Published: 2021-10-18 20:00:07 +0000 UTC; Views: 18040; Favourites: 52; Downloads: 72

Redirect to original

Description

Backstory:

Of all eastern volunteers, the Cossacks were allowed to muster the largest single concentration. The Cossack, like the cowboy of the American West to whom he bears a certain resemblance, has always enjoyed good press. His image is familiar, his military bearing and romantic costume well-known. He enjoys a reputation for physical hardihood and rugged independence (the Cossacks fought determinedly against Sovietization) which commands respect.

The martial qualities of the Cossacks appealed alike to the Eastern Ministry and the Army High Command. In addition to their known merits, the Cossacks were now revealed as possessing another virtue calculated to endear them to the Nazis. Diligent researchers at Rosenberg’s Eastern Ministry claimed to have discovered that the Cossack is not a Slav, but a Germanic being, a descendant of the Ostrogoths who, of old, had overrun the Ukraine and penetrated as far east as the Crimea. This “remarkable” discovery lent an air of respectability to the recruitment of these warriors. With, or without, the blessing of the Ostministerium, Cossacks had, in fact, been operating as part of the Wehrmacht from virtually the start of the Russian campaign. Sometimes this came about in an almost accidental way. The XL Panzer Corps, for example, acquired its Cossacks in the following fortuitous manner. In the summer of 1942 the corps had captured such a vast host of prisoners that the provision of an escort for them to the rear posed something of a problem. Men could simply released from active duty for a task of this nature. Someone at Corps Headquarters suggested the idea of separating the pro-German Don and Kuban Cossacks from the rest, furnishing them with horses, and allowing them to act as an escort for their compatriots. This was approved, and a Cossack Squadron under a certain Captain Zagorodnyy formed for the purpose. As they departed with their long column of prisoners, no one at Corps Headquarters ever expected to see any of them again. But that September the worthy Captain Zagorodnyy reappeared, saluted smartly and requested his next assignment! Generals are not more willing to turn away volunteers than lawyers are fees, so Zagorodnyy and his men were given four weeks’ training and transformed into 1/82 Cossack Squadron of the German Army.

In the same way other units acquired Cossack auxiliaries. The armoured divisions found them especially as scouts while the security divisions welcomed them as anti-partisan fighters with an invaluable knowledge of the terrain. The summer of 1942 marked the high tide of German success in the East. The Cossack lands (the area around the Crimea and the Sea of Azov, roughly the south-eastern Ukraine), had been cleared of the enemy. In October 1942 the Germans established in the Kuban a semi-autonomous “Cossack District” with a population of some 160,000 persons. A Cossack Nationalist Party (K.N.D) was formed under Vasili Galzkov. It called on its members to “recognise Adolf Hitler as the supreme defender of the Cossack nation.” The Cossacks were allowed to form Sotni (the plural of Sotna – a hundred men: the traditional Cossack military unit). One Sotna was supposed to be attached to each German Security Division in the rear of the front.

The German Army was now in a position to recruit Cossacks from three sources: (i) the “liberated” Cossack areas, (ii) the P.O.W. camps, and (iii) defectors from the Red Army. Of these last, the most significant had been the desertion of an entire Red Army regiment (Infantry Regt. 436), which, with all its officers, went over to the Germans on 22 August 1941. Its commander, Major I.N. Kononov, was a Don Cossack. He was given command of a volunteer unit, Kos. Abt. 102 (later renumbered Kos. Abt. 600), which comprised 77 officers and 1,799 men (although classed as “Cossack” formation, only about 60 percent of its personnel were, in fact, genuine Cossacks). Kononov had a distinguished career in the German service, ending the war as a Major-General.

Two German cavalry officers in Army Group South, Lt. Colonels Jungschulz and Lehmann each formed a Cossack regiment which, in the German fashion, was named after its respective commander. In the Army Group Centre, Lt. Colonel Freiherr von Wolff raised a third Cossack regiment (again this took its leader’s name). Cossack Regiment “Platov” (yet another early Cossack unit within the German army), did not, in this case, derive its title from its commander, instead it was named in honour of count M.I. Platov (or Platoff), a celebrated Cossack officer who harassed Napoleon’s troops during the famous “retreat from Moscow” in 1805. Each of these regiments comprised around 2,000 men with a German cadre of 160 or less. There were also about 650 Cossacks in Reiterverband Boeselager (the Boeselager Mounted Unit), which had been formed as an additional security troop in the rear of Army Group Center.

The Cossacks fought as dragoons rather than cavalry, that is to say, although they rode to battle, they normally fought dismounted. Horse-handlers, often quite young boys, were employed to hold their steeds while the riders fought on foot. In addition to these dragoon Cossacks, there was also a Cossack Plastun (Infantry) Regiment in the German service. This was Lt. Colonel von Renteln’s Kos. Rgt. 6. It was later reconstructed as two separate battalions (number 622 and 623), plus an independent company (No. 638). Later still, it was reconstructed as Grenadier Regiment 630 (it took this number from a former, but now disbanded, German regiment). Von Renteln, born in Estonia, was a former officer in the Czarist Cavalry Guards.

