HOME | DD

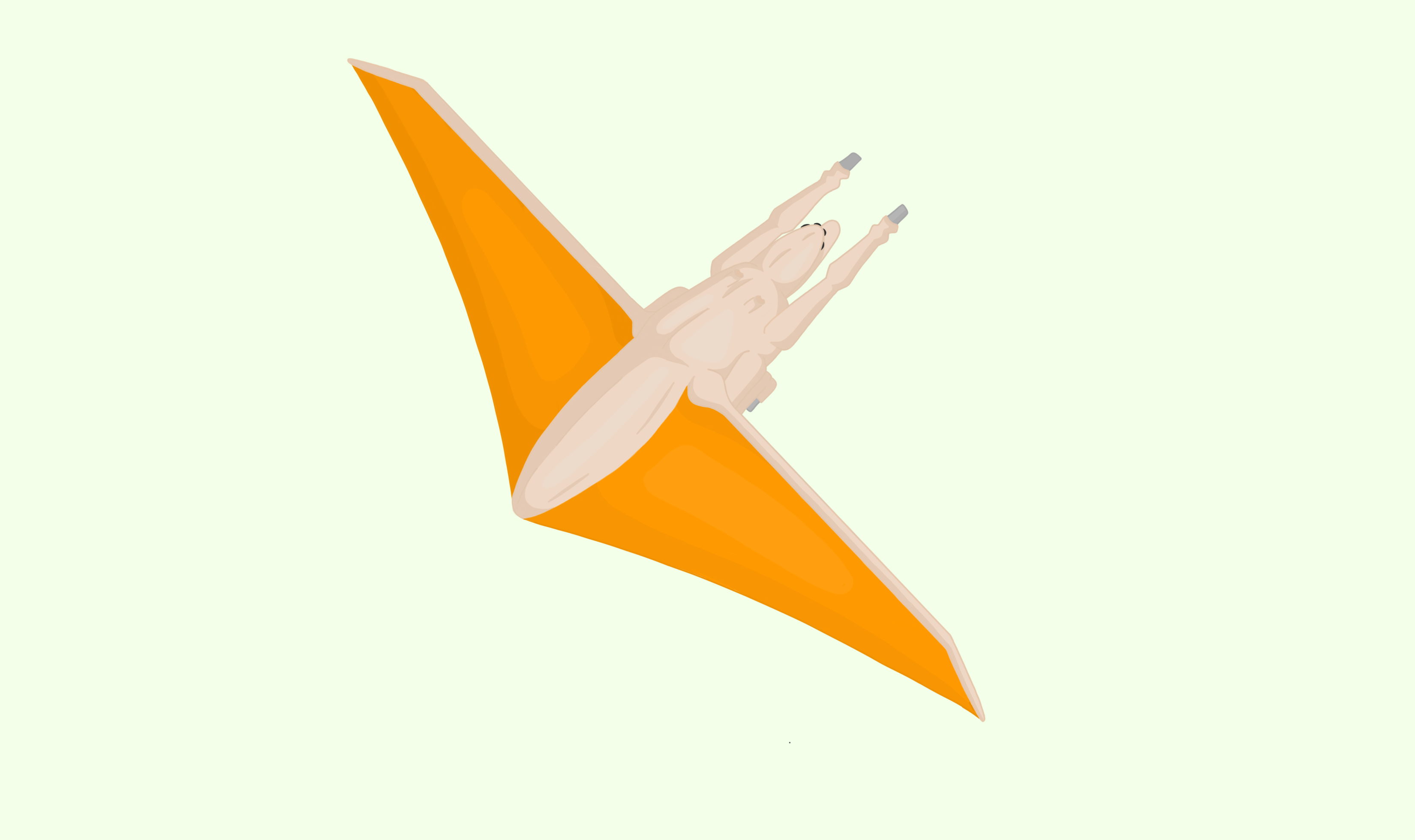

Sorroxus — Xenopteran In Flight

Sorroxus — Xenopteran In Flight

#alien #creature #creaturedesign #specbio #specevo #aliencreature #aliendesign

Published: 2022-08-28 12:26:51 +0000 UTC; Views: 1258; Favourites: 13; Downloads: 3

Redirect to original

Description

The planet of Endos is vast and expansive, as a basic look at a map would have one believe. The planet is 12% larger than Earth, its continents are larger and the oceans are equally larger. Even after having settled communities of scientists all over the planet, we still have yet to not only catalog every species, but also explore every corner of the planet. And yet, despite how large this planet is, the stithopods have come to dominate it. From the waters to the land, even to the air, no other clade can rival their dominion. No other clade, in my opinion, best exemplifies the dominance of the stithopods better than the Xenopterans.

The clade Xenoptera (strange wing) is an order of Monocardian stithopod. Monocardians are one of the two classes of stithopod, the other being the Dyocardians. But regardless, the Monocardians were the first clade of stithopod to evolve powered flight, with the Dyocardians having not evolved powered flight, perhaps because most aerial niches are already filled by the Monocardian Xenopterans, leaving little room for other large fliers.

