HOME | DD

Sorroxus — Endos

Sorroxus — Endos

#alien #alienplanet #alienworld #biome #biosphere #map #planet #speculative #worldmap #planetmap

Published: 2021-07-11 14:04:43 +0000 UTC; Views: 3762; Favourites: 21; Downloads: 4

Redirect to original

Description

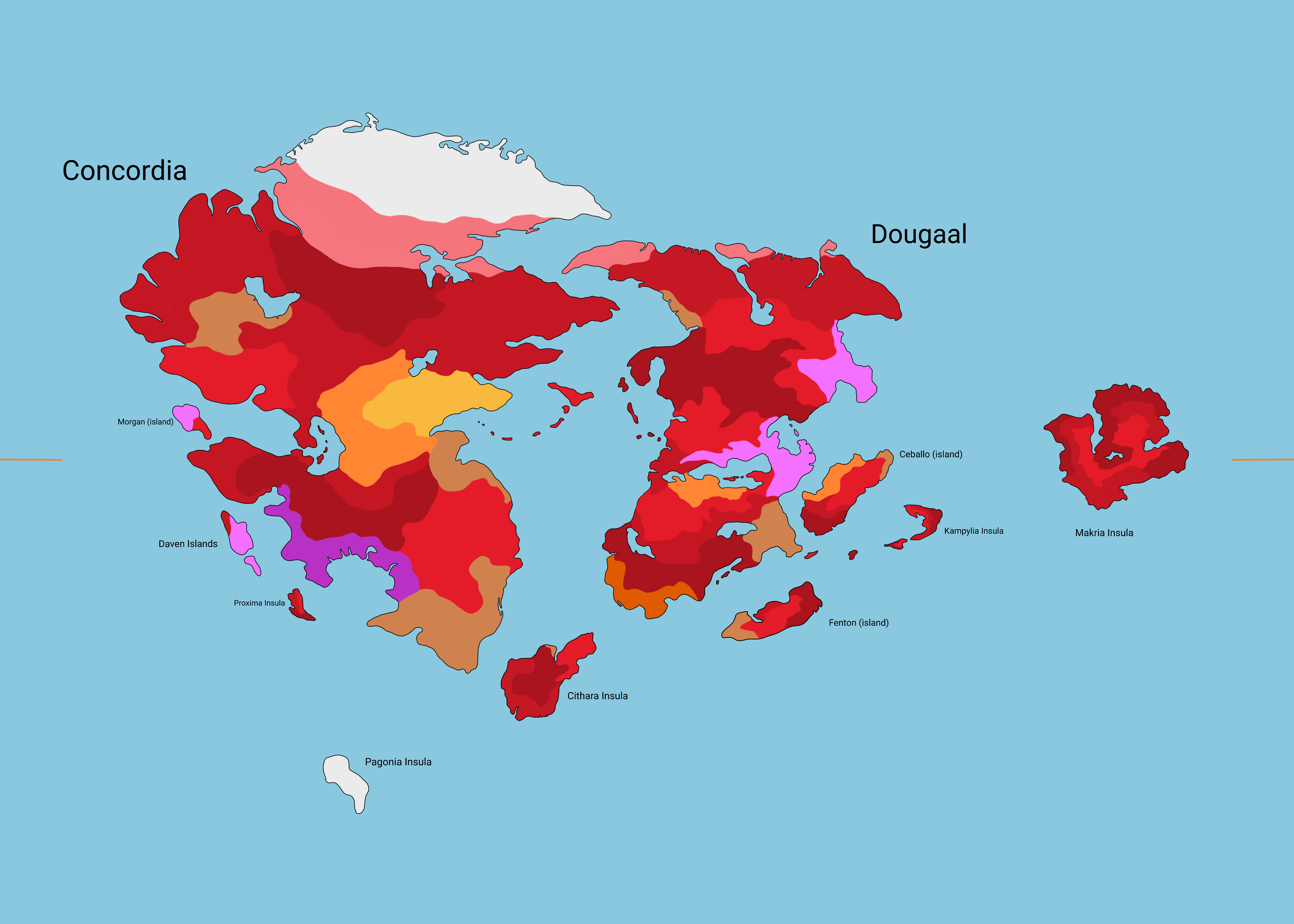

It’s about time I got around to making a map of Endos, the alien planet of the stithopods. This map is a geographical map, and depicts the natural world of Endos and its biomes. A table of colors correlated to their biomes is given below.

Bright Red = Steppe-Land

Pale Red: Tundra

Medium Red = Frag-Forest

Dark Red = Forest Land

White = Arctic Region

Light Orange = Savanna

Dark Orange = Rainforest

Yellow = Arid-Land

(Light) Purple) = Jellytree Forest

Tan/Brown = Clam-Bush Forest

Dark Purple = Jelly Steppe

And now I shall cover the biomes in more detailed descriptions…

Steppe-Land:

The Steppe-Land, or simply called the steppe, is one of the most common biomes of Endos, and is a biome made mostly of lampaphytes, which are common plant-forms made up of a small and spongy bulb that resides in the ground with tall, red leaf-like blades poking up from the ground. There are many groves of trees in the steppe, which provide shade and refuge for many stithopods during the hotter days of what would be considered "summer."

The biome is home to many clades of terrestrial stithopods. Such a biome is common amongst both the Concordian and Dougaalese continents, although more of Concordia’s land mass is made up of the steppe and the plentiful lampaphytes. While the non-anamalian biological components of the steppe are made up of the common lampaphyte and tentaclophyte (tentacle plant) (tree-like organisms), the terrain itself can vary from relatively flat land to mountainous terrain.

Tundra:

The Tundra is a cold, arid biome where few lifeforms live. Of those that do inhabit these cold regions, they are cold-adapted stithopods and cold-adapted plant life. Here, large creatures rule, as their larger bodies create more body heat.

The terrain of the Tundra can vary, with long stretches of flat land overshadowed by large mountain ranges.

Frag-Forest:

The Frag-Forest is a biome that, hence the name, is a forest-type biome that is punctuated by vast clearings of open land, often dominated by stegaphytes and taller lampaphytes. The Frag-Forest is a lot like a thick “traditional” forest, but, like mentioned before, is more punctuated and fragmented. This biome is more common than some other biomes, but is not as common as the steppe biome. However, the biome itself is extremely plentiful with diverse clades and microecologies, which owe their existence to the variability in the geography these biomes possess. While the steppe is home to a very plentiful amount of genetic diversity, the frag-forests are two-fold.

Similar to the steppe, the terrain of the Frag-Forests can vary, although most of the time the Frag-Forest terrain will either be flat or somewhat hilled, with little mountain terrain. If there are mountains, Frag-Forests will merge into thick forests.

Forest Land:

The Forest Land, or simply the forest, is a biome that, I do not think, needs any type of detailed introduction or description. This biome is pretty much the same as the forests of Earth, and like on Earth, the forest biome is relatively common and home to a good bank of genetic diversity.

The terrain of the forest can vary widely from hilled, flat, mountainous or even extremely mountainous, in which mountain ranges are extreme and steep. In these extreme mountain terrains, life has adapted to be extremely nimble.

Arctic Tundra:

The Arctic Tundra is a biome of Endos similar to the Terran tundra, and while they cover a fairly extensive amount of the upper-norhtern Concordian and some of the upper-northern Dougaalese continents, and the small southern Pagonia Insula, the genetic diversity within the bounds of the biomes are low, with the harsh tundra bearing little to offer for the diversity of plant life, which has observable effects on the stithopods that inhabit. The scarcity of food, which becomes more of a problem the more north one travels, causes stithopods to have average sizes of less than five feet at a maximum, and most genera of tundra stithopods living in the tundra typically only has one representative (species.)

The Arctic Tundra’s terrain is, like its ecology, very bare and unremarkable, with flat plots of snow-covered land being pretty much the only terrain there is. Sometimes there are mountainous terrains, though these terrains often occur at the edges of the continent, and don’t occur more inland.

Savanna:

The Savanna biome is a biome similar to the tundra, and the ecology of the Endonese savanna reflects the savannas of Earth in many ways, from the arid landscape to the lifeforms well-adapted to the hot climate. The savanna of Endos is a biome with less commonality globally, and only exists in Concordia and Cithara Insula, although most of the Endonese savanna is localized in the Concordian continent.

Similar to the tundra, the lifeforms of the savanna yield less genetic diversity than the steppe or forests, although the savanna is slightly more plentiful in resources than the tundra, and so has somewhat more genetic diversity. As well, the savanna’s terrain is made up primarily of, once again, flat plots of land, however there are the occasional plateau and mountain.

Rainforest:

The Rainforest is a biome that, while having less global ground, is the most diverse biome in the entire planet, with the biome being home to a bounty of species and clades. The biome itself occupies the southern-lands of Dougaal and the eastern Cithara Insula, and both of these biomes, while fundamentally alike, are home to vastly different representatives one may think they were two different biomes altogether.

Unlike many of the biomes of Endos, with some exceptions, the terrain of the rainforest is extremely mountainous and textured, with some of the most extreme and highest mountains being found in the rainforest. This incredibly varied and inconsistent terrain, coupled with the wonderfully varied ecology, has allowed for some of the most diverse forms on the planet, although that’s already been mentioned.

Arid-Land

The Arid-Land is a biome similar to the desert, and has the least genetic diversity of all biomes. The biome can only be found in the Concordian east coast, and is the least common biome by dispersion, yet is not the least common biome by landmass. There is not much to say about this biome, as it is a pretty bare biome, but it is worth mentioning that the main sub-biome of the Arid-Lands is of hot and blistering stone, with sand being uncommon beyond beaches. In the Arid-Lands, there are few sand pockets, and most of the biome is of stone, which has led to some divergences in the body-plans of stithopods compared to the desert-adapted tetrapods of Earth.

The terrain of the arid land is a lot like that of the Grand Canyon of Earth, with vast expanses of eroded mountain terrain, which, like the more mountainous terrains on the planet, has allowed for relatively diverse lineages, although because of the inherent dryness and aridness of the Arid-Lands, this diversity is less so than many other places.

Jellytree Forest:

The Jellytree Forest is a diverse biome completely unique to Endos, and was one of the first biomes to be encountered by the 1st Expedition Squad, and made an impactful first impression on the scientists. The Jellytree Forest is unlike anything we have here on Earth. To understand this biome, it would be best to understand the staple-flora of the biome—the Jellytree. The Jellytree, scientifically called the “piktiphyte” (jelly plant), is a type of tree-like plant that has a rather sausage-like appearance, with a thick base tapering a little as the gaze rides up the trunk. At the top of the trunk are long stalks lined with palm tree-like leaves. The Jellytree itself gets its name from the composition of the plant itself. The “tree” has a soft, almost leathery flesh-like exterior, and when the flesh-bark is broken, one can find a gooey jello-like “trunk,” which is easily able to be torn apart, but keeps its shape with an internal bone-like shaft, as well as the leathery exterior.

This is the defining trait of the Jellytree Forest (the Jellytree itself), and many scientists hypothesize the most basal forms had their beginnings in the Dougaalese continent, and, through the forming and breaking land bridges, made their way to Concordia, although none are found on the continental Concordia, and are instead most common on the islands.

Because of this unique biome, many stithopods have adapted in extremely odd and wonderfully imaginative ways, and some forms have even evolved to feed on the squishy insides of the Jellytrees, while others have evolved to suck on the internal liquids instead.

The terrain of the Jellytree Forests can consist mainly of steppe-like plains or Frag-Forest-like stands of Jellytrees, although some instances of savanna-like Jellytree Forests have been recorded. Like mentioned before, the inhabitant of the Jellytree Forests are plenty diverse in nature, yet the varied sub-biomes of this general biome has resulted in extremely specific clades of stithopods, each seemingly unique to that specific sub-biome alone, which has presented great wonder and excitement, but has also been the bane of astrobiologists who seek to categorize as many varieties as they can.

Clam-Bush Forest

The Clam-Bush Forest is another biome completely unique to Endos, and as such the genetic diversity of the plant life and animal life has adapted into radiations not found anywhere on Earth, and even on Endos they are pretty unique. The main constituent of the biome are the so-called “clam-bushes,” called “placophyte,” which means “plated plant.” Although, somewhat misleadingly, the actual term of “plant” is not an accurate description of the clam-bush. While the first scientists had initially categorized it as a type of plant, further research has proved the clam-bush is actually a sessile animal, similar to bivalves on Earth, so the scientific name is technically inaccurate, yet the name has stuck as it was commonly used to the point where it was able to resist the push for a more scientifically accurate name.

The term “clam-bush” is actually a general umbrella term for the numerous species of sessile animal organisms that feature the basic body plan of a soft, squishy meaty body protected by large external bone-like shells, and is not in reference to any specific species, though colloquially the term is used most in reference to the most common type of clam-bush, a tall four-foot tall organism that covers most of the clam-bush forests. The tallest clam-bushes can grow to about ten feet in height, and the shortest can reach about six inches.

Because of the nature of the clam-bush (the hard bone-like shell), the stithopods that inhabit the clam-bush forests have, in much a similar manner to the inhabitants of the Jellytree forests, have evolved special adaptations to help them break the shells and get to the meaty insides. The most common biological tool employed by the numerous species that feed on the clam-bush is a hard club-like structure derived from the trunk—the tip of the trunk has evolved growths of osteoderm-like bumps, which have fused into a hard bone-like sheath.

The terrain of the biome, which is consisted of many sub-biomes, are most often steppe-like plains, forest-like stands of clam-bushes and marsh and bog-like wetlands of clam-bush. However, the most common type of terrain is the steppe-like plain, although none of the other terrains mentioned should be overlooked.

Jelly Steppe

The Jelly Steppe is the third biome completely unique to Endos. The presence of not one, not two but three completely unique biomes and ecologies on Endos has filled our scientists with much excitement and awe, and field studies have been rampant throughout these three biomes. However, the focus is not on the excitement this has stirred up, so I digress.

The Jelly Steppe biome, much like the previous two endemic Endonese biomes, is a biome unique to Endos and not found anywhere on Earth, and in fact is specific to Concordia, so the life found there has evolved in its own way to be the most optimal it can be. The sole defining trait of the Jelly Steppe is the presence of a vast and far-reaching plain of jelly-like “steppe-land.” Studies have shown the Jelly Steppe's gelatin is made up of many trillions of small, compacted amoeba-like organisms, and is therefore a living biome. The Jelly Steppe has a leather-like skin, and beneath that is the fleshy, water-rich "flesh" that many inhabitants of the Jelly Steppe have evolved to feed on.

The biome itself may be alive, but no instances of the Jelly Steppe actively devouring whoever steps onto it has been recorded, though that doesn’t mean it hasn’t happened. Instead, the Jelly Steppe appears to be completely defenseless against anything that chooses to eat it, and there are a lot of creatures specially adapted to feed on the Jelly Steppe.

In addition to feeders, the Jelly Steppe is home to creatures who choose to bore into it, and many creatures have specialized fusiform snake-like bodies to help them tunnel through the Jelly Steppe, and some larger organisms have evolved long, needle-like trunks to pluck them out. This truly is quite fascinating, especially by Endos’ standards.

While it may seem the rampant tunneling and feeding that the Jelly Steppe endures would wear down the biome and soon drive it to a far smaller plot of land, the Jelly Steppe’s amoebic constituents constantly split apart into two, and this happens so fast and constantly the Jelly Steppe has maintained its shape for millions of years, we have concluded.

Despite being home to a great wealth of animal life, though plant life oddly seems to be missing, the biome itself, which, like the previous two, acts as a general term, is not home to a particularly varied terrain, and the Jelly Steppe mostly inhabits flat lands, and rarely inhabits anything more varied than small hilly plains.

Anyway, this wraps up this description, bye bye : ) …