The German officer most closely associated with the Cossacks of the Wehrmacht is Lt. Colonel (later Major General) Helmuth von Pannwitz. Born in Silesia, close to the Russian border, in 1898, the son of a cavalry officer, Pannwitz was a keen horseman. As a 16-year-old cadet, he joined the army at the outbreak of the 1914-18 war, in the course of which he was awarded the Iron Cross 1st and 2nd Class. On active service again in the Second World War, he was awarded “bars” to his previous decorations and in august 1941 was invested with the Knight’s Cross. (He received the Oakleaves a year later.)

Pannwitz struck up a close friendship with Nikolai Kulakov, the Ataman (or Clan Chief) of the Terek Cossacks, who promised the active cooperation of his people in the struggle against Soviet communism. Pannwitz took this up with the Chief of the General Staff, General Zeitzler, and suggested that it might be possible to raise a regiment of Terek Cossacks. Tzeitzler approved and promised that Pannwitz would be placed in command of such a regiment were it to be formed. But when Pannwitz asked where the troops he was to command were, Tzeitzler simply answered, “You’ll have to find them yourself.” The enterprising Pannwitz then toured the front in his Fieseler “Storch” aircraft and, by methods which cannot be described as entirely orthodox, managed to “find” about 1,000 men and six tanks!

The Pannwitz Cavalry Unit (Reiterverband von Pannwitz) proved its worth in battle. In an action in support of Romanian troops, it distinguished itself and Pannwitz was awarded the Romanian Order of Saint Michael the Brave. Convinced of the value of the Cossacks as a fighting force, Pannwitz urged the creation of a Cossack Cavalry Division. The terrible losses in the East made the Army welcome any addition to its overstretched manpower. The raising of such a division was approved, and in April/May 1943 the 1st Cossack Cavalry Division was formed at Kherson (or Cherson) in the Ukraine. It comprised Don, Terek and Kuban Cossacks. The army also sent to Kherson a regiment of Kalmuks! Over 12,000 men were assembled. They were then moved to Mlawa (or, in German spelling, Mielau), north of Warsaw, to what had once been the largest depot of the pre-war Polish cavalry. There was, consequently, ample accommodation for both men and horses as well as a spacious training area. It has to be assumed that by this this time the Germans had discovered the distinction between Cossacks and Kalmuks since the latter did not accompany the others to Mlawa.

More than half of the new division consisted of men recruited directly from the Cossack areas, the rest were volunteers from the prisoner-of-war camps or from among the Ostarbeiter in Germany. The troops at Mlawa included the German-commanded Jungschulz, Lehmann and Wolff regiments as well as Major Kononov’s Kos. Abt. 600. The volunteers were then grouped into two brigades, of three regiments each, as follows:

1st Brigade

1st Don Cossacks Cav. Regt. (Commander: Lt. Col. Graf zu Dohna)

2nd Siberian Cossack Cav. Regt. (Commander: Major Freiherr von Nolcken)

4th Kuban Cossack Cav. Regt. (Commander: Lt. Col. Freiherr von Wolff)

2nd Brigade

3rd Kuban Cossack Cav. Regt. (Commander: Lt. Col. Jungschulz)

5th Don Cossacks Cav. Regt. (Commander: Lt. Col. Kononov)

6th Terek Cossacks Cav. Regt. (Commander: Major H-D von Kalben)

Of the six regimental commanders, Kononov was the only non-German. The two brigades were supported were supported by a reconnaissance company, two mounted artillery Abteilungen, a pioneer battalion, a supply column, and a medical section. Each of these had the number 55. For example, the first mentioned was:

Divisions-Aufklärungsabteilung 55

There was, in addition, a Volunteer Training and Replacement Regiment (Freiw. Lehr-und Ersatz-Regiment) under Col. von Bosse with its headquarters in Mochovo. This training and replacement regiment had some ten tot fifteen thousand men and boys, since it included a Young Cossacks School – a sort of Cadet Corps of Cossacks orphans between the ages of 14 and 18 who were, figuratively speaking, “adopted” by the division. There was also at Mochovo an Officers Training School.

On 1 June 1943, Pannwitz was promoted to Major-General and made Kommandeur aller Kosakenverbände (Commander of all Cossack Units). Not all the army’s Cossack units were incorporated into the new division; some continued to function independently. The division was without question the most thoroughly “Russianized” in the entire Wehrmacht. Its only all-German component was the Motorcycle Reconnaissance Section 55. The majority of the officers were Russian, and in the 5th Don Cossack Cav. Regt. entirely so. Most of the technical specialists were German, as were most of the senior commanders, but it was Pannwitz’ intention that as many of these posts as possible would eventually be taken over by Russians. Word of command was, throughout the division, Russian not German. Naturally interpreters had to be engaged since not all the German officers were conversant with the language.

The division boasted its own Trumpet Corps impressively mounted on white horses. There was also a general’s Konvoi (personal escort) to accompany Pannwitz on official excursions.