Xenpterans are the dominant clade of fliers on Endos, overshadowing the small, relatively unremarkable flying polypods. Being the dominant fliers, the Xenopterans have filled many different niches where they can, with many evolving to hunt land prey, aerial prey and oceanic prey, while others have evolved to feed on fruit, corpses and lamaphytes, though lampaphyte-eating Xenopterans are incredibly rare, as the lampaphytes don’t yield the great amount of energy needed for an activity like flying.

Xenopterans are a highly diverse order, and it should come as no surprise that many Xenopterans vary in size. The smallest Xenopteran has a wingspan about a foot in length, while the largest Xenopteran possesses a wingspan of around three hundred feet. Not only that, but the shape of the Xenopterans’ wings also varies, with some having short elliptical wings, while others have evolved pointed high-speed wings, while others have evolved soaring wings. The wings of Xenopterans are not made of feathers, and are instead made of membranous skin similar to bats or pterosaurs on Earth.

The exact reason why the Xenopterans evolved flight is not entirely understood, but we do have enough fossils to paint a picture of how it probably happened. We hypothesize that the earliest Xenopteran ancestor was a small arboreal creature, living up in the trees like squirrels or monkeys. We hypothesize that it would leap from branch to branch, and as time went on, it began to evolve a small gliding patagium stretched between their third pair of legs and their abdomen. Evolving this patagium further, the arboreal Monocardian species split into two lineages, the first of which kept its gliding patagium as just that, while the other lineage further evolved their patagium. As this lineage in particular continued to evolve, their patagium grew larger, their gliding legs got longer, and in a matter of a few million years, these odd little creatures gained the ability to fly, their rear wings evolving further to better aid them in flight. As they took to the sky, they faced competition from the already-established flying polypods. However, the polypods have no bones, and are squishy beings, which restricted their size. The flying Xenopterans, on the other hand, with their full, robust skeleton, allowing them to grow larger than their competition, soon surpassed the flying polypods. From that point on, the Xenopterans quickly spread all over the world in only a few hundred years, and they never looked back.

Being flying creatures, Xenopterans require powerful muscles to power their wings. Somewhat interestingly, whereas Earth vertebrate fliers rely on their powerful forelimbs for flight, it is the third pair of legs the Xenopterans rely on for flight, giving the flier an odd rear-winged design. This is because the most powerful muscles are located in the back, a trait common to all stithopods, so it only makes sense, then, that the wings would be in the rear.

When flying, Xenopterans will often stick their anterior limbs out in front of them in a “superman pose.” Their middle pair of legs are tucked close to the body and are folded up to prevent as much drag as possible. In flight, the trunk will also be tucked away to reduce drag, being coiled up under the head.

When on land with their wings folded up, they will locomote on their first and second pair of legs. When locomoting on land, the middle pair of legs takes on the role of the hind limbs, and will stretch back a little, giving the creature an odd appearance when walking about.

To get themselves back up into the air while they’re on the ground, they will bound forth in a quick running start, throwing themselves into the air and unfurling their wings. Once airborne, they will quickly flap their wings until they’re at a suitable altitude, in which most will begin to glide on the winds, conserving energy. This is most present in carnivorous forms, who spend a great deal of their time soaring in the air looking for a meal.

The Xenopteran seen here is a member of the genus “theroptera” (beast wing), and is the second largest of its genus. Named “Aerovenator Tachyopteryx” (fast-winged sky-hunter), it is a savanna-dwelling Xenopteran, and soars the high skies on its ten-foot wingspan looking for small critters to eat, such as small Monocardians like the savanna-adapted Zitonbrachids. When it has locked onto a potential prey item, it will fold its wings up and will plummet down at high speeds toward its target like a spear. Oftentimes, its prey will see it coming and will run as fast as it can. Unfortunately, the little legs of the Zitonbrachids the A. Tachyopteryx feeds on can only carry it around nine to twelve miles an hour, while the A. Tachyopteryx can reach a top speed of around sixty miles an hour when flying. As the A. Tachyopteryx gets closer to its prey, it will deploy its wings and will quickly dart at the creature, snatching it up with its legs, ascending as quickly as it can into the sky until it finally reaches a preferable altitude. Once it has reached said preferable altitude, it will drop its prey, letting it fall hundreds of feet to its death. Following the prey as it falls, the A. Tachyopteryx will safely land close to the now-dead critter and will begin to feast on it. To help it feed, its trunk has evolved a row of teeth on both of the fleshy jaws common to all Monocardians, the Dyocardians having trunks terminating in either a beak or boned jaws. But regardless, these rasping teeth help to rip off chunks of flesh, which it will pass into its mouth.

The Xenopterans are a true testament to the stithopods’ dominance over Endos, with their flight allowing them to take over the world in record time.