HOME | DD

Sorroxus — The Chase (old/outdated)

Sorroxus — The Chase (old/outdated)

#alien #aliencreature #aliendesign #biology #creature #interaction #speculative #traditionalart #specbio #specevo #exobio #stithopod

Published: 2021-09-29 11:48:16 +0000 UTC; Views: 4194; Favourites: 34; Downloads: 2

Redirect to original

Description

Before we start, I wanna say that I actually got this done the day I started it, but I put off posting it for so long because I could not, for the life of me, get a good picture. In fact this picture is pretty bad, but it was the best I could get, and I mean that. I also was lazy and didn’t write the description until a few days after I finished it, the drawing. But I digress. I got it done, so here it is.

(also the stiletodactyl depicted here is slightly outdated)

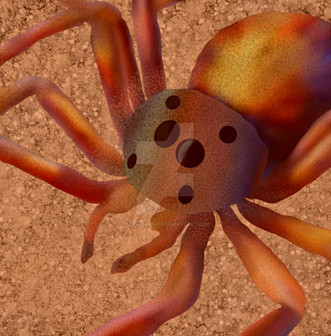

Here we see an occasional but fascinating sight in the savanna-land of Cithara Insula. A savanna-dwelling stiletodactyl (stiletonycha lophos (crested dagger-claw)) chasing a savanna-adapted theropteran dyoparoteran (teneusouranokynigis lenoni (Lenon’s thin sky-hunter)).

The Stiletonycha Lophos is a small, savanna-adapted stiletodactyl of around 4 feet in height, weighing anywhere from 300-340 lbs in weight. It has evolved to inhibit the niche of small savanna-adapted mesocarnivores, and regularly subsist on both carrion, fresh meat and sometimes savanna-adapted lampaphytes.

The S. Lophos is a very social creature, living in packs of five to eight, often traveling in packs to take down larger prey, though when they are hunting smaller prey, it is often one or two that will give chase. In this image, a lone S. Lophos has spotted a theropteran dyoparoteran, and has given chase. While he may not know it, the fact that he won’t be able to catch this flying prey, that does not deter him, and so he insists on giving chase.

While the Stiletonycha Lophos does not tend to hunt flying prey, this theropteran dyoparoteran was resting prior, and the S. Lophos depicted here was in the process of sneaking up behind it, only to spook it and ruin its chances of killing the theropteran dyoparoteran.

The S. Lophos is a generalist carnivore, and tends to eat much of what’s around, so long as its gut can handle it. It’s not highly specialized to fit any niche, and more or less bounces between roles that are already occupied by more specialized creatures. This constant bouncing, though, does not encourage niche partitioning, as none of the more adapted creatures are competing much with the S. Lophos.

The next creature we see is the theropteran, which is a member of the dyoparoptera class (two pairs of wings), a class of flyers descended from oceanic organisms that would leap out of the water and glide on their fins for a short period of time. This clade of oceanic gliders eventually evolved powered flight, and they soon spread all over the world and occupied all manner of aerial niches they could get their hands on, even giant aerial filter-feeding niches. One thing worth noting is that, while the dyoparopterans have two pairs of wings, the work of actually flying itself is carried out by the larger pair of wings situated toward the back of the body. The smaller anterior pair of wings aid in altitude and speed, being able to fold back or forward and turned up or down. The tail, which bears a pair of fins, aids in actual direction, and the flexing of the tail can, in tandem with the canards (anterior wings), change flight direction.

This one here is on the smaller spectrum of the theroptera family, belonging to the genus Securisoptera (axe-wig), which occupy the niches of small aerial predators that hunt after small little creatures, such as savanna-adapted zitonbrachids. Just as a note, the largest theropteran species is the Megalolepidoptera Rex (king giant knife-wing). But regardless, the wingspan of the one depicted above is around six feet.

The whole dyoparoptera class exhibits sequential hermaphroditism, as opposed to the stithopods’ simultaneous hermaphroditism. Specifically, the dyoparopterans are protandrous, which means they begin life as a male, but can switch to become female if need be, such as if there’s a shortage of females.

Reproduction for the dyoparopterans is sexual, with males fertilizing females and females carrying the baby inside her.

As mentioned earlier, such scenarios are rare, but when they do happen, they’re quite entertaining.