Each regiment consisted of six squadrons, subdivided into Gruppen of twelve horsemen apiece. There were, however, not quite enough horses to go round and about half of the members of the 2nd Siberian Cossack Cav. Regt. were mounted on bicycles! Each of the brigades had a “Heavy Squadron” equipped with eight 80mm mortars and eight heavy machine guns. There was a divisional antitank squadron with five 50mm antitank guns in addition to its light machine guns and mortars. The two mounted artillery Abteilungen (one Don, the other Kuban Cossack), had six batteries of field guns plus a Headquarters Battery (each battery of around 200 men and horses). At a later stage a howitzer battery was added.

All-in-all, the division could have been a formidable addition to Germany’s frontline strength, but during the course of its creation two significant developments had taken place. Firstly, the Red Army had passed over to the offensive and retaken the German-occupied Cossack lands, secondly, there had been a major shift in policy with regard to the deployment of Russian volunteer units. Hitler had ordained that they be removed from the East and sent either to France or the Balkans. Both these events had an injurious effect on the morale of the division. As the Germans withdrew from the Crimea and Kuban, thousands of Cossack families fled with them. A Cossack settlement was established at Novogrudok in Belorussia under Timofey I. Domanov as “Field Ataman.” At Novogrudok the Cossacks organised their own self-protection militia without waiting for German instructions to do so. When Novogrudok itself came under threat by the advancing Red Army, the Cossack families were allocated a new “home” at Tolmezzo in Northern Italy. A report by General V. Naumenko of October 1944 estimated the population of his home, or Stan, as being 15,590 men, women and children.

The division was not, as it had hoped, sent to fight the Red Army, but instead was ordered, in September 1943, to proceed to Yugoslavia and deal with the increasing vexation of Partisan activity in that part of the world. This order had a very adverse effect on the enthusiasm and zeal of the troops. What had the Partisans of Yugoslavia to do with the hoped for liberation of their homeland from the throes of Soviet Communism? General Pyotr N. Krasnov, ancient and venerated former leader of the Cossacks in their resistance to the Reds at the time of the Civil War, was asked to address reassuring words to the men and to hint that this was merely a “blooding” of the division in preparation for its return to the front line. After this patriotic allocation the division set off, via Czechoslovakia, to northern Yugoslavia. The Volunteer Training and Replacement Regiment, including the Young Cossack School, was removed to France.

The Cossack Cavalry Division took part in several major offensives against the Partisans including “Operation Rüsselsprung” (Knight’s Move), the attack on Tito’s headquarters in Bosnia from which the Partisan leader evaded capture only by the narrowest of margins. During the summer of 1944 the two brigades were upgrades to become the 1st and 2nd Cossack Cavalry Divisions. In November 1944 the S.S. announced its intention of taking over both and creating a larger formation to be known as the XVth Cossack Cavalry Corps. Pannwitz, although certainly no friend to the Nazis, did not try to resist, arguing that it was the only way to ensure a regular supply of modern arms and equipment for his troops. It was, in any case, the logical outcome of the fact that Himmler had come to regard the S.S. as natural custodian of all foreign volunteers in German service (no longer just those of “Nordic” origin). Also, the S.S. was responsible for the conduct of anti-guerrilla operations and it was on this task that the Cossacks need not adopt Waffen S.S. ranks or insignia and that S.S. officers would not be seconded to the Corps. He envisaged that the final strength would be three, not two, divisions. The projected 3rd Cossack Cavalry Division was to be based on von Renteln’s Cossack Regiment (currently designated Festungs Grenadier Rgt. 360), and was to include the Kalmuck Cavalry Corps. But the transaction remained largely theoretical. The 3rd Division was never activated. A similar hypothetical exercise was the supposed transfer of the entire corps to the army of the K.O.N.R. But as this was sanctioned by Himmler on 28 April 1945 (a week before the end of the war in Europe), it is hardly necessary to add that it never took place.

Not all Cossack units, even in the last days of the war, were incorporated into Pannwitz’s Corps. For example, in the Ukraine four Schuma battalions (Nos. 68, 72, 73 and 74), raised in the early months of 1944, were classed as Kosaken-Reiter-Front-Abteilungen (Cossack Mounted Frontline Companies). At the Cossack Stan in Northern Italy there were four Plastun regiments (two Don, one Terek, and one Kuban), as well as a cavalry formation of 962 men, a Reserve Regiment (376 men from various regions), and an Escort Squadron of 386 men. (All the forgoing as of October 1944.) Overall responsibility for the Cossacks in northern Italian settlement area rested with the Higher S.S. and Police Leader, Adriatic Coast, S.S. Gruppenführer Odilo Globocnik in Trieste.

Disclaimer: I do not support any of the views these people might have had, this is just for creative purposes and alt-history curiosity!

Credit to TheRanger1302 for his adaptation of the GLK base and Grand-Lobster-King for the original design.

Related content

Comments: 3

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 1

👍: 0 ⏩: